Survey Research

Quantitative - Qualitative

Deductive - Inductive

Individual - System - Global

Past - Present - Future

In short: Surveys are highly systematized and structured forms of data gathering through written or oral questioning of humans. This entry includes Structured Interviews and Questionnaires as forms of Survey Research. For more Interview forms, and more on Interview methodology in general, please refer to the Interview overview page.

Contents

Background

Surveys were first applied in research in the field of sociology in the 1930s and 1940s (1, 2). Back then, the sociologist Paul Lazarsfeld used surveys to study the effects that the radio had on the public's political opinions in the US (1). Today, surveys are considered a widespread quantitative method in the social sciences (1).

What the method does

A survey, i.e. survey research, is a set of research methods which uses “standardized questionnaires or interviews to collect data about people and their preferences, thoughts, and behaviors in a systematic manner” (Bhattacherjee 2012, p. 73; 2). Surveys are commonly applied in “descriptive, exploratory, or explanatory research” (Bhattacherjee 2012, p. 73). They are used to “investigate social phenomena and understand society” (Brenner 2020, p. 2) as well as “to inform knowledge, challenge existing assumptions, and shape policies” (Gideon 2012, p. 3).

Types of Surveys

Survey research can be divided into an 'exploratory' and an 'explanatory' type (8). Explanatory survey research, which is typically seen as more important, “is devoted to finding causal relationships among variables. It does so from theory-based expectations on how and why variables should be related. […] Results then are interpreted and in turn contribute to theory development.” (Malhotra & Grover 1998, p. 409). By comparison, exploratory survey research is an inductive approach and is not based on theories or models. It rather aims at understanding a topic or measuring a concept better. This type can thus be especially helpful in early research stages and can prepare the ground for explanatory survey research and hence for studying the variables in-depth. (8). Even though more and more researchers follow an inductive approach by e.g. applying exploratory survey research to contribute to theory development, the deductive explanatory approach still predominates survey research (88).

Survey types can further be distinguished according to their mode, their target population, the data they collect, and the number or duration of data collection activities, among other variables (3). The survey mode, i.e. how the information is collected, exists in two types: questionnaire surveys and structured interview surveys. Questionnaires, also called self-completion surveys, are filled out independently by the participants either online or on a piece of paper e.g., after having received them by mail or handed out on the street. By comparison, an interview survey has an interviewer present the questions of the questionnaire to the participant, either in person (face-to-face), via the telephone or in the context of a focus group (1; 3). Interview surveys might be the mode of choice “when the survey is long [...] or when additional information has to be collected” (Gideon 2012, p. 14).

Surveys can also be distinguished based on the times or duration of data collection (3). Surveys which involve a single data collection activity are called 'cross-sections'. Surveys that are repeated regularly by addressing a different sample of the target population every time are called 'repeated cross-section' or 'longitudinal' surveys. Here, the latter term emphasizes the survey’s comparative nature over time. A survey that targets the same sample with each regular repetition is called a 'longitudinal panel' and allows for examining “change at an individual level” (Gideon 2012, p. 16).

Sampling for Survey Research

When planning a survey, a population of interest – the target population – needs to be identified, of which only a proportion – the sample – is asked to participate (3). A survey is used “to obtain a composite profile of the population” (Gideon, 2012, p. 8), but neither intends “to describe the particular individuals who, by chance, are part of the sample” (Gideon 2012, p. 8), nor covers the entire target population as is done in a census (3). The latter is often not possible due to a lack of feasibility and funding (1).

The sample chosen for the survey should represent the target population so that generalizations and “statistical inferences about that population” (Bhattacherjee 2012, p. 65) can be made based on the results of the survey (1). To ensure the representativeness of a sample, different strategies can be applied, including simple random sampling, stratified sampling, and cluster sampling, among others (3).

When determining the sample, a bigger sample size is almost always better. A bigger size will reduce skewness of the sample, and it takes a sufficiently large sample to reach a normal distribution within the sample. Of course, you cannot sample endlessly, as organisational and financial restrictions limit the possible amount of survey respondents: you cannot hand out surveys to bypassers on the street for years, and you will never reach everyone in your target population via the Internet. Also, the adequate sample size for a survey depends on many different factors, such as the study objective and the sampling method. In case of simple random sampling, for example, the heterogeneity of the target population plays a role, as does the confidence interval you aim for, and how you want to analyze your data (e.g. analysis by subgroups, type of statistical analysis). Contrary to popular belief, the size of the target population is of little or no relevance unless the target population is relatively small, i.e. only consists of a few thousand people (3). Taking this multitude of factors into account, sample size calculators on the Internet, such as this one, can help to get an idea of which sample size might be suitable for your study. Keep in mind that when determining the sample size, the estimated response rate needs to be accounted for as well, so you most likely need to invite more people for the survey than the calculated sample size indicates (see below; 3).

Moreover, the unit of analysis which the information is collected on needs to be defined to adequately sample, and then be consistently addressed by each question in the survey (8). Here, the decisive factor is not the fact that the person who responds is an individual, but the unit that the responding person represents (8). This unit can be the individual itself as well as its “work group, project, function, organization or even industry” (Malhotra & Grover, 1998, p. 410). It is crucial that the participants of a survey suit the unit of analysis, i.e. have sufficient insight into the topic and thus unit under study (8). To this end, while survey research works with individuals in the first place, it is a system-level investigation of societal groups, organizations etc.

For more on sampling in Survey Research, please refer to Bhattacherjee (2012) who dedicates an entire chapter on this topic, as well as to the entry on Sampling for Interviews.

Survey Design

Survey research is commonly used as a quantitative method (8) for studies “that primarily aim at describing numerical distributions of variables (e.g. prevalence rates) in the population” (Jansen 2010, The Qualitative Survey section, para. 4). This can be done for survey responses that are qualitative in nature (nominal, ordinal) as well as for quantitative responses (see Data formats below). However, survey responses can also be analyzed qualitatively, making it a qualitative method which “does not aim at establishing frequencies, means or other parameters but at determining the diversity of some topic of interest within a given population. This type of survey does not count the number of people with the same characteristic (value of variable) but it establishes the meaningful variation (relevant dimensions and values) within that population.” (Jansen 2010, The Qualitative Survey section, paragraph 5). The differentiation of both approaches is most relevant when it comes to the subsequent analysis. Check out the wiki entry on quantitative and qualitative [content analysis](https://sustainabilitymethods.org/index.php/Content_Analysis) to learn more about the analysis of survey data.

In any case, an important aspect of survey research is the highly standardized procedure when collecting information, which means “that every individual is asked the same questions in more or less the same way” (Gideon 2012, p. 8). The design of a survey is moreover highly dependent on its purpose e.g., how fast the data need to be collected, how precise the results should be or if responses must be comparable between different target populations.

When designing a survey, different types of questions can be included (3). Note that the questions asked in the survey (questionnaire items) are not the same as the ones you aim to answer with your research (internal questions). The internal questions usually have to be broken down into several questions to encompass the entirety of the research question or reformulated to be comprehensible for the survey participants and to produce answers suitable for analysis (65).

Generally, one distinguishes between 'objective' and 'subjective' questions as well as unstructured (also called 'open-ended') and structured (also called 'closed') questions. Objective questions refer to topics such as one’s employment, living situation, education level, or health condition. Subjective questions correspond to personal opinions and values (3).

Open-ended questions require the respondents to formulate their answer freely and “in their own words” (Krosnick 1999, p. 543). This is especially “suitable for exploratory, interviewer-led surveys” (Kasunic 2005, p. 43), as its response format is less restrictive, but comes with its own challenges (see “Strengths & Challenges”).

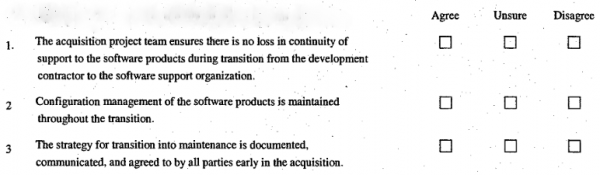

The more common closed questions provide participants with a set of prescribed answer options. These questions can have ordered, ordinal answer options in form of a “graduated scale along some single dimension of opinion or behavior” (Kasunic 2005, p. 42). Typically, this is done by using a 5-point Likert Scale. However, these answer options can also have 3-point answer options (e.g. Yes, Maybe, No) or be dichotomous (binary), e.g. yes/no, agree/disagree (Bhattacherjee 2012, p. 75; Kasunic 2005, p. 44). When using ordinal scales, an appropriate range, i.e. number of answer options, needs to be chosen so that participants can find an option that suits their perspective (6).

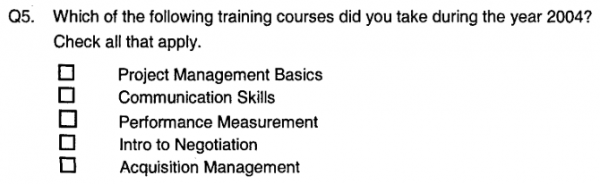

Closed questions can also offer unordered answer options in form of nominal data, like distinct categories in a list (6). In this case, the researcher can choose how many answers can be checked by the respondents for each question (6). Further, closed questions can also have a continuous response format, “where respondents enter a continuous (ratio-scaled) value with a meaningful zero point, such as their age or tenure in a firm. These responses generally tend to be of the fill-in-the blanks type.” (Bhattacherjee 2012, p. 75).

Examples for different question types and response formats (including Likert-type scales) are offered by Bhattacherjee (2012) on page 75 and by Kasunic (2005) in section 4.2.1 and appendix D. Additionally, the wiki entry on Data formats can help you understand the different response formats in surveys better.

Besides the response format, further aspects regarding the question design include the number and order of questions as well as corresponding answers, the wording and “the context in which the question is asked” (Gideon 2012, p. 30). Moreover, the “introduction, framing, and questionnaire designs” (Gideon 2012, p. 30) need to be thoroughly devised to appeal to the target group and avoid biases. All these decisions can influence the survey results in terms of the “response rate, response accuracy, and response quality” (see below; Gideon 2012 p. 30).

Pretesting a Survey

Before the actual conduction of a survey, it is usually pretested. The pretest is designated to identify items in the survey which are biasing, difficult to understand or misconceived by the participants e.g., because of their ambiguity (1; 3; 7). Further, the validity of the survey items can be evaluated through a pretest (3). The people participating in the pretest are ideally drawn from the target population of the study, while time constraints or other limitations sometimes only allow for resorting to a convenience sample (1; 3). After the pretest, necessary adaptations in the survey are made (1).

Different pretesting methods exist which “focus on different aspects of the survey data collection process and differ in terms of the kinds of problems they detect, as well as in the reliability with which they detect these problems” (Krosnick 1999, p. 542). Cognitive pretesting – also called “’thinkaloud’ interviews” (Gideon 2012, p. 30) – is one such method. It “involves asking respondents to ‘think aloud’ while answering questions, verbalizing whatever comes to mind as they formulate responses” (Krosnick 1999, p. 542). By getting to know the cognitive processes behind making sense of and answering the survey questions, “confusion and misunderstandings can readily be identified” (Krosnick 1999, p. 542).

Response Rate and Data Quality of a Survey

A high response rate is always desirable when conducting a survey. A good sampling strategy won't do much if no one answers to the survey. Also, a stratified sampling strategy won't work if there are skewed responses. There are multiple strategies that can be applied to increase the response rate. First, the chosen topic of the survey should be of interest or relevance for the target population under study. Then, “pre-notification letters, multiple contact attempts, multi-mode approaches, the use of incentives, and customized survey introductions” (Gideon 2012, p. 31) are further strategies which can help increase the response rate. In case of interview surveys, a thorough training of the interviewers can be effective in motivating the interviewees to share their answers openly (3).

The response quality is influenced by the personal interest and intrinsic motivation of the participants, too (3). Unwilling respondents who want to go through the survey as quickly as possible might “engage in satisficing, i.e. choosing the answer that requires least thought” (Gideon, 2012, p. 140). Further, the attention span and motivation level of the participants might decrease over the course of the survey, which is referred to as respondent fatigue and negatively affects the data quality (108). Indicators for respondent fatigue and a limited response quality in general are an increased number of “don’t know”-answers, short and superficial responses to open-ended questions, “’straight-line’ responding (i.e. choosing answers down the same column on a page)” and ending the survey prematurely (3; 10).

Of course, a good survey is also measured by its validity (the degree to which it has measures what it purports to measure) and reliability (the degree to which comparable results could be reproduced under similar conditions) (3).

Strengths & Challenges

Strengths

Surveys – especially self-completion questionnaires – are often associated with economical advantages such as savings in time, effort, and cost when compared to more open interviews (1; 3). Further, (digital) surveys allow to collect information which would otherwise be difficult to observe, e.g. because of the size or remoteness of the target population or because of the type of data, such as subjective beliefs or personal information (1). To this end, survey research allows for larger samples compared to more qualitative open or semi-structured interviews. Furthermore, “large sample surveys may allow detection of small effects even while analyzing multiple variables, and depending on the survey design, may also allow comparative analysis of population subgroups” (Bhattacherjee 2012, p. 73).

A strength of questionnaire surveys and the reason why they are sometimes preferred by survey participants compared to interview surveys is their “unobtrusive nature and the ability to respond at one’s convenience” (Bhattacherjee, 2012, p. 73). Interview surveys, by contrast, make it possible to reach out to difficult-to-reach target populations e.g., homeless people or illegal immigrants (1).

Challenges

Among the biggest challenges related to survey methods are the multitude of biases that can occur, as those biases can “invalidate some of the inferences derived” (Bhattacherjee, 2012, p. 80) from the collected data. Those biases include, among others, non-response bias, sampling bias, social desirability bias, recall bias, and common method bias. While the different biases are discussed briefly in the Wiki article Bias in Interviews, you can find a more detailed explanation of those biases as well as strategies on how to overcome them in Bhattacherjee (2012).

Further challenges in survey research include the avoidance of respondent fatigue and the assurance of the validity and reliability of the gathered data and analyzed results (3; 10).

A number of challenges also come with the increased reliance on the Internet for the implementation of surveys (3), such as safeguarding data protection (4). Participants may also engage in Internet surveys only to receive a promised incentive at the end, which can “lead to […] false answers, answering too fast, giving the same answer repeatedly […], and getting multiple surveys completed by the same respondent” (Hays et al. 2015, p. 688). Ways to avoid such incidents are e.g., the provision of feedback to the respondents while they are filling out the survey by pointing out that they seem to be rushing or giving the same answer for many questions in a row, or the verification of their e-mail and IP address to “to ensure the identities of individuals that join and to minimize duplicate representation on the panel” (Hays et al. 2015, p. 688). Moreover, before analyzing the survey results, those survey submissions can be excluded which exceed a certain number of missing answers, which were submitted faster than a minimum time span defined, or which contain identical answers for a defined number of consecutive questions (4).

Furthermore, the use of each question type comes with challenges. For example, “a closed-ended question can only be used effectively if its answer choices are comprehensive, and this is difficult to assure” (Krosnick 1999, p. 544). Also, “respondents tend to confine their answers to the choices offered” (Krosnick 1999, p. 544) instead of adding their own response if no fitting answer option is listed. Including open-ended questions in a survey can lead to a time-consuming analysis, as the individual answers need to be sorted and interpreted. Further, the interpretation of the open responses – especially in self-completed surveys – and thus the assurance of validity is considered challenging as no follow-up questions can be asked (6). Further, “meaningful variables for statistical analysis” (Kasunic 2005, p. 40) can hardly be extracted from open-ended answers.

Normativity

Designing and conducting a survey entails several ethical challenges (3). One main concern is the avoidance of biases. First, the answers of the survey participants must not be influenced to fit the researchers’ hypothesis or a research client’s desired outcome e.g., by formulating or presenting the questions in a certain way. Second, the results need to be generated and presented to “accurately reflect the information provided by respondents” (Gideon 2012, p. 23). In addition, the data and response quality should be critically reflected on during and after data collection (3). Furthermore, data privacy as well as the protection of the survey participants from any other type of abuse needs to be ensured (3).

Outlook

Gideon (2012) points out that with regard to quality control of survey research, many sources of error and bias have not received enough attention in the past. The author highlights that (early career) researchers have placed much focus on sampling errors, which are comparatively easy to detect and resolved by adapting the sample size. However, non-sampling errors, such as response and non-response errors and their underlying challenges, have often been insufficiently dealt with, even though their negative impact on the survey quality and results is substantial. Such errors can occur at several stages in the survey research process and are usually characterized by a higher complexity than sampling errors; they cannot be resolved by simply increasing the sample size or by ensuring the representativeness of the sample (3). Therefore, Gideon (2012) calls for the total survey error – which takes sampling as well as non-sampling errors into account – to be “the dominant paradigm for developing, analyzing, and understanding surveys and their results” (Gideon 2012, p. 4) in the future.

According to Miller (2017), one main challenge for future survey research consists in sustaining sufficient response rates. As more and more people have declined their participation when invited to a survey during the past years, both the risk of nonresponse bias and the costs allocated for participant recruitment increase (9). How well survey research can adapt to further changes in communication technology (e.g. through the Internet) will play an important role in this regard (9). However, more research on the causes of and possible solutions for the decline in survey participation needs to be conducted (9).

Another development which is likely to affect the use of survey research and its results in the future is the blending of data, i.e. the combination of different data sources (9). According to Miller (2017), “blending survey data with other forms of information offers promising outcomes and technical challenges” (p. 210) at the same time.

Despite the challenges survey research might face during the decades to come, Miller (2017) concludes that survey research will continue to be relevant by providing important (statistical) information for academia as well as policymaking.

An exemplary study

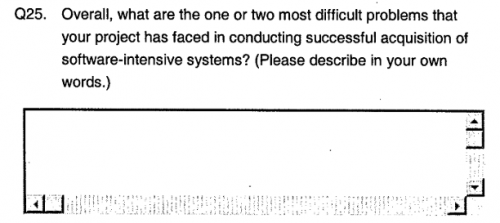

In their 2007 publication, Cotton et al. (see References) used a digital survey to explore lecturers’ understanding of and attitudes towards sustainable development and their beliefs about incorporating sustainable development into the higher education curriculum. The study was conducted at the University of Plymouth, where lecturers from different disciplines were invited to participate.

The methodical approach consisted of two stages, the first one being an online questionnaire survey and the second one being in-depth semi-structured interviews. The questionnaire survey had two main objectives. First, it was used “to establish baseline data on support for sustainable development across the university’s faculties and provide lines of enquiry for further research” (p. 584). Second, it should allow for a systematic selection of survey participants who could be interviewed in the second stage of the research by calling for volunteers.

The questionnaire contained both closed and open-ended questions, where the latter question type was used “to complement quantitative data where it was felt useful to elicit more detailed information” (p. 584). The software SPSS was used for the analysis of the quantitative data, while Pearson’s Chi-Square test functioned as the “test for association between certain variables, with significance accepted where p < 0.05” (p. 584). The analysis of the qualitative data was conducted “using thematic analysis employing the constant comparative method (Silverman, 2005)” (p. 584).

The questionnaire was repeatedly pre-tested and revised before it was piloted with researchers and lecturers from different fields. For the pilot test, two versions of the questionnaire were chosen which differed with regard to their terminology. While one version referred to “sustainability”, the other version used the term “sustainable development”. This was done to find out which of the two terms was understood better by the potential respondents and resulted in the use of “sustainable development” for the final questionnaire version. However, as lecturers from different disciplines and with a different background knowledge on the topic were targeted with the survey, unfamiliarity with different terminologies was still difficult to avoid.

The recruitment of participants for the online questionnaire was done via e-mail to the academic staff of the university, which included a link to the online survey that was accessible for a month. With 328 responses received, the response rate consisted of 29 percent which the authors consider comparable with similar online surveys. Moreover, the respondents were found to be “broadly representative of university lecturers as a whole in terms of gender, age and contract status (full/part time)” (p. 585). However, the authors do not discount “the probability that those who responded had a better understanding of, or perhaps stronger opinions on, sustainable development than non-respondents” (p. 585), which is of particular relevance with regard to the interpretation of results.

The authors present their findings in three main sections: (1) Understandings of sustainable development, (2) Attitudes towards sustainable development, and (3) Beliefs about incorporating sustainable development into the higher education curriculum.

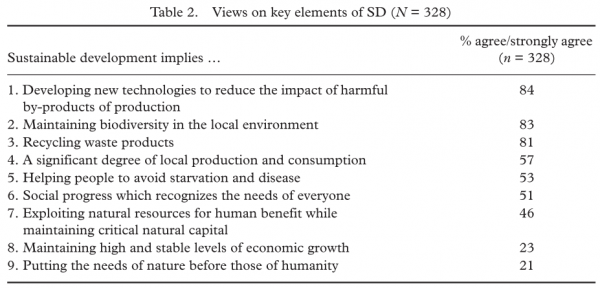

The following table (p. 586) shows the results for the lecturers’ interpretation of the concept of sustainable development, i.e. the percentage of respondents who “agree” and “strongly agree” to the listed propositions. For this closed-ended question, a five-point Likert scale was used. The participants further had the possibility to give an open-ended response to this question. While many viewed the somewhat oversimplified tickbox definitions as problematic and elaborated on their opinions further, “others admitted that they struggled to make sense of the options offered” (p. 587). This shows the varying levels of knowledge in the group and moreover indicates “the immense difficulties of designing a questionnaire to examine views on a multifaceted and contested concept like sustainable development” (p. 587).

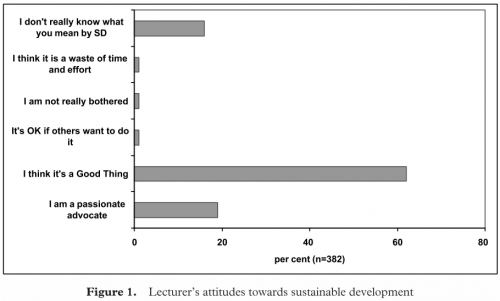

The next diagram (p. 588) presents the responses to the question on the lecturers’ attitudes towards sustainable development. While the quantitative data shows a “fairly strong agreement amongst respondents in support of sustainable development” (p. 588), the authors acknowledge the challenges when it comes to the interpretation of “such a general statement” (p. 588): “[W]ere respondents commenting favourably on the idea of sustainable development per se, or was this simply a convenient proxy for a range of environmental, social and economic concerns?” (p. 588).

Regarding the lecturers’ beliefs about incorporating sustainable development into the higher education curriculum, “[o]ver 50% of respondents predicted including elements of sustainable development in their teaching in the coming year” (p. 589). The authors point out that this number can be the result of overreporting, as the questionnaire is self-reported and does not observe actual behaviors and actions. In addition, the authors clarify that “what constitutes ESD remains a matter of personal interpretation, and may include changes to either content or process (approaches to teaching the subject)” (p. 589), which further complicates the interpretation of the quantitative data.

For more on this study and the study’s findings, please refer to the References.

Key Publications

Bhattacherjee, A. 2012. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- The chapter on survey research includes an own section on questionnaire surveys and interview surveys each and gives detailed insights into different types of biases in survey research.

Gideon, L. 2012. Handbook of survey methodology for the social sciences. Springer.

- This handbook provides detailed insights on how to do survey research and gives advice along the entire research process.

Kasunic, M. 2005. Designing an Effective Survey. Available at https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA441817.pdf.

- This publication offers hands-on advice and a step-by-step instructions on how to do survey research with questionnaires.

References

(1) Bhattacherjee, A. 2012. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

(2) Brenner, P. S. (Ed.). 2020. Frontiers in sociology and social research: Volume 4. Understanding survey methodology: Sociological theory and applications. Springer.

(3) Gideon, L. 2012. Handbook of survey methodology for the social sciences. Springer.

(4) Hays, R. D., Liu, H., & Kapteyn, A. 2015. Use of Internet panels to conduct surveys. Behavior Research Methods 47(3), 685–690.

(5) Jansen, H. 2010. The Logic of Qualitative Survey Research and its Position in the Field of Social Research Methods. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research 11 (2). Visualising Migration and Social Division: Insights From Social Sciences and the Visual Arts.

(6) Kasunic, M. 2005. Designing an Effective Survey. Available here.

(7) Krosnick, J. A. 1999. Survey Research. Annual Review of Psychology 50, 537–568.

(8) Malhotra, M. K., & Grover, V. 1998. An assessment of survey research in POM: from constructs to theory. Journal of Operations Management 16(4), 407–425.

(9) Miller, P. V. 2017. Is There a Future for Surveys? Public Opinion Quarterly 81(S1), 205–212.

(10) P. J. Lavrakas (Ed.) 2008. Respondent fatigue. Encyclopedia of survey research methods. SAGE.

(11) Cotton, D.R.E. Warren, M.F. Maiboroda, O. Bailey, I. 2007. Sustainable development, higher education and pedagogy: a study of lecturers' beliefs and attitudes. Environmental Education Research 13(5), 579-597.

The author of this entry is Fine Böttner.