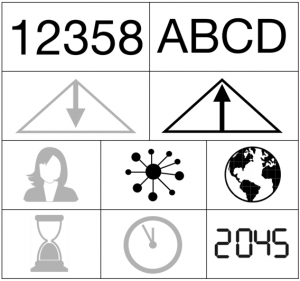

Visioning & Backcasting

Quantitative - Qualitative

Deductive - Inductive

Individual - System - Global

Past - Present - Future

In short: In a Visioning process, one or more desirable future states are developed in a panel of scientific and non-scientific stakeholders. In the process of Backcasting, potential pathways and necessary policies or measures to achieve these future states are developed.

Contents

Background

Visioning and Backcasting are historically connected and each of them cannot be thought without the other. Backcasting emerged earlier than Visioning during the 1970s and first in the field of energy planning, "(...) growing out of discontent with regular energy forecasting that was based on trend extrapolation, an assumed ongoing increase in the energy demand and a disregard for renewable energy technologies and energy conservation" (Vergragt & Quist 2011, p.748). Subsequently, Backcasting was furthered in this field in the USA, Canada and Sweden (1, 8). The topics approached through Backcasting shifted towards the field of sustainability after the "Our Common Future" report in 1987 (8).

Modern Visioning approaches emerged later during the 1980s and 1990s with the incorporation of System Thinking and participatory engagement (1). Since its emergence and due to a rising role of participatory approaches, different versions of Visioning have been developed, including future workshops, community visioning, sustainability solution spaces, future search conference, visioneering and others (1).

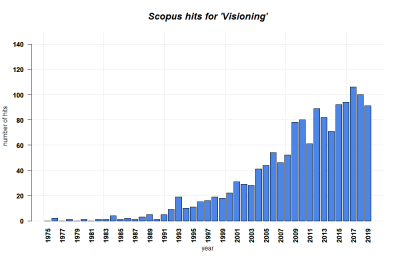

Today, Visioning is used most prominently within planning and planning research where it helps guide investments, politics and action programs (1). Examples for this are energy planning or urban planning (2, 3, 5, 7). It has also become particularly important in transformational sustainability science that tries to directly contribute to real-world sustainability transitions (1). In this field, especially the research body on transition management argues for a combination of social and technological innovation and multi-stakeholder-approaches for sustainable development (3). Still, Visioning research is still at a "nascent stage" (Iwaniec & Wiek 2014, p.544), and has not yet fully been established as a method.

What the method does

In a Visioning process, multidisciplinary stakeholders (most commonly scientific and non-scientific experts on the topic, or also non-experts in participatory approaches) are brought together for a workshop to collect ideas and finally formulate a joint vision as an answer to a previously asked question (1, 8). A vision provides “a key reference point for developing strategies to transition from the current state to a desirable future state, actively avoiding undesirable developments” (Wiek & Iwaniec 2014, p.498). This vision can take the form of qualitative or quantitative goals and targets (1). For example, such a vision could be a society based entirely on renewable resources or a technological process that causes minimum environmental impact (2). In theory, a vision can cover every spatial and temporal scale. Visions for the planet in hundreds of years are just as conceivable as a vision for a small company in five years. The exact dimensions depend on the intended goal of the Visioning process. The vision itself may exist on a very basic level, e.g. 'a world without hunger'. However, by adding more specific qualitative and especially quantitative targets and elements, the vision may become more complex. This complicates the subsequent Backcasting process which, based on a systemic perspective, needs to consider various societal and technological elements that influence the intended process of policy-making (2, 6).

Visioning combines data gathering, data analysis & interpretation: In preparation, sound knowledge of the issues at hand is mandatory which may be developed by analyzing and interpreting existent data on the current state of a particular system (e.g. a country, a company, a landscape) (3, 6). Based on this, a vision for said system is created, generating new qualitative and/or quantitative data. This process can be structured in four steps according to Wiek & Iwaniec (2014, p.504).

- Framing the Visioning process

- Creating initial vision material (vision pool)

- Decomposing and analyzing this material, and finally

- Revising and recomposing the vision

The Visioning process should continuously be reflected upon and revised iteratively (1).

A wide range of possible techniques and settings for vision development is available (6). Among these are abstract forms (vision maps, solution spaces), more realistic visualisations of landscape and city visions using GIS or video techniques; and a set of other visual and digital solutions (decision theaters, digital workshops) (1). More generally, ideas may be collected using e.g. Design Thinking approaches or brainstorming, and sorted through clustering and rating procedures, among others (3). Discussions and thoughts may be secured in form of notes, drawings or voice recordings (5). As per setting, a 'neutral' location (i.e. unaffiliated to specific stakeholders) may be preferable in order not to influence the Visioning process (3). Virtual solutions are possible - bringing people together physically, however, may provide benefits to their interaction that virtual solutions lack (3).

Complementary to the Visioning approach, Backcasting describes the process of developing pathways to reach the vision. While it is thus a method in its own right and not to be understood synonymously with Visioning, these two processes are directly connected to each other.

An example of Visioning and Backcasting

The '1.5°C' goal that was developed at the 2015 COP is a good example of a vision. It is both qualitative (with regards to the connection between humanity and nature) and quantitative (carbon emissions being at net zero). It may not be entirely realistic or probable, but it serves as a benchmark to be achieved. It was developed in close cooperation between policy actors and academia and implicates transformational political, economic and societal action. The latter is done in form of development pathways that can be seen as a result of the subsequent Backcasting process.

Strenghts & Challenges

Visioning and Backcasting are approaches to thinking about the future, and are to this end comparable to Scenario Planning (the development of possible futures) and Forecasting (the extrapolation of probable future states). However, Visioning and Backcasting provide advantages - and disadvantages - over these methods:

- Scenario Planning as well as Forecasting are based on the idea of extrapolating current trends to imagine potential or likely futures. This may be seen as rather unlikely to spur holistic societal change, since it accepts the given trajectories instead of thoroughly questioning them (3, 6). Backcasting that is based on a vision, however, works with desirable futures (visions) and develops policies that ought to lead there. Due to this normative premise (see Normativity), it allows for a stronger connection between the envisioned future and conceivable policy measures (2, 6). Backcasting "permits a better feel for the effects of different policies" and "reduces the tendency (...) for the results of an analysis to be rendered instantly obsolete by the response to it" (Robinson 1982, p.338). A vision may provide insights into "(...) associated uncertainties, different perspectives, range of options and strategies to move forward" (5, p.1922).

- Backcasting may be the preferable approach when the issue at hand is very complex and influenced by external forces, current trends are part of the problem, major change is needed and the time horizon involved is long enough to allow for considerable deliberate choice. This illustrates the difference between Scenario Planning and Visioning as different approaches to thinking about the future (6).

- Additionally, insights from psychology indicate that positive, inspirational visions have a stronger motivational impact than a "what-we-should-be-doing" (1, p.498) set of push factors, as they may arise during more traditional planning approaches.

- Aside from the created vision, Visioning can offer further benefits: “(...) [P]articipatory visioning activities fulfill several process-level functions, including building capacity, empowering stakeholders, creating ownership, and developing accountability.” (Wiek & Iwaniec 2014, p.498) It can bring together actors who have never before spoken to each other. A successful Visioning process may thus also be measured based on "(...) how it subsequently affects the participants' minds and behavior" (Davies et al. 2012, p.57). It is presumed that even values and convictions may be altered during the process (3).

Normativity

Connectedness

Visioning is connected to various other methodological approaches.

- First, it is based on a System Thinking approach, recognizing the interconnectedness and causal interference of elements within a system.

- Visioning and Backcasting processes may take place in a Living Labs & Real World Laboratories environment.

- In preparation to the Visioning process, a Content Analysis, Interviews, Ethnographic Observations, Surveys, Problem Mapping, Supply Chain Analyses, among other approaches, may be undertaken to better understand the current state of the examined system and its prevalent issues (3, 7).

- A Stakeholder Analysis may be conducted to identify relevant individuals and actors for the Visioning process.

- As mentioned before, Visioning processes are commonly combined with a Backcasting process during which the strategies and pathways are developed that are necessary to reach the goals and targets included in the vision. Sometimes, the line between mere Visioning and the development of strategies by Backcasting fades, leading to explicit strategies being developed as a part of the Visioning process (see e.g. (7)).

- Also, a Visioning process may be followed by Scenario Planning: after envisioning what is desirable, stakeholders may think about what is actually realistic (5).

- The envisioned futures may be reviewed by further means. If the vision includes quantitative goals for a product, they may be examined using a Life Cycle Analysis. The visions may also further be verified by Interviews with relevant individuals whose feedback is further taken into consideration. Serious Gaming approaches and Simulation Games, Thought Experiments as well as System Models are conceivable approaches to simulate them and identify potential flaws. This variety highlights the fact that visions are foremost constructs that need to be further implemented in methodological designs to lead to practice-oriented solutions.

- If desired, the impact that the Visioning process had on the actors involved may be assessed by subsequently conducting Interviews (3).

Everything normative about this method

Visioning is normative from its core - it revolves around thinking about desirable futures (1, 2, 8). What is desirable is a question of cultural, societal and political negotiation (4). This is further complicated by the fact that, in order to create a vision that is shared by and respects all relevant actors, the Visioning process should be participatory and open towards diverse stakeholders' perspectives (1). The question of what is desirable is therefore a very complex one. For more thoughts on the role of normativity in transdisciplinary methods, see the entry on Transdisciplinarity.

The idea of a vision of a desirable future has been criticized in academia as being too impractical and unrealistic (1, 3, 4). However, this difference to probable scenarios may be seen as an advantage, spurring creativity and opening up mindsets (6). It has therefore been claimed that “visions ought to be idealistic, free, open, innovative, and, in fact, not (too) realistic” (Wiek & Iwaniec 2014, p.498). At the same time, they should be internally coherent, plausible and motivational in order to serve as helpful guidance for policy-making (1, 6).

Outlook

Due to the method's novelty, there is a lack of sound theoretical base and methodology. Visioning is still in its “nascent stage” (Wiek & Iwaniec 2014, p.509) and there needs to be more agreement on its methodological elements. This development of the method may best be furthered in close collaboration between academia and practice (1).

It can however be stated that Visioning and Backcasting may provide essential benefits for Sustainability research in the future. Sustainability Science has been framed to aim for System, Target and Transformation Knowledge and targets real-world problems and their solutions in integrated, participatory modes (see Brandt et al. 2013. A review of transdisciplinary research in sustainability science). To this end, a Visioning process builds on system knowledge, and aims for target knowledge, while Backcasting provides transformation knowledge, all in transdisciplinary environments.

An exemplary study

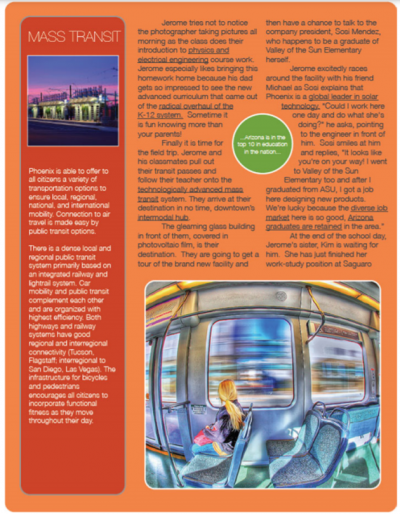

In their 2014 study, Iwaniec & Wiek present the process and results of a case study from Phoenix, Arizona, USA. Here, the City's Planning Manager approached Arizona State University, which resulted in new planning framework for sustainable urban planning and related educational outcomes. Part of this collaboration was a Visioning workshop, in which a sustainability vision for Phoenix in 2050 was set to be developed with public participation, and later be incorporated in the city's planning processes.

The Visioning process followed six stages (p.546):

1) Framing the process

In the first step, the temporal, spatial, methodological and thematical scope of the visioning process was determined by the legislative requirements and demands of the City of Phoenix Planning Department. They wanted to focus on the pillars Environment, Community, Economy and Infrastructure as well as the year 2050, decided for public participation in the process, and the visioning procedure was intended to become a new paradigm of sustainability-oriented city planning.

2) Creating visiong statements and priorities

In 30 small participatory meetings (two in every of the 15 city villages of Phoenix), 13-40 individuals each were introduced to the visioning process, and asked for vision statements, i.e. answers to the question "Imagine Phoenix as the best it can be in 2050 - What do you see?". The created statements (759 unique statements across the meetings) were prioritized in a voting activity, which resulted in 15 lists of prioritized vision statements.

3) Analyzing the vision drafts

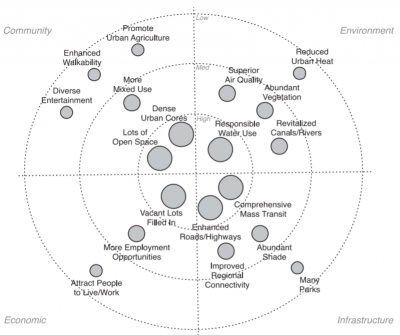

In the next step, Content Analysis was used to deconstruct all vision statements into a standardized element (what should be there in 2050?) and a value proposition (how should it be?) each, which additional descriptive codes "to specify actors' role, impact, location and spatial scale." (p.548). All identified 'vision elements' (1717 in total) then were analyzed using System Analysis, Cluster Analysis, Network Analysis and further statistical measures. This was done to assess for each village how the elements relate to each other, if there are missing elements, and if elements are contradictory, as well as across the villages to compare the different visions and to see how consistent the overall city vision was. In the end, topical subsystems for the city were extracted, and an initial narrative for the city vision was created based on the results, which was visualized in form of maps for each village and the whole city. The process in step 3 was iterative and a cooperation of the city planners and the researchers.

4) Reviewing and revising the drafts

The fourth phase consisted of a workshop, to which all participants of the 30 smaller meetings were invited, and additional citizens, with a focus on inclusive participation (Hispanic, youth). In a plenary session, all participants were introduced to the results of steps 2-3, i.e. the preliminary vision in form of maps, visuals and a narrative. Then, everyone was distributed into 12 groups of 9-10 participants, with two groups working on one of six urban subsystems each. These subsystems were: Open Governance, Enhanced Roads/ Highways, Responsible Water use, Comprehensive Mass Transit, Lots of Open Space, Dense Urban Cores, Abundant Vegetation. For each subsystem, vision elements were physically presented to the group on gameboards, with replaceable arrows indicating relationships between these elements.

Then, each participant was asked to illustrate all vision elements, and the group created a collage and narrative for their respective subsystem. The physical systemic representation of the subsystem was discussed and adjusted by the group, and vision elements were reprioritized. The new version of the subsystem vision was again discussed, also in terms of its sustainability concerning resources, environmental impact, and social justice. In the end, a concluding narrative for the subsystem was developed.

In the final plenum, all subsystem narratives were presented, leading to a range of results for the whole city visioning: "illustrative collages, various photo-documented game-board configurations and descriptions and the final narrations of the visions." (p550). Post-workshop feedback was also gathered.

5) Finalizing the vision

Now that the initial vision elements (Step 2) and the results of their systemic analysis (Step 3) were revised (Step 4), the "revised vision subsystems were reintegrated into a new system map of the city vision." (p.550) All visioning results so far were compiled and analyzed again, and a final report was created that "represented the vision for Phoenix 2050 as a systemic, coherent and sustainable city vision." (p.551). The main results of this report found their way into the city's planning documents.

6) Final review and dissemination

The plan for the final step in this case study was to have the public vote for or against the document which the newly created vision had become a part of. However, due to political reasons, in the end another visioning process was started which built on the results of the presented first process. However, as the researchers highlight, this is in line with the iterative and adaptive underlying visioning methodology. Also, they state that the presented visioning process already helped build capacity in terms of visioning both for the planners and the public, as suggested by a post-workshop survey.

Key Publications

Theoretical

- Robinson, J.B. 1982. Energy backcasting: A proposed method of policy analysis. Energy Policy 10(4). 337-344.

Explains the Backcasting process and the role of a vision in this process.

- Constanza, R. 2000. Visions of alternative (unpredictable) futures and their use in policy analysis. Conservation Ecology 4(1).

Illustrates four visions for the year 2100 and outlines how one might choose from these.

- Wiek, A. Iwaniec, D.M. 2014. Quality criteria for visions and visioning in sustainability science. Sustainability Science 9. 497–512.

Present ten quality criteria and a set of tools and techniques for Visioning, including exemplary publications.

Empirical

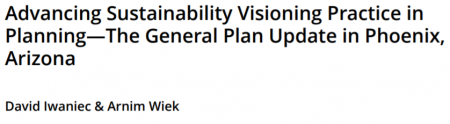

- Iwaniec, D.M. Wiek, A. 2014. Advancing Sustainability Visioning Practice in planning - The General Plan Update in Phoenix, Arizona. Planning Practice and Research.

Describes the Visioning process step by step in an exemplary project and draws conclusions on how the method may better be implemented in planning practice.

- Gaziulusoy, a.I. Ryan, C. 2017. Shifting Conversations for Sustainability Transitions Using Participatory Design Visioning. The Design Journal 20(1). 1916-1926.

Presents a project combining Visioning with Scenario Planning and other approaches in order to develop pathways for low-carbon cities in Australia.

- Elkins, L.A. Bivins, D. Holbrook, L. 2009. Community Visioning Process. A Tool for Successful Planning. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 13(4). 75-84.

Illustrates a project in a small US town where citizens were invited to develop visions and, subsequently, strategies for the future of their community.

References

(1) Wiek, A. Iwaniec, D.M. 2014. Quality criteria for visions and visioning in sustainability science. Sustainability Science 9. 497–512.

(2) Robinson, J.B. 1982. Energy backcasting: A proposed method of policy analysis. Energy Policy 10(4). 337-344.

(3) Davies, A.R. Doyle, R. Pape, J. 2012. Future visioning for sustainable household practices: spaces for sustainability learning? Area 44(1). 54-60.

(4) Constanza, R. 2000. Visions of alternative (unpredictable) futures and their use in policy analysis. Conservation Ecology 4(1).

(5) Gaziulusoy, a.I. Ryan, C. 2017. Shifting Conversations for Sustainability Transitions Using Participatory Design Visioning. The Design Journal 20(1). 1916-1926.

(6) Dreborg, K.H. 1996. Essence of backcasting. Futures 28(9). 813-828.

(7) Elkins, L.A. Bivins, D. Holbrook, L. 2009. Community Visioning Process. A Tool for Successful Planning. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 13(4). 75-84.

(8) Vergragt, P.J. Quist, J. 2011. Backcasting for sustainability: Introduction to the special issue. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 78. 747-755.

The author of this entry is Christopher Franz.