Difference between revisions of "Delphi"

| (56 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

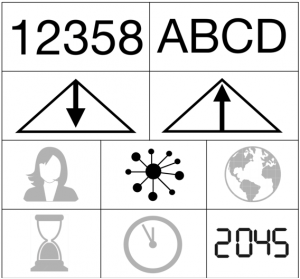

| − | [[ | + | [[File:Quan qual dedu indu syst futu.png|thumb|right|[[Design Criteria of Methods|Method Categorisation:]]<br> |

| + | '''Quantitative''' - '''Qualitative'''<br> | ||

| + | '''Deductive''' - '''Inductive'''<br> | ||

| + | Individual - '''System''' - Global<br> | ||

| + | Past - Present - '''Future''']] | ||

| + | '''In short:''' The Delphi Method is an interactive form of data gathering in which expert opinions are summarized and consensus is facilitated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Background == | ||

| + | The Delphi method originates from work at RAND Corporation, a US think-tank that advises the US military, in the late 1940s and 1950s (2, 3, 5). RAND developed "Project Delphi" as a mean of obtaining "(...) the most reliable consensus of opinion of a group of experts." (Dalkey & Helmer 1963, p.1). At the time, the alternative - extensive gathering and analysis of quantitative data as a basis for forecasting and deliberating on future issues - was not technologically feasible (4, 5). Instead, experts were invited and asked for their opinions - and Delphi was born (see (1)). | ||

| + | |||

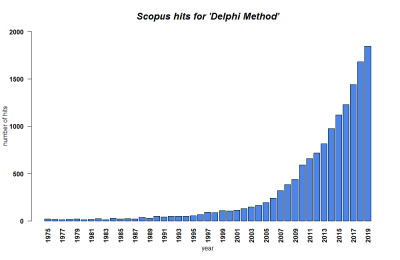

| + | [[File:Delphi Method SCOPUS.png|400px|thumb|right|'''SCOPUS hits for the Delphi method until 2019.''' Search terms: 'Delphi Panel', 'Delphi Method', 'Delphi Methodology', 'Delphi Study', 'Delphi Survey' in Title, Abstract, Keywords. Source: own.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1964, a RAND report from Gordon & Helmer brought the method to attention for a wider audience outside the military defense field (4, 5). Subsequently, Delphi became a prominent method in technological forecasting; it was also adapted in management; in fields such as drug policy, education, urban planning; and applied in order to understand economic and social phenomena (2, 4, 5). An important field today is the healthcare sector (7). While during the first decade of its use the Delphi method was mostly about forecasting future scenarios, a second form was developed later that focused on concept & [[Glossary|framework]] development (3). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Delphi was first applied in these non-scientific fields before it reached academia (4). Here, it can be a beneficial method to identify topics, questions, terminologies, constructs or theoretical perspectives for research endeavours (3). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == What the method does == | ||

| + | The Delphi method is "(...) a systematic and interactive research technique for obtaining the judgment of a panel of independent experts on a specific topics" (Hallowell & Gambatese 2010, p.99). It is used "(...) to obtain, exchange, and develop informed opinion on a particular topic" and shall provide "(...) a constructive forum in which consensus may occur" (Rayens & Hahn 2000, p.309). Put simply, experts on a topic are gathered and asked in a systematic process what they think about the future, until consensus is found. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== The Delphi procedure ==== | ||

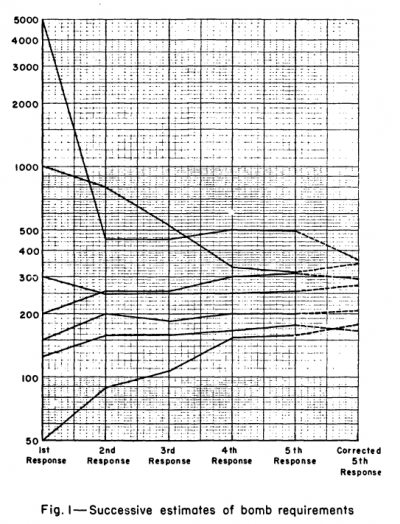

| + | [[File:ResultVisualisationDelphi.png|400px|thumb|right|Questionnaire results for the original RAND study, asking for an estimate of bomb requirements. The estimated numbers per participant converge over the course of the Delphi procedure. Source: Dalkey & Helmer 1963, p.15]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''A Delphi process typically undergoes four phases''' (see (4), (6)): | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1. A group of experts / stakeholders on a specific issue is identified and invited as participants for the Delphi. These participants represent different backgrounds: academics, government and non-government officials as wel, as practitioners. They should have a diverse set of perspectives and profound knowledge on the discussed issues. They may be grouped based on their organizations, skills, disciplines or qualifications (3). Their number typically ranges from 10 up to 30, depending on the complexity of the issue (2, 3, 5, 6). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The researchers then develop a questionnaire. It is informed by previous research as well as input from external experts (not the participants) who are asked to contribute knowledge and potential questions on the pertinent issue (2, 5). The amount of [[Glossary|consultation]] depends on the expertise of the researchers on the respective issue (2). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2. The questionnaire is used to ask for the participants' opinions and positions related to the underlying issue. The questions often take a 'ranking-type' (3): they ask about the likelihood of potential future situations, the desirability of certain goals, the importance of specific issues and the feasibility of potential policy options. Participants may be asked to rank the answer options, e.g. from least to most desirable, least to most feasible etc. (2). Participants may also be asked yes/no questions, or to provide an estimate as a number. They can provide further information on their answers in written form. (8) | ||

| + | |||

| + | The questioning is most commonly conducted in form of a questionnaire but has more recently also been realized as individual, group, phone or digital interview sessions (2, 5). Digital questioning allows for real-time assessments of the answers and thus a quicker process. However, a step-by-step procedure provides more time for the researchers to analyze the responses (4). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3. After the first round, the participants' answers are analyzed both in terms of tendency and variability. The questionnaire is adapted to the new insights: questions that already indicated consensus on a specific aspect of the issue are abandoned while disagreements are further included. 'Consensus' may be defined based on a certain percentage of participants agreeing to one option, the median of the responses or a degree of standard deviation, among other definitions (2, 5, 6, 7). New questions may be added to the questionnaire and existing questions may be rephrased based on the first set of answers (4). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Next, the experts are again asked for their opinions on the newly adapted set of questions. This time, the summarized but - this is important - anonymous group results from the first round are communicated to them. This feedback is crucial in the Delphi method. It incentivizes the participants to revise their previous responses based on their new knowledge on the group's positions and thus facilitates consensus. The participants may also provide reasons for their positions (5, 6). Again, the results are analyzed. The process continues in several rounds (typically 2-5) until a satisfactory degree of consensus among all participants is reached (2-6). | ||

| + | |||

| + | 4. Finally, the results of the process are summarized and evaluated for all participants (4). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == Strengths & Challenges == | ||

| + | The literature indicates a variety of benefits that the Delphi method offers. | ||

| + | * Delphi originally emerged due to a lack of data that would have been necessary for traditional forecasting methods. To this day, such a lack of empirical data or theoretical foundations to approach a problem remains a reason to choose Delphi. Delphi may also be an appropriate choice if the collective subjective judgment by the experts is beneficial to the problem-solving process (2, 4, 5, 6). | ||

| + | * Delphi can be used as a form of group counseling when other forms, such as face-to-face interactions between multiple stakeholders, are not feasible or even detrimental to the process due to counterproductive group dynamics (4, 5). | ||

| + | * The value of the Delphi method is that it reveals clearly those ideas that are the reason for disagreements between stakeholders, and those that are consensual (5). | ||

| + | * Delphi can be "(...) a highly motivating experience for participants" (Rayens & Hahn 2000, p.309) due to the feedback on the group's opinions that is provided in subsequent questioning stages. | ||

| + | * The Delphi method with its feedback characteristic has advantages over direct confrontation of the experts, which "(...) all too often induces the hasty formulation of preconceived notions, an inclination to close one's mind to novel ideas, a tendency to defend a stand once taken, or, alternatively and sometimes alternately, a predisposition to be swayed by persuasively stated opinions of others." (Okoli & Pawlowski 2004, p.2, after Dalkey & Helmer) | ||

| + | * Additionally, Delphi provides several advantages over traditional surveys: | ||

| + | ** Studies have shown that averages of group responses are superior to averages of individual responses. (3) | ||

| + | ** Non-response and drop-out of participants is low in Delphi processes. (3) | ||

| + | ** The availability of the experts involved allows for the researchers to (a) get their precognitions on the issue verified by the participating experts and to (b) gain further qualitative data after the Delphi process. (3) | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, several potential pitfalls and challenges may arise during the Delphi process: | ||

| + | * Delphi should not be used as a surrogate for every other type of communication - it is not feasible for every issue (4, 5, 6). | ||

| + | * A specific Delphi format that was useful in one study must not work as well in another context. Instead, the process must be adapted to the research design and underlying problem (4). | ||

| + | * The proper selection of participating experts constitutes a major challenge for Delphi processes (3, 4, 5, 6). In addition, the researchers should be aware that any expert is likely to forecast based on their specific sub-system perspective and might neglect other factors (4). | ||

| + | * The monitor (= researcher) must not impose their own preconceptions upon the respondents when developing the questionnaire but be open for contributions from the participants. The questions should be concise and understandable and should not incentivise the participant to "get the job over with" (Linstone & Turoff 1975, p.568; 5). | ||

| + | * Diverse forms of [[Glossary|bias]] might occur on the part of the participants that need to be anticipated by the researcher. These include discount of the future, over-optimism / over-pessimism, misinterpretations with regard to the complexity and uncertainty involved in forecasting the future as well as other forms of bias that may be imposed through the feedback process (4, 6). | ||

| + | * The responses must be adequately summarized, analyzed and presented to the participants (see the variety of measures for 'consensus' in What the method does)). "Agreement about a recommendation, future event, or potential decision does not disclose whether the individuals agreeing did so for the same underlying reasons. Failure to pursue these reasons can lead to dangerously false results." (Linstone & Turoff 1975, p.568). | ||

| + | * Disagreements between participants should be explored instead of being ignored so that the final consensus is not artificial (4). | ||

| + | * The participants should be recompensated for their demanding task (4) | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == Normativity == | ||

| + | ==== Connectedness / nestedness ==== | ||

| + | * While Delphi is a common forecasting method, backcasting methods (such as [[Visioning & Backcasting|Visioning]]) or [[Scenario Planning]] may also be applied in order to evaluate potential future scenarios without tapping into some of the issues associated with forecasting (see more in the [[Visioning|Visioning]] entry) | ||

| + | * Delphi, and the conceptual insights gathered during the process, can be a starting point for subsequent research processes. | ||

| + | * Delphi can be combined with qualitative or quantitative methods beforehand (to gain deeper insights into the problem to be discussed) and afterwards (to gather further data). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Everything normative related to this method ==== | ||

| + | * The Delphi method is highly normative because it revolves around the subjective opinions of stakeholders. | ||

| + | * The selection of the participating experts is a normative endeavour and must be done carefully so as to ensure a variety of perspectives. | ||

| + | * Delphi is an instrument of [[Transdisciplinarity|transdisciplinary]] research that may be used both to find potential policy options as well as to further academic proceedings. Normativity is deeply rooted in this connection between academia and the 'real-world'. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == Outlook == | ||

| + | ==== Open questions ==== | ||

| + | * The diverse fields in which the Delphi method was applied has diversified and thus potentially confounded its methodological homogeneity, raising the need for a more comparable application and reporting of the method (6, 7) | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == An exemplary study == | ||

| + | [[File:Delphi - Exemplary study Kauko & Palmroos 2014 title.png|600px|frameless|center|The title of the exemplary study for Delphi method. Source: kauko & Palmroos 2014]] | ||

| + | In their 2014 publication, Kauko & Palmroos present their results from a Delphi process with financial experts in Finland. They held a Delphi session with five individuals from the Bank of Finland, and the Financial Supervisory Authority of Finland, each. Every individual was anonymized with a self-chosen pseudonym so that the researchers could track the development of their responses. '''The participants were asked questions in a questionnaire that revolved around the close future of domestic financial markets.''' Specifically, the participants were asked to numerically forecast 15 different variables (e.g. stock market turnover, interest in corporate loans, banks' foreign net assets etc.) with simple point estimates. These variables were chosen to "fall within the field of expertise of the respondents, and at the same time be as independent of each other as possible." (p.316). The participants were provided with information on the past developments of each of these variables. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The researchers decided to go with three rounds until consensus should be reached. For the first round, questionnaires were distributed by mail, and the participants had one week to answer them. The second and third round were held on the same day after this one-week period. '''The responses from the respective previous round were re-distributed to the participants''' (each individual answer including additional comments, as well as the group average and the median for each variable). The participants were asked to consider this information, and answer all 15 questions - i.e., forecast all 15 variables - again. | ||

| + | |||

| + | After the third round, the participants were additionally asked to fill out survey questions on a 1-5 [[Likert Scale]] about how reliable their considered their own forecasts, and how much attention they had paid to the others' forecasts and comments when these were re-distributed, both regarding each variable individually. This was done to better understand each individual's thought process. | ||

| + | <br> | ||

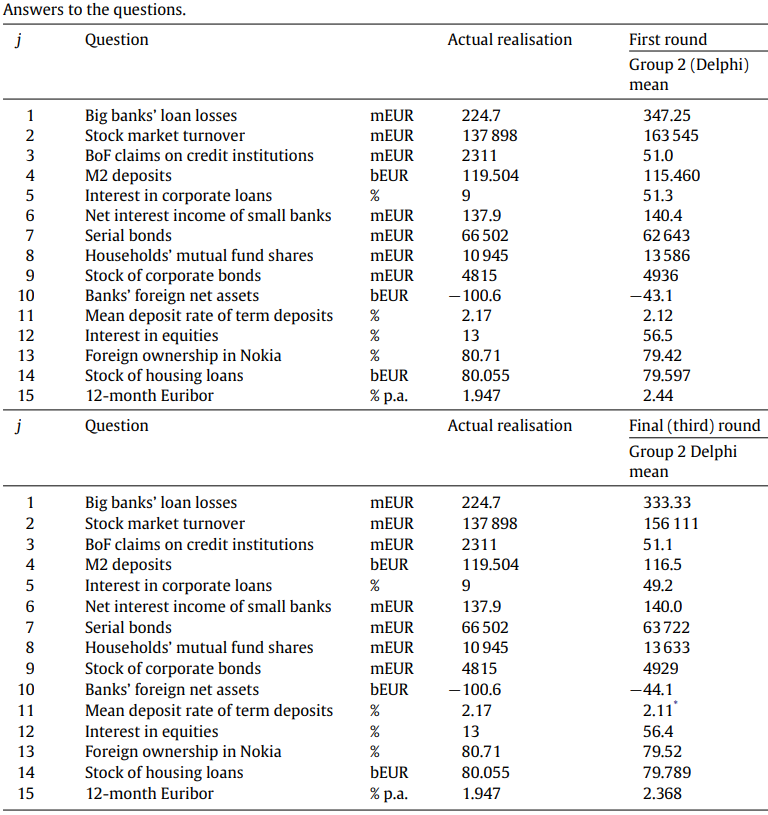

| + | [[File:Delphi - Exemplary study Kauko & Palmroos 2014 results.png|800px|thumb|center|'''The results for the Delphi process.''' It shows that the mean estimates of the group became better over time, and were most often quite close to the actual realisation. Source: Kauko & Palmroos 2014, p.326.]] | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | The forecasting results from the Delphi process could be verified or falsified with the real developments over the next months and years, so that the researchers were able to check whether the responses actually got better during the Delphi process. '''They found that the individual responses did indeed converge over the Delphi process, and that the "Delphi group improved between rounds 1 and 3 in 13 of the questions."''' (p.320). They also found that "[d]isagreeing with the rest of the group increased the probability of adopting a new opinion, which was usually an improvement" (p.322) and that the Delphi process "clearly outperformed simple trend extrapolations based on the assumption that the growth rates observed in the past will continue in the future", which they had calculated prior to the Delphi (p.324). Based on the post-Delphi survey answers, and the results for the 15 variables, the researchers further inferred that "paying attention to each others' answers made the forecasts more accurate" (p.320), and that the participants were well able to assess the accuracy of their own estimates. The researchers calculated many more measures and a comparison to a non-Delphi forecasting round, which you can read more about in the publication. Overall, this example shows that the Delphi method works in that it leads to more accurate results over time, and that the process itself helps individuals better forecast than traditional forecasts would. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | == Key Publications == | ||

| + | * Linstone, H. Turoff, M. 1975. ''The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications''. Addison-Wesley, Boston. | ||

| + | An extensive description of the characteristics, history, pitfalls and philosophy behind the Delphi method. | ||

| + | * Dalkey, N. Helmer, O. 1963. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management Science 9(3). 458-467. | ||

| + | The original document illustrating the first usage of the ''Delphi'' method at RAND. | ||

| + | * Gordon, T.J. Helmer, O. 1964. Report on a long-range forecasting study. RAND document P-2982. | ||

| + | The report that popularized ''Delphi'' outside of the military defense field. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == References == | ||

| + | * (1) Dalkey, N. Helmer, O. 1963. ''An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts.'' Management Science 9(3). 458-467. | ||

| + | * (2) Rayens, M.K. Hahn, E.J. 2000. ''Building Consensus Using the Policy Delphi Method''. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice 1(4). 308-315. | ||

| + | * (3) Okoli, C. Pawlowski, S.D. 2004. ''The Delphi Method as a Research Tool: An Example, Design Considerations and Applications.'' Information & Management 42(1). 15-29. | ||

| + | * (4) Linstone, H. Turoff, M. 1975. ''The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications''. Addison-Wesley, Boston. | ||

| + | * (5) Gordon, T.J. 2009. ''The Delphi Method.'' Futures Research Methodology V 3.0. | ||

| + | * (6) Hallowell, M.R. Gambatese, J.A. 2010. ''Qualitative Research: Application of the Delphi method to CEM Research''. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 136(1). 99-107. | ||

| + | * (7) Boulkedid et al. 2011. ''Using and Reporting the Delphi Method for Selecting Healthcare Quality Indicators: A Systematic Review.'' PLoS ONE 6(6). 1-9. | ||

| − | + | ---- | |

| + | [[Category:Qualitative]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Quantitative]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Inductive]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Deductive]] | ||

| + | [[Category:System]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Future]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Methods]] | ||

| − | [[ | + | The [[Table_of_Contributors| author]] of this entry is Christopher Franz. |

Latest revision as of 13:46, 7 March 2024

Quantitative - Qualitative

Deductive - Inductive

Individual - System - Global

Past - Present - Future

In short: The Delphi Method is an interactive form of data gathering in which expert opinions are summarized and consensus is facilitated.

Contents

Background

The Delphi method originates from work at RAND Corporation, a US think-tank that advises the US military, in the late 1940s and 1950s (2, 3, 5). RAND developed "Project Delphi" as a mean of obtaining "(...) the most reliable consensus of opinion of a group of experts." (Dalkey & Helmer 1963, p.1). At the time, the alternative - extensive gathering and analysis of quantitative data as a basis for forecasting and deliberating on future issues - was not technologically feasible (4, 5). Instead, experts were invited and asked for their opinions - and Delphi was born (see (1)).

In 1964, a RAND report from Gordon & Helmer brought the method to attention for a wider audience outside the military defense field (4, 5). Subsequently, Delphi became a prominent method in technological forecasting; it was also adapted in management; in fields such as drug policy, education, urban planning; and applied in order to understand economic and social phenomena (2, 4, 5). An important field today is the healthcare sector (7). While during the first decade of its use the Delphi method was mostly about forecasting future scenarios, a second form was developed later that focused on concept & framework development (3).

Delphi was first applied in these non-scientific fields before it reached academia (4). Here, it can be a beneficial method to identify topics, questions, terminologies, constructs or theoretical perspectives for research endeavours (3).

What the method does

The Delphi method is "(...) a systematic and interactive research technique for obtaining the judgment of a panel of independent experts on a specific topics" (Hallowell & Gambatese 2010, p.99). It is used "(...) to obtain, exchange, and develop informed opinion on a particular topic" and shall provide "(...) a constructive forum in which consensus may occur" (Rayens & Hahn 2000, p.309). Put simply, experts on a topic are gathered and asked in a systematic process what they think about the future, until consensus is found.

The Delphi procedure

A Delphi process typically undergoes four phases (see (4), (6)):

1. A group of experts / stakeholders on a specific issue is identified and invited as participants for the Delphi. These participants represent different backgrounds: academics, government and non-government officials as wel, as practitioners. They should have a diverse set of perspectives and profound knowledge on the discussed issues. They may be grouped based on their organizations, skills, disciplines or qualifications (3). Their number typically ranges from 10 up to 30, depending on the complexity of the issue (2, 3, 5, 6).

The researchers then develop a questionnaire. It is informed by previous research as well as input from external experts (not the participants) who are asked to contribute knowledge and potential questions on the pertinent issue (2, 5). The amount of consultation depends on the expertise of the researchers on the respective issue (2).

2. The questionnaire is used to ask for the participants' opinions and positions related to the underlying issue. The questions often take a 'ranking-type' (3): they ask about the likelihood of potential future situations, the desirability of certain goals, the importance of specific issues and the feasibility of potential policy options. Participants may be asked to rank the answer options, e.g. from least to most desirable, least to most feasible etc. (2). Participants may also be asked yes/no questions, or to provide an estimate as a number. They can provide further information on their answers in written form. (8)

The questioning is most commonly conducted in form of a questionnaire but has more recently also been realized as individual, group, phone or digital interview sessions (2, 5). Digital questioning allows for real-time assessments of the answers and thus a quicker process. However, a step-by-step procedure provides more time for the researchers to analyze the responses (4).

3. After the first round, the participants' answers are analyzed both in terms of tendency and variability. The questionnaire is adapted to the new insights: questions that already indicated consensus on a specific aspect of the issue are abandoned while disagreements are further included. 'Consensus' may be defined based on a certain percentage of participants agreeing to one option, the median of the responses or a degree of standard deviation, among other definitions (2, 5, 6, 7). New questions may be added to the questionnaire and existing questions may be rephrased based on the first set of answers (4).

Next, the experts are again asked for their opinions on the newly adapted set of questions. This time, the summarized but - this is important - anonymous group results from the first round are communicated to them. This feedback is crucial in the Delphi method. It incentivizes the participants to revise their previous responses based on their new knowledge on the group's positions and thus facilitates consensus. The participants may also provide reasons for their positions (5, 6). Again, the results are analyzed. The process continues in several rounds (typically 2-5) until a satisfactory degree of consensus among all participants is reached (2-6).

4. Finally, the results of the process are summarized and evaluated for all participants (4).

Strengths & Challenges

The literature indicates a variety of benefits that the Delphi method offers.

- Delphi originally emerged due to a lack of data that would have been necessary for traditional forecasting methods. To this day, such a lack of empirical data or theoretical foundations to approach a problem remains a reason to choose Delphi. Delphi may also be an appropriate choice if the collective subjective judgment by the experts is beneficial to the problem-solving process (2, 4, 5, 6).

- Delphi can be used as a form of group counseling when other forms, such as face-to-face interactions between multiple stakeholders, are not feasible or even detrimental to the process due to counterproductive group dynamics (4, 5).

- The value of the Delphi method is that it reveals clearly those ideas that are the reason for disagreements between stakeholders, and those that are consensual (5).

- Delphi can be "(...) a highly motivating experience for participants" (Rayens & Hahn 2000, p.309) due to the feedback on the group's opinions that is provided in subsequent questioning stages.

- The Delphi method with its feedback characteristic has advantages over direct confrontation of the experts, which "(...) all too often induces the hasty formulation of preconceived notions, an inclination to close one's mind to novel ideas, a tendency to defend a stand once taken, or, alternatively and sometimes alternately, a predisposition to be swayed by persuasively stated opinions of others." (Okoli & Pawlowski 2004, p.2, after Dalkey & Helmer)

- Additionally, Delphi provides several advantages over traditional surveys:

- Studies have shown that averages of group responses are superior to averages of individual responses. (3)

- Non-response and drop-out of participants is low in Delphi processes. (3)

- The availability of the experts involved allows for the researchers to (a) get their precognitions on the issue verified by the participating experts and to (b) gain further qualitative data after the Delphi process. (3)

However, several potential pitfalls and challenges may arise during the Delphi process:

- Delphi should not be used as a surrogate for every other type of communication - it is not feasible for every issue (4, 5, 6).

- A specific Delphi format that was useful in one study must not work as well in another context. Instead, the process must be adapted to the research design and underlying problem (4).

- The proper selection of participating experts constitutes a major challenge for Delphi processes (3, 4, 5, 6). In addition, the researchers should be aware that any expert is likely to forecast based on their specific sub-system perspective and might neglect other factors (4).

- The monitor (= researcher) must not impose their own preconceptions upon the respondents when developing the questionnaire but be open for contributions from the participants. The questions should be concise and understandable and should not incentivise the participant to "get the job over with" (Linstone & Turoff 1975, p.568; 5).

- Diverse forms of bias might occur on the part of the participants that need to be anticipated by the researcher. These include discount of the future, over-optimism / over-pessimism, misinterpretations with regard to the complexity and uncertainty involved in forecasting the future as well as other forms of bias that may be imposed through the feedback process (4, 6).

- The responses must be adequately summarized, analyzed and presented to the participants (see the variety of measures for 'consensus' in What the method does)). "Agreement about a recommendation, future event, or potential decision does not disclose whether the individuals agreeing did so for the same underlying reasons. Failure to pursue these reasons can lead to dangerously false results." (Linstone & Turoff 1975, p.568).

- Disagreements between participants should be explored instead of being ignored so that the final consensus is not artificial (4).

- The participants should be recompensated for their demanding task (4)

Normativity

Connectedness / nestedness

- While Delphi is a common forecasting method, backcasting methods (such as Visioning) or Scenario Planning may also be applied in order to evaluate potential future scenarios without tapping into some of the issues associated with forecasting (see more in the Visioning entry)

- Delphi, and the conceptual insights gathered during the process, can be a starting point for subsequent research processes.

- Delphi can be combined with qualitative or quantitative methods beforehand (to gain deeper insights into the problem to be discussed) and afterwards (to gather further data).

Everything normative related to this method

- The Delphi method is highly normative because it revolves around the subjective opinions of stakeholders.

- The selection of the participating experts is a normative endeavour and must be done carefully so as to ensure a variety of perspectives.

- Delphi is an instrument of transdisciplinary research that may be used both to find potential policy options as well as to further academic proceedings. Normativity is deeply rooted in this connection between academia and the 'real-world'.

Outlook

Open questions

- The diverse fields in which the Delphi method was applied has diversified and thus potentially confounded its methodological homogeneity, raising the need for a more comparable application and reporting of the method (6, 7)

An exemplary study

In their 2014 publication, Kauko & Palmroos present their results from a Delphi process with financial experts in Finland. They held a Delphi session with five individuals from the Bank of Finland, and the Financial Supervisory Authority of Finland, each. Every individual was anonymized with a self-chosen pseudonym so that the researchers could track the development of their responses. The participants were asked questions in a questionnaire that revolved around the close future of domestic financial markets. Specifically, the participants were asked to numerically forecast 15 different variables (e.g. stock market turnover, interest in corporate loans, banks' foreign net assets etc.) with simple point estimates. These variables were chosen to "fall within the field of expertise of the respondents, and at the same time be as independent of each other as possible." (p.316). The participants were provided with information on the past developments of each of these variables.

The researchers decided to go with three rounds until consensus should be reached. For the first round, questionnaires were distributed by mail, and the participants had one week to answer them. The second and third round were held on the same day after this one-week period. The responses from the respective previous round were re-distributed to the participants (each individual answer including additional comments, as well as the group average and the median for each variable). The participants were asked to consider this information, and answer all 15 questions - i.e., forecast all 15 variables - again.

After the third round, the participants were additionally asked to fill out survey questions on a 1-5 Likert Scale about how reliable their considered their own forecasts, and how much attention they had paid to the others' forecasts and comments when these were re-distributed, both regarding each variable individually. This was done to better understand each individual's thought process.

The forecasting results from the Delphi process could be verified or falsified with the real developments over the next months and years, so that the researchers were able to check whether the responses actually got better during the Delphi process. They found that the individual responses did indeed converge over the Delphi process, and that the "Delphi group improved between rounds 1 and 3 in 13 of the questions." (p.320). They also found that "[d]isagreeing with the rest of the group increased the probability of adopting a new opinion, which was usually an improvement" (p.322) and that the Delphi process "clearly outperformed simple trend extrapolations based on the assumption that the growth rates observed in the past will continue in the future", which they had calculated prior to the Delphi (p.324). Based on the post-Delphi survey answers, and the results for the 15 variables, the researchers further inferred that "paying attention to each others' answers made the forecasts more accurate" (p.320), and that the participants were well able to assess the accuracy of their own estimates. The researchers calculated many more measures and a comparison to a non-Delphi forecasting round, which you can read more about in the publication. Overall, this example shows that the Delphi method works in that it leads to more accurate results over time, and that the process itself helps individuals better forecast than traditional forecasts would.

Key Publications

- Linstone, H. Turoff, M. 1975. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. Addison-Wesley, Boston.

An extensive description of the characteristics, history, pitfalls and philosophy behind the Delphi method.

- Dalkey, N. Helmer, O. 1963. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management Science 9(3). 458-467.

The original document illustrating the first usage of the Delphi method at RAND.

- Gordon, T.J. Helmer, O. 1964. Report on a long-range forecasting study. RAND document P-2982.

The report that popularized Delphi outside of the military defense field.

References

- (1) Dalkey, N. Helmer, O. 1963. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management Science 9(3). 458-467.

- (2) Rayens, M.K. Hahn, E.J. 2000. Building Consensus Using the Policy Delphi Method. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice 1(4). 308-315.

- (3) Okoli, C. Pawlowski, S.D. 2004. The Delphi Method as a Research Tool: An Example, Design Considerations and Applications. Information & Management 42(1). 15-29.

- (4) Linstone, H. Turoff, M. 1975. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. Addison-Wesley, Boston.

- (5) Gordon, T.J. 2009. The Delphi Method. Futures Research Methodology V 3.0.

- (6) Hallowell, M.R. Gambatese, J.A. 2010. Qualitative Research: Application of the Delphi method to CEM Research. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 136(1). 99-107.

- (7) Boulkedid et al. 2011. Using and Reporting the Delphi Method for Selecting Healthcare Quality Indicators: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 6(6). 1-9.

The author of this entry is Christopher Franz.