Ethics and Statistics

Following Sidgwicks "Methods of ethics", ethics can be defined as the world how it ought to be. Derek Parfit argued that if philosophy be a mountain, Western philosophy climbs it from three sides:

- The first side is Utilitarianism, which is widely preoccupied with the question how we can evaluate the outcome of an action. The most ethical choice would be the action that creates the most good for the largest amount of people.

- The second side is reason, which can be understood as the human capability to reflect what one is ought to do. Kant said much to this end, and Parfit associated it to the individual, or better, the reasonable individual.

- The third side of the mountain is the social contract, which states that a range of moral obligations are agreed upon in societies, a thought that was strongly developed by Locke. Parfit associated this even wider, referring to the whole society in his triple theory.

Contents

- 1 Do ethics matter for statistics?

- 2 Looking at ethics from statistics

- 3 Looking at statistics from philosophy of science

- 4 The imperfection of measurements

- 5 Of inabilities to compromise

- 6 Combining ethics and statistics

- 7 The Trolley problem

- 8 The way forward

- 9 One last thought: Statistics as a transformational experience towards ethics

- 10 Further Information

Do ethics matter for statistics?

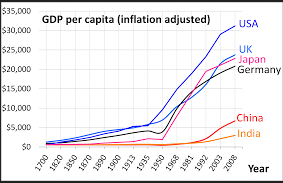

Personally, I think ethics matters deeply for statistics. Let me try to convince you. Looking at the epistemology of statistics, we learned that much of modern civilisation is built on statistical approaches, such as the design and analysis of Experiments or the correlation of two continuous variables. Statistics propelled much of the exponential growth in our society, and Statistics is responsible for many of the problems we currently face through our unsustainable behaviour. After all, Statistics was willing to utilize means and accomplish goals that led us more into the direction of a more unsustainable path. Many would argue now that if statistics were a weapon, itself would not kill. Instead, it would be the human hand that uses it. This is insofar true as statistics would not exist without us, just as weapons were forged by us. However, I would argue that statistics are still deeply normative, as they are associated with our culture, society, social strata, economies and so much more. This is why we should embrace a critical perspective on statistics. Much in our society depends on statistics, and many decisions are taken because of statistics. As we have learned, some of these statistics might be problematic or even wrong, and consequently, this can render the decisions wrong as well. More strangely, our statistics can be correct, but as we have learned, statistics can even then contribute to our downfall, for instance when they contribute to a process that leads to unsustainable production processes. We may calculate something correctly, but the result can be morally wrong. Ideally, our statistics would always be correct, and the moral implications that follow out of our actions that are informed by statistics are also right.

However, statistics is more often than not seen as something that is not normative, and some people consider statistics to create objective knowledge. This is rooted in the deep traditions and norms of the disciplines where statistics are an established methodological approach, and in the history and theory of science that governs our research. Many scientists are regrettably still positivists, and often consider the knowledge they create to be objective. More often than not, this is not a conscious choice, but the combination of unreflected teachers in some education system in general. Today, obvious moral dilemmas and ambiguities are generally part of complex ethical pre-checks in many study designs, for which medicine provides the gold standard. Here, preventing blunders was established early on, and is now part of the canon of many disciplines, with medicine leading the way. Such problems often deal with questions of sample size, randomisation and the question when a successful treatment should be given to all participants. These are indirect reflections on validity and plausibility within the study design, acknowledging that failures or flaws in these elements may lead to biased or even plain wrong results of the study.

What is however widely lacking within the broader debates in science is how the utilisation of statistics can have wider normative consequences, both during the application of statistics, but also due to the consequences that arise out of results that were propelled by statistics. In her book "Making comparisons count", Ruth Chang explores one example of such relations, but the gap between ethics and statistics is so large, we might define it altogether as widely undiscovered country. More will need to be done to overcome the gap between ethics and statistics, and a connection is hampered by the fact that both fields are widely unclear in terms of the overall accepted norms. While many statistical textbooks exist, these are more often than not disciplinary, and consolidating the field of ethics this diversity is certainly no small endeavour. Creating connections between statistics and ethics is a challenge, because there is a long history of flaws in this connection that triggered blurred, if not wrong decisions. We will therefore look at specific examples from both directions, starting with a view on ethics from the perspective of statistics.

Looking at ethics from statistics

When looking at the relation between ethics and statistics from the perspective of statistics, there are several items which can help us understand their interactions. First and foremost, the concept of validity can be considered to be highly normative. Two extreme lines of thinking come into mind: One technical, orientating on mathematical formulas; and the other line of thinking, being informed actually by the content. Both are normative, but of course there is a large difference between a model being correct in terms of a statistical validation, and a model approximating a reality that is valid. Empirical research makes compromises by looking at pieces of the puzzle of reality. Following critical realism, we may be able to unlock the strata of everything we can observe (the ‘empirical’, as compared to the ‘real’ and the ‘actual’), but ultimately this will always be a subjective perspective. Hence empirical research will always have to compromise as we choose versions of reality in our pursuit for knowledge.

If there is such a thing as general truth, you may find it in philosophy and probably thus also in ethics. Interestingly, philosophy originally served to generate criteria for validity in empirical research. However, knowledge in philosophy itself will never be empirical, at least not if it equally fulfils the criterion of being generally applicable. Through empirical research, we can observe and understand and thus generate knowledge, while philosophy is about the higher norms, principles and mechanism that transcend the empirical. Statistics is able to generate such empirical knowledge, and philosophy originally served to generate criteria for validity of this empirical process. Philosophy and empirical branches of science were vividly interacting in the Antique, they started to separate with the Enlightenment. The three concepts that (Western?) philosophy is preoccupied with - utilitarianism, reason and social contract - dissolved into scientific disciplines as economics, psychology, social science or political science. These disciplines subsequently tried to bridge the void between philosophy and empirical research, yet often had to settle for compromises when integrating the empirical versions of reality with higher theories from philosophy. An example would be the Friedman doctrine in economics, which was originally postulated with good intentions, but its empirical translation into policies wreaked havoc for whole nations.

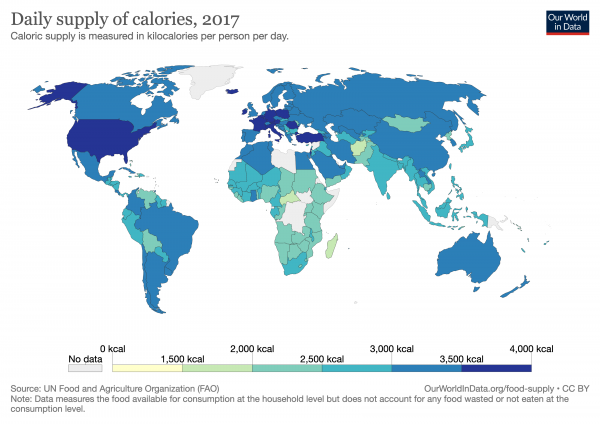

Statistics did however indirectly contribute to altering our moral values. Take utilitarianism. It depends deeply on our moral values how we calculate utility, and hence how we manage our systems through such calculations. Statistics in itself could be argued to be non-normative if it dealt with totally arbitrary data that has no connection to any reality. However, as soon as statistics deals with data of any version of reality, we make Statistics normative by looking at these versions of reality. It is our subjective views that make statistics no longer objective. One might argue that physics would be an exception, and it probably is. It is more than clear however that social sciences, economics, ecology and psychology offer subjective epistemological knowledge, at least from a viewpoint of critical realism. The numbers are clear, yet our view of them is not. Consider for instance that on the one hand, world hunger decreased over the last decades and more people get education or medical help than ever before. At the same time, other measures propose that inequality increases, for instance income inequality. While ethics can compare two statistical values in terms of their meaning for people, statistics can generate the baseline for this. Statistics provides the methodological design, mathematical calculations and experience in interpretation that we need to make ethical decisions. This brings us to plausibility.

Statistics builds on plausibility: a good model should be both probable and reasonable. While statistics focuses predominantly on probability, this is already a normative concept, as the significance level α is arbitrary (although the common level of .05 is more often than not relatively robust). However, p-values are partly prone to statistical fishing, which is why probability in statistics is widely established but still often prone to flaws and errors. For more on this, have a look at the entry on Bias in statistics.

Statistical calculations can also differ in terms of the model choice, which is deeply normative and a case of disciplinary schools of thinking. Many models build on the precondition of a normal distribution, which is however not always the case. This illustrates that assumed preconditions are often violated, and hence that statistical rigor can be subjective or normative. Different people have different experiences, and some parts of science are more rigorous than others. Non-normal distribution may matter deeply, for instance when it is about income inequalities and associated policies, and statistics shall not evade the responsibility that is implied in such an analysis.

Another example is the question of non-linearity. Preferring non-linear relationships to linear relationships is something that has become more important especially recently due to the wish to have a higher predictive power, to understand non-linear shifts, or for other reasons. Bending models - mechanically speaking - into a situation that allows to increase the model fit (that is, how much the model can predict) comes with the price that we sacrifice any possibility of causal understanding, since the zig-zag relations of non-linear models are often harder to match with our theories. While of course there are some examples of rapid shifts in systems, this has next to nothing to do with non-linearity that is assumed in many modern statistical analysis schemes and the predictive algorithms whose data power over us governs wide parts of our societies. Many disciplines gravitated towards non-linear statistics in the last decades, sacrificing explainable relationships for an ever increasing model fit. Hence the clear demarcation between deductive and inductive research became blurry, adding an epistemological/ontological burden on research. In many papers, the question of plausibility and validity has been deeply affected by this issue, and I would argue that this casts a shadow on the reputation of science. Philosophy alone cannot solve this problem, since it looks at the general side of reality. Only by teaming up with empirical research, we may arrive at measures of validity that are not on a high horse, but also can be connected to the real world. To this end, I would currently trust critical realism the most, yet time will tell where theory of science will lead us in the future.

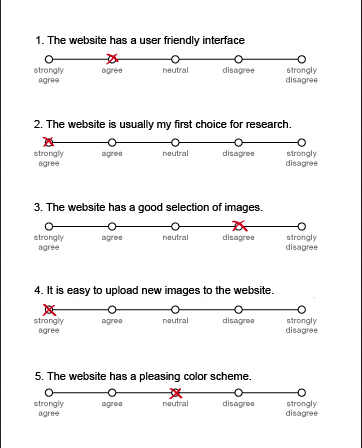

Another obvious example regarding the normativity of statistical analysis are constructs. Constructs are deeply normative, and often associated to existing norms within a discipline, and may even transcend whole world views. The Likert Scale in psychology is such an example. The obvious benefit of that scale is that it may unlock perceptions form a really diverse array of people, which is a positive aspect of such a scaling. Hence it became part of the established body of knowledge, and much experience is available on the benefits and drawbacks of this scaling, yet it is a normative choice whether we use it or not. Often, scales are even part of the tacit signature of cultural and social norms, and these indirectly influence the science that is conducted in this setting. An example would be the continuous Arabian numbering that dominates much of Western thinking, and that many of us grow into these days. Philosophy and especially cultural studies have engaged in such questions increasingly in the last decades, often focusing on isolated constructs or underlying fundamental aspects such as racism, colonialism and privilege. It will be challenging to link these important and timely concepts directly to the flaws of empirical research. These days, luckily, I recognize a greater awareness among empirical researchers to avoid errors implemented through such constructs. Much needs to be done, but I conceive reason for hope as well. Personally, I believe that constructs will always be associated to personal identity and thus pose a problem for a general acceptance. Time will tell if and how this gap can be bridged.

Looking at statistics from philosophy of science

Science often claims to create objective knowledge. Famously, Karl Popper and others stated that this claim is false - or should at least be questioned. Still, it is not only perceived by many people that science is de facto objective, but more importantly, many scientists often claim that the knowledge they produce is objective. Large parts of academia like to spread an air of superiority and arrogance, which is one of many explanations for the science-society-gap. When scientists should talk about potential facts, they often just talk about ‘facts’. When they could highlight our inability as scientists to grasp the true nature of reality, they instead present their version of reality to be the best or maybe even the only version of reality. Of course, this is not only their fault, since society increasingly demands easy explanations. A philosopher would be probably deeply disturbed if they understood how statistics are applied today, but even more disturbed if this philosopher saw how statistics are being interpreted and marketed. Precision and clarity in communicating results, as well as information on bias and caveats, are missing more often that we should hope for.

There are many facets that could be highlighted under such a provocative heading. Since Larry Laudan, it has become clear that the assumption that developments of science which are initiated by scientists are reasonable, is a myth at best. Take the example of one dominating paradigm in science right now: Publish or perish. This paradigm highlights the current culture dominating most parts of science. If you do not produce a large amount of peer-reviewed publications, your career will not continue. This created quite a demand on statistics as well, and the urge to arrive at significant results that probably created frequent violations of Occam's razor (that is, things should be as complex as necessary, but as simple as possible). The reproducibility crisis in psychology is one example of these developments, yet all other disciplines building on statistics struggle to this end, too. Another problem is the fact that with this ever-increasing demand for "scientific innovation", models evolve, and it is hard to catch up. Thus, instead of having robust and parsimonious models, there are more and more unsuitable and overcomplicated models. The level of statistics at an average certainly increased. There are counter-examples where this is not necessarily the case, and rightly so. In medicine, for instance, the canon of statistics is fairly established and solidified for large parts of the research landscape. Thus, while many innovative publications are exploring new ways of statistics, and a highly innovative to this end, there is always a well-defined set of statistical methods that research can default on. Within many other branches of science, however, there is a certain increase in errors or at least slippery slopes. Statistics are part of the publish or perish, and with this pressure still rising, unreasonable actions in the application of statistics may still increase. Many other examples exist to this end, but this should highlight that statistics is not only still developing further, but statistics should also keep evolving, otherwise we may not be able the diversity of epistemological knowledge it can offer.

The imperfection of measurements

As a next step, let us look at the three pillars of Western ethics and how these are intertwined with statistics. We all discuss how we act reasonable, how we can maximize our happiness and how we live together as people. Hence reason, utilitarianism and the social contract are all connected to statistics in one way or the other. While this complicated relation may in the future be explored in more than a short wiki entry, lets focus on some examples here.

One could say that utilitarianism created the single largest job boost for the profession of statisticians. From predicting economic development, to calculating engineering problems, to finding the right lever to tilt elections, statistics are dominating in almost all aspects of modern society. Calculating the maximisation of utility is one of the large drivers of change in our globalised economy. But it does not stop there. Followers on social media and reply time to messages are two of many factors how to measure success in life these day, often draining their direct human interactions in the process, and leading to distraction or even torment. Philosophy is deeply engaged in discussing these conditions and dynamics, yet statistics needs to embed these topics, which are strongly related to ethics, more into their curriculum. If we become mercenaries for people with questionable goals, then we follow a long string of people that maximised utility for better or worse. History teaches us of the horrors that were conducted in the process of utility maximisation, and we need to end this string of willing aids to illegitimate goals. Instead, statistics should not only be about numbers, but also about the fact that these numbers have meaning. Numbers are not abstract representations of the world, but can have different meanings for different people. Hence numbers can add information that is missing, and can serve as a starting point for an often necessary deeper reflection.

Of inabilities to compromise

Another problem that emerges out of statistics as seen from a perspective of ethics is the inability to accept different versions of reality. Statistics often arrives at a specific construction of reality, which is the confirmed or rejected. After all, most applications and interpretations in statistics are still from a standpoint of positivism. At best, such a version of reality becomes then more and more refined, until it becomes ultimately the accepted reality. Today, more people would agree that versions of reality are mere snapshots and are probable to change in the future. Linking our empirical snapshots or reality with ethical concepts I possible but challenging. Hedonism would be one example where statistics can serve as a blunt and unreflected tool, with the hedonist being the center of the universe. However, personal identity is increasingly questioned, and may play a different role in the future than it does today. We have to acknowledge that statistics is about epistemological knowledge, while ethics can be about ontological truths. Statistics may thus build a refined version of reality, while ethics can claim and alter between different realities that allow for the reflection of higher concepts or principles that transcend subjective realities and are thus non-empirical in a sense that these principles may be able to integrate all empirical realities. While this is one of the most daring endeavors in philosophy that emerged over the last decades, it builds on the premise that ethics can start lines of thinking outside of empirical realities. This freedom in ethics i.e., through Thought Experiments, is not possible in statistics. In Statistics, the empirical nature requires a high workload and time effort, which creates a penalty that ultimately makes statistics less able to compromise or integrate different versions of ethics. Future considerations need to clearly indicate what the limitations of statistics are, and how this problem of linking to other lines of thinking i.e. ethicscan be solved, even if such other worldviews violate statistical results or assumptions that characterize empirical realities. In other words, you can consider your subjective perspective as your epistemological reality, and I would argue that experience in statistics can enable you to develop a potentially better version of your epistemological reality. This may even change your ontological reality, as it can interact with your ontological principles, i.e. your moral views and ethical standpoints.

Combining ethics and statistics

A famous thought experiment from Derek Parfit is about 50 people dying of thirst in the desert. Imagine you could give them one glass of water, leaving a few drops for each person. This would not prevent them from dying, but it would still make a difference. You tried to help, and some would even argue, that if these people die, they still die with the knowledge that somebody tried to help them. Hence your actions may matter even if they are ultimately futile, yet classical ethics do not manage to account for such imperceptible consequences of our actions. Equally would a utilitarian statistician tell you that calculating the number of drops for each person is not only hard to measure, but would probably anyway evaporate before the people could sip it.

Another example is the tragic question of triage. Based on previous data and experience, it is sometimes necessary to prioritize patients with the highest chance of survival, for instance in the aftermath of a catastrophe. This has severe ethical ramifications and is known to put a severe emotional burden on medical personnel. While this follows a utilitarian approach, there are wider consequences that fall within the realms of medical ethics.

A third example is the repugnant conclusion. Are many quite happy people comparable to few very happy people? This question is widely considered to be a paradox, which is also known as the mere addition problem. We cannot ‘objectively’ measure happiness, and much less calculate it. What this teaches us is that it is difficult for us to judge whether a life is happy and worth living, even if we personally do not consider it to be this way. People can have fulfilled lives without us understanding this. Here, statistics fail once more, partly because of our normative perspective to interpret the different scenarios.

Another example, kindly borrowed from Daniel Dennet, are nuclear disasters. In Chernobyl many workers had to work under conditions that were creating a large harm to them, and a great emotional and medical burden. To this date, assumptions about the death toll vary widely. However, without their efforts it would be unclear what would have happened otherwise, as the molten nuclear lava would probably have reached the drainage water, leading to an explosion that might have rendered many parts of Eastern Europe uninhabitable. All these dynamics were hard to anticipate, and even more difficult to balance against the efforts of the workers. Basically, this disaster posed a wicked problem. One must state that these limitations of calculations and the evaluations of outcomes were already stated in Utilitarianism in Moore's Principia Ethics, but this has been widely overseen by many, who still guide their actions through imperfect predictions.

The Trolley problem

One last example of the relation between ethics and statistics is the problem of inaction. What if you could save 5 people, but you would know that somebody else then dies through the action that saves the other five. Many people prefer not to act. To them, an inaction is ethically more ok than the actual act, which would make them responsible for the death of one person, even if they saved five times as many people. This is also related to knowledge and certainty. Much knowledge exists that should lead people to act, but they prefer to not act at all. Obviously, this is a great challenge, and while psychology investigates this knowledge-action gap, I propose that it will still be here to stay for an unfortunately long time. If people were able to emotionally connect to information derived from numbers, just as the example above, and would be able to act reasonable, much harm could be avoided or at least minimised. This consequentialism is widely missing to date, albeit much of our constructed systems are based on quite similar rules. For instance, many people today do in fact understand that their actions have a negative impact on the climate, but nevertheless continue with these actions. Hence it is not only an inaction between knowledge and action, but also a gap between constructed systems and individuals. There is much to explore here, and as Martha Nussbaum rightly concluded in the Monarchy of Fear, even under dire political circumstances, "hope really is both a choice and a practical habit." Hence it is not only utilitarianism that links statistics to ethics, but these questions also links to the social contract, and how we act reasonably or unreasonably. Many experimental modifications of the Trolley experiment were investigated by Psychology, and these led to many interpretations on why people act unreasonably. One main result is that humans may tend to minimize the harm they do to others, even if this may create more harm to people on an indirect level. Pushing a lever is a different thing from pushing a person.

The way forward

The Feynman lectures provide the most famous textbook volumes on physics. Richard Feynman and his coauthors compiled these books in the 1960, yet to this day, many consider these volumes to be the most concise and understandable introduction to physics. Granted, Feynman's work is brilliant. At the same time, however, this fact also means that in the 1960s the majority of the knowledge necessary for an introduction in physics was already available. While we may consider that much happened ever since, students can still use these textbooks today. Something similar can be claimed for basic statistics, although it should be noted that physics is a scientific discipline, while statistics is a scientific method. Some disciplines use different methods, and many disciplines use statistics as a method. However, the final word on statistics has not been said, as the differences between probability statistics and Bayesian statistics are not yet deeply explored. Especially Bayesian statistics may provide a vital link to experiments, yet this has been hardly explored to date. Critical spirits may say that the teaching of statistics is often the most normal part of any sort of normal science study program, and this reputation led to statistics more often than not being characterized by a lack of excitement for students. We should not only know and teach the basics, but also engage in the discussion what these all may mean.

Philosophy can be thought together well with statistics. Unfortunately until today they are not very much associated with each other. Something surprisingly similar can be said about philosophy. While much of the basic principles are known, these are hardly connected. Philosophy hence works ever deeper on specifics, but most of its contributors move away from a unified line of thinking. This is what makes Derek Parfits work stand out, since he tried to connect the different dots, and it will be the work of the next decades to come to build on his work, and improve it if necessary.

While philosophy and statistics both face a struggle to align different lines of thinking, it is even more concerning how little these two are aligned with each other. Statistics make use of philosophy at some rare occasions, for instance when it comes to the ethical dilemmas of negatively affecting people that are part of a study. While these links are vital for the development of specific aspects of statistics, the link between moral philosophy and statistics has hardly been explored so far. In order to enable statistics to contribute to the question how we ought to act, a systematic interaction is needed. I propose that exploring possible links is a first step, and we start to investigate how such connections work. The next step would be the proposal of a systematic conceptualisation of these different connections. This conceptualisation would then need to be explored and amended, and this will be very hard work, since both statistics and moral philosophy are scattered due to a lack of a unified theory, and hardly anyone is versatile in both fields.. This makes a systematic exploration of such a unifying link even more difficult to explore is the question who would actually do that. Within most parts of the current educational system, students learn either empirical research and statistics, or the deep conceptual understanding of philosophy. Only when we enable more researcher to approach from both sides - empirical and conceptual - will we become increasingly able to bridge the gap between these two worlds.

One last thought: Statistics as a transformational experience towards ethics

Most links between statistics and ethics are tacit, sparse and more often than not singular. Overall, the link is difficult to establish because much of ethics are about concepts and thus holistic ways of thinking, while statistics engages in the empirical, which is after all subjective. I would however argue that it is still possible to link these two, and to illustrate this I use the example of Occam’s razor. Remember: “Everything needs to be as simple as possible, and as complex as necessary”. I would propose now that Occam’s razor is not really a principle - like justice or altruism - but a heuristic. Heuristics can help us guide our actions, or better, the way we act. To this end, we must consider that Occam’s razor is different to different people, since 'simple' or 'complex' may mean different things to them. Take an advanced statistical dataset. To me, this is probably a quite straightforward endeavour to analysis this, while for some of you, an analysis and hence the dataset and your view of it are rather complex. Another important point is that different branches of science have different approaches to defining complexity, posing another reason why this is a subjective or normative perspective on the simple and the complex. The process of balancing simplicity and complexity is however a process that would argue to be objective, in a sense that we all struggle to balance the simple and the complex. This process of reflection can be a quite catalytic experience, and this learning - I would argue - unites us all. Hence Ocam’s razor is partly about epistemological knowledge, and partly about ontological truth. I believe this can make the case that Occam’s razor provides a link between statistics and ethics, since within ethics we can discuss how we negotiate, mitigate, and integrate in a reflexive way the balance between the simple and the complex.

Further Information

Articles

The Methods of Ethics: The whole book by the famous Henry Sidgwick

Derek Parfit: A short biography & a summary of his most important thoughts

and Food Provision: some data

dredging: An introduction into statistical fishing

Ethics & Statistics: A guideline

The Science-Society Gap: An interesting paper on the main issues between science and society

Utilitarianism & Economics: A few words from the economic point of view

Videos

Utilitarianism: An introduction with many examples

The Nature of Truth: some thoughts from philosophy

Model Fit: An explanation using many graphs and example calculations

The author of this entry is Henrik von Wehrden.