Social Network Analysis

| Method categorization | ||

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Qualitative | |

| Inductive | Deductive | |

| Individual | System | Global |

| Past | Present | Future |

In short: Social Network Analysis visualises social interactions as a network and analyzes the quality and quantity of connections and structures within this network.

Background

One of the originators of Network Analysis was German philosopher and sociologist Georg Simmel. His work around the year 1900 highlighted the importance of social relations when understanding social systems, rather than focusing on individual units. He argued "against understanding society as a mass of individuals who each react independently to circumstances based on their individual tastes, proclivities, and beliefs and who create new circumstances only by the simple aggregation of their actions. (...) [W]e should focus instead on the emergent consequences of the interaction of individual actions." (Marin & Wellman 2010, p.6)

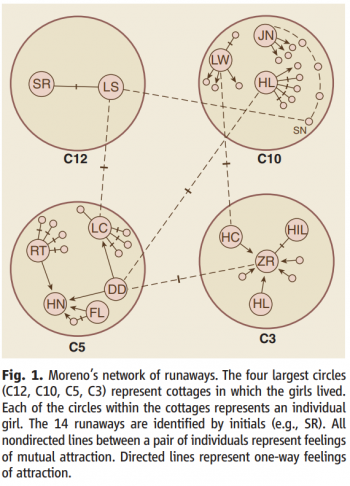

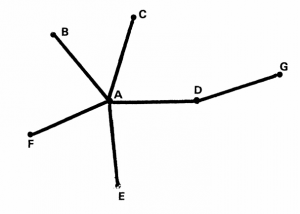

Romanian-American psychosociologist Jacob Moreno heavily influenced the field of Social Network Analysis in the 1930s with his - and his collaborator Helen Jennings' - 'sociometry', which served "(...) as a way of conceptualizing the structures of small groups produced through friendship patterns and informal interaction." (Scott 1988, p.110). Their work was sparked by a case of runaways in the Hudson School for Girls in New York. Their assumption was that the girls ran away because of the position they occupated in their social networks (see Diagram).

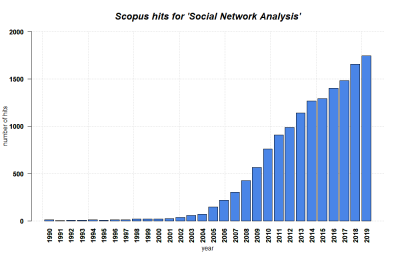

Moreno's and Jennings' work was subsequently taken up and furthered as the field of 'group dynamics', which was highly relevant in the US in the 1950s and 1960s. Simultaneously, sociologists and anthropologists further developed the approach in Britain. "The key element in both the American and the British research was a concern for the structural properties of networks of social relations, and the introduction of concepts to describe these properties." (Scott 1988, p.111). In the 1970s, Social Network Analysis gained even more traction through the increasing application in fields such as geography, economics and linguistics. Sociologists engaging with Social Network Analysis remained to come from different fields and topical backgrounds after that. Two major research areas today are community studies and interorganisational relations (Scott 1988; Borgatti et al. 2009). However, since Social Network Analysis allows to assess many kinds of complex interaction between entities, it has also come to use in fields such as ecology to identify and analyze trophic networks, in computer science, as well as in epidemiology (Stattner & Vidot 2011, p.8).

What the method does

"Social network analysis is neither a theory nor a methodology. Rather, it is a perspective or a paradigm." (Marin & Wellman 2010, p.17) It subsumes a broad variety of methodological approaches; the fundamental ideas will be presented hereinafter.

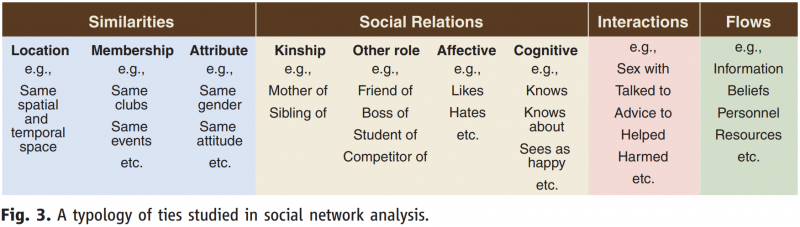

Social Network Analysis is based on the idea that "(...) social life is created primarily and most importantly by relations and the patterns formed by these relations. Social networks are formally defined as a set of nodes (or network members) that are tied by one or more types of relations." (Marin & Wellman 2010, p.1; Scott 1988). These network members are also commonly referred to as "entitites", "actors", "vertices" or "agents" and are most commonly persons or organizations, but can in theory be anything (Marin & Wellman 2010). The nodes are "(...) tied to one another through socially meaningful relations" (Prell et al. 2009, p.503), which can be "(...) collaborations, friendships, trade ties, web links, citations, resource flows, information flows (...) or any other possible connection" (Marin & Wellman 2010, p.2). It is important to acknowledge that each node can have has different relations to all other nodes, spheres and levels of the network. Borgatti et al. (2009) refer to four types of relations in general: similarities, social relations, interactions, and flows.

The Social Network Analyst then analyzes these relations "(...) for structural patterns that emerge among these actors. Thus, an analyst of social networks looks beyond attributes of individuals to also examine the relations among actors, how actors are positioned within a network, and how relations are structured into overall network patterns." (Prell et al. 2009, p.503). Social Network Analysis is thus not the study of relations between individual pairs of nodes, which are referred to as "dyads", but rather the study of patterns within a network. The broader context of each connection is of relevance, and interactions are not seen independently but as influenced by the adjacent network surrounding the interaction. This is an important underlying assumption of Social Network Theory: the behavior of similar actors is based not primarily on independently shared characteristics between different actors within a network, but rather merely correlates with these attributes. Instead, it is assumed that the actors' behavior emerges from the interaction between them: "Their similar outcomes are caused by the constraints, opportunities, and perceptions created by these similar network positions." (Marin & Wellman 2010, p.3). Surrounding actors may provide leverage or influence that affect the agent's actions (Borgatti et al. 2009)

Step by Step

- Type of Network: First, Social Network Analysts decide whether they intend to focus on a holistic view on the network (whole networks), or focus on the network surrounding a specific node of interest (ego networks). They also decide for either one-mode networks, focusing on one type of node that could be connected with any other; or two-mode networks where there are two types of nodes, with each node unable to be connected with another node of the same type (Marin & Wellman 2010, 13). For a two-mode network, you could imagine an analysis of social events and the individuals that visit these, where each event is not connected to another event, but only to other individuals; and vice-versa.

-

Network boundaries: In a next step, the approach to defining nodes needs to be chosen. Three ways of defining networks can be named according to Marin & Wellman (2010, p.2, referring to Laumann et al. (1983)). These three are approaches not mutually exclusive and may be combined:

- position-based approach: considers those actors who are members of an organization or hold particular formally-defined positions to be network members, and all others would be excluded

- event-based approach: those who had participated in key events are believed to define the population

- relation-based approach: begins with a small set of nodes deemed to be within the population of interest and then expands to include others sharing particular types of relations with those seed nodes as well as with any nodes previously added.

- Butts (2008) adds the exogenously defined boundaries, which are pre-determined based on the research intent or theory which provide clearly specified entities of interest.

- Type of ties: Then, the researcher needs to decide on which kinds of ties to focus. There can be two forms of ties between network nodes: directed ties, which go from one node to another, and undirected ties, that connect two nodes without any distinct direction. Both types can either be binary (they exist, or do not exist), or valued (they can be stronger or weaker than other ties): As an example, "(..) a friendship network can be represented using binary ties that indicate if two people are friends, or using valued ties that assign higher or lower scores based on how close people feel to one another, or how often they interact." (Marin & Wellman 2010, p.14; Borgatti et al. 2009)

- Data Collection: When the research focus is chosen, the data necessary for Social Network Analysis can be gathered in Surveys or Interviews, through Observation, Content Analysis (typically literature-based) or similar forms of data gathering. Surveys and Interviews are most common, with the researchers asking individuals about the existence and strength of connections between themselves and others actors, or within other actors excluding themselves (Marin & Wellman 2010, p.14). There are two common approaches when surveying individuals about their own connections to others: In a prompted recall approach, they are asked which people they would think of with regards to a specific topic (e.g. "To whom would you go for advice at work?") while they are shown a pre-determined list of potentially relevant individuals. In the free list approach, they are asked to recall individuals without seeing a list (Butts 2008, p.20f).

-

Data Analysis: When it comes to analyzing the gathered data, there are different network properties that researchers are interested in in accordance with their research questions. The analysis may be qualitative as well as quantitative, focusing either on the structure and quality of connections or on their quantity and values. (Marin & Wellman 2010, p.16; Butts 2008, p.21f). The analysis can focus on

- the quantity and quality of ties that connect to individual nodes

- the similarity between different nodes, or

- the structure of the network as a whole in terms of density, average connection length and strength or network composition.

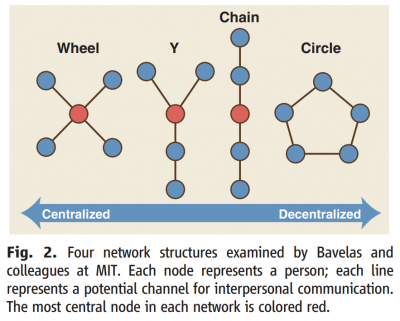

- An important element of the analysis is not just the creation of quantitative or qualitative insights, but also the visual representation of the network. For this, the researcher "(...) will naturally seek the clearest visual arrangement, and all that matters is the pattern of connections." (Scott 1988, p.113) Based on the structure of the ties, the network can take different forms, such as the Wheel, Y, Chain or Circle shape.

Importantly, the actual distance between nodes is thus not equatable with the physical distance in a visualisation. Instead, the actual distance between elements of the network should be measured based on the "number of lines which it is necessary to traverse in order to get from one point to another." (Scott 1988, p.114)

Strengths & Challenges

- There is a range of challenges in the gathering of network data through Interviews and Surveys, which can become long and cumbersome, and in which the interviewees may differently understand and recall their relations with other actors, or misinterpret the connections between other actors. (Marin & Wellman 2010, p.15)

- The definition of network boundaries is crucial, since "(...) the inappropriate inclusion or exclusion of a small number of entities can have ramifications which extend well beyond those entities themselves". Apart from the excluded entities and their relations, all relations between these entities and the rest of the network, and thus the network's structural properties, are affected. (Butts 2008). For more insights on the topic of System Boundaries, please refer to the respective article.

Normativity

- The structure of any network and thus the conclusions that can be drawn in the analysis very much depend on the relation that is observed. A corporation may be differently structured in terms of their informal compared to their official communication structures, and an individual may not be part of one network but central in another one that focuses on a different relational quality (Butts 2008)

- Further, the choice of network boundaries as well as the underlying research intent can have normative implications. Also, actors within the network may be characterized using specific attributes, which may be a normative decision (such as for attributes of ethnicity, violence, or others).

- The method of social network analysis is connected to the methods Stakeholder Analysis as well as Clustering. Further, as mentioned above, the data necessary for Social Network Analysis can be gathered in Surveys or Interviews, through Observation, Content Analysis or similar methods of data gathering. Last, the whole idea of analyzing systemic interactions between actors is the foundational idea of Systems Thinking.

An exemplary study

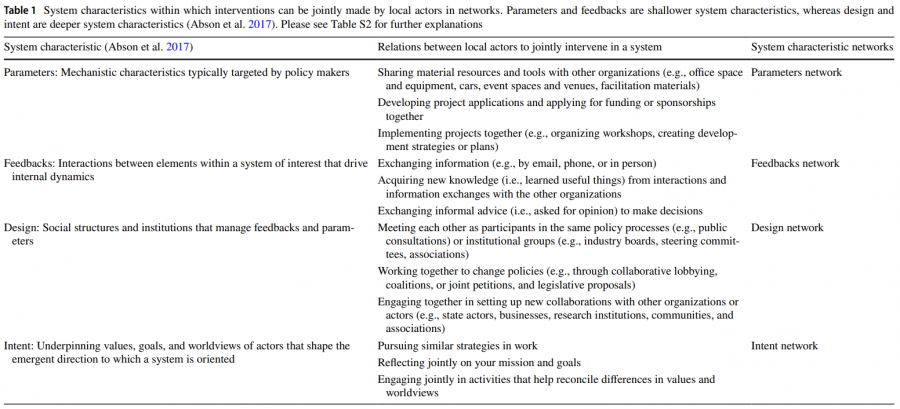

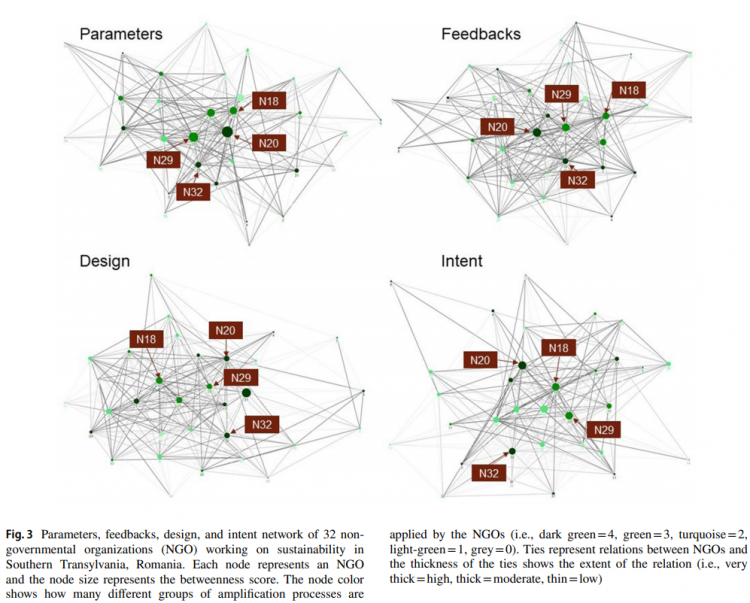

In their 2021 publication, researchers from Leuphana (Lam et al., see References) investigated the network ties between 32 NGOs driving sustainability initiatives in Southern Transylvania. Based on the leverage points concept, they attempted to identify how these NGOs contribute to systemic change. For this, they focused on the positions of the NGOs in different networks, with each network representing relations that target different system characteristics (parameters, feedbacks, design, intent). As a basis for this, the authors identified types of ties between the NGOs that contribute to each of these four system characteristics.

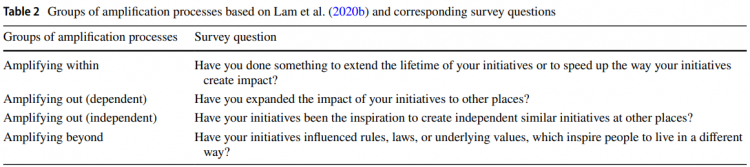

Further, they investigated the amplification processes the NGOs applied to their initiatives to foster transformative change, grouped into four kinds of amplification processes: within, out (dependent), out (independent) and beyond.

Based on these conceptual structures, the authors conducted an online survey in which 30 NGOs participated. In this survey, the NGOs were asked about their relations to other NGOs in terms of the kinds of questions shown above relating to the four leverage points. The NGOs were asked to rate the strength of the respective relations to another NGOs over the past five years with either "not at all" (0), low extent (1), moderate extent (2), high extent (3), and "I don't know". Further, the survey asked the NGOs four questions about the four kinds of amplification as shown above.

With the survey data, the authors created four networks using Gephi and NodeXL software, one for each system characteristic. For each NGO (= node), they calculated three measures (Lam et al. 2021, p.816):

- the weighted degree, which measures the relations of the node to other nodes in the network, taking into consideration the weight of the relations. This measure provides insights on each node's individual interconnectedness.

- the betweenness, which highlights how often a node links other nodes that would otherwise be unconnected. The higher the betweenness of a node is, the more power it exerts on the network.

- the eigenvector centrality, which measures the influence of a node in the network, weighted by the influence of its neighboring nodes. This highlights the future influence of a node.

They additionally tested for the influence of each NGO's amplification actions on these network measures by comparing those NGOs that applied a specific amplification action to those that did not, using a Mann-Whitney U test (also known as Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

In their results, they "(...) found that while some NGOs had high centrality metrics across all four networks (...), other NGOs had high weighted degree, betweenness, or eigenvector in one particular network." (p.817)

Without going into too many details at this point, we can see that the created networks tell us a lot about different aspects of the relation between actors. Based on the shown and further results, the authors concluded that

- actors (NGOs) may have central roles either concerning all kinds of networks, or just in specific networks,

- actors that amplify their own impact actively are potentially more central in networks, and

- that Social Network Analysis with a leverage points perspective can help identify how and which actors play an important role for different kinds of sustainability transformations.

For more on this study, please refer to the References.

Key publications

- Scott, J. 1988. Trend Report Social Network Analysis. Sociology 22(1). 109-127.

- Borgatti, S.P. et al. 2009. Network Analysis in the Social Sciences. Science 323. 892-895.

- Rowley, TJ. 1997. Moving beyond dyadic ties: A network theory of stakeholder influences. Academy of Management Review 2284). 887-910.

- Bodin, Ö., Crona, B., Ernstson, H. 2006. Social networks in natural resource management: What is there to learn from a structural perspective? Ecology and Society 11(2).

- Wasserman, S., Faust, K. 1994. Social network analysis: Methods and applications (Vol. 8). Cambridge university press.

- Prell, C. (2012): Social network analysis: History, theory and methodology, London.

- Reed, M.S., Graves, A., Dandy, N., Posthumus, H., Hubacek, K., Morris, J., Prell, C., Quinn, C.H., Stringer, L.C. 2009. Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. Journal of Environmental Management 90, 1933-1949.

References

(1) Marin, A. Wellman, B. 2009. Social Network Analysis: An Introduction. In: SAGE Handbook of Social Network Analysis. 2010.

(2) Scott, J. 1988. Trend Report Social Network Analysis. Sociology 22(1). 109-127.

(3) Butts, C.T. 2008. Social network analysis: A methodological introduction. Asian Journal of Social Psychology 11. 13-41.

(4) Borgatti, S.P. et al. 2009. Network Analysis in the Social Sciences. Science 323. 892-895.

(5) Prell, C. Hubacek, K. Reed, M. 2009. Stakeholder Analysis and Social Network Analysis in Natural Resource Management. Society and Natural Resources 22. 501-518.

(6) Stattner, E. Vidot, N. 2011. Social network analysis in epidemiology Current trends and perspectives. Research Challenges in Information Science

(7) Lam, D.P.M. Martín-López, B. Horcea-Milcu, A.I. Lang, D.J. 2021. A leverage points perspective on social networks to understand sustainability transformations: evidence from Southern Transylvania. Sustainability Science 16. 809-826.

Further Information

- An introduction to Social Network Analysis incl. R coding guidance by Mod-U: Powerful Concepts in Social Science on YouTube.

The author of this entry is Christopher Franz.