Supply Chain Analysis

Quantitative - Qualitative

Deductive - Inductive

Individual - System - Global

Past - Present - Future

In short: Supply chain analysis is the systematic analysis of different stages in a production cycle.

Contents

Background

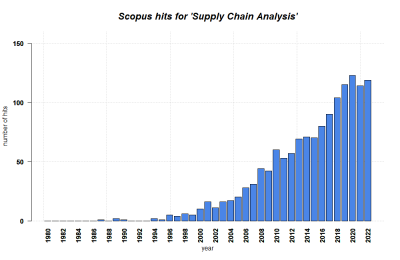

In the 1990s, the corporate view on logistical processes shifted due to changes in the manufacturing environment, including increasing costs, globalized markets, shrinking resources and more (1). Instead of a rather vertical, hierarchical understanding, logistical processes were seen as functional, integrated and important for managing a company. Thus, the framework of supply chains (and their analysis) emerged and initiated a new management discipline: supply chain management; including new corporate positions such as a firm's Supply Chain President. Different approaches of analyzing supply chains were created, investigating either physical flows of material, underlying organizational segments or supply chain processes, i.e. purchasing, sales etc. (9).

This last approach began to evolve in 1996 with the development of the SCOR (Supply Chain Operations Reference)-model by the Supply Chain Council (SCC), which aimed at standardizing the analysis and terminology of supply chain analyses (14) [Sürie & Wagner, p. 41]. This introduction for the first time provided a systematic and standardized framework for supply chain assessments.

During the time after the introduction of the SCOR model, each process within a supply chain was typically analyzed and studied individually. In modern SCAs, however, the supply chain is seen as a complex process and as an entity consisting of multiple parts. Recently, there have been more holistic, transformative approaches to supply chains and their performance, called 'closed-loop supply chain management'. Supply chains are called 'closed-loop' when they combine a traditional forward chain with reverse processes to recover products that then eventually re-enter the forward supply chain (11, p.247). This can be explained by the increasing wish to optimize a supply chain's performance and to include "reverse logistics" (meaning recycling and reusing of products) [1].

More recently, also, transdisciplinary research of supply chains, i.e. closed-loop SCM, has been emerging, creating new knowledge by enabling multiple forms of collaboration (inter-academic, management - academic, academic - non-academic (11). Disciplines that play a crucial role in this approach are: natural & engineering sciences, management sciences and the industry itself (11). Through collaboration and information exchange, innovation and collaborative optimization can be achieved (11). Especially for Corporate Sustainability (i.e. an implementation of sustainable strategic management into the core business to create value for stakeholders), the approach of Closed-loop SCM plays an important role (11).

What the method does

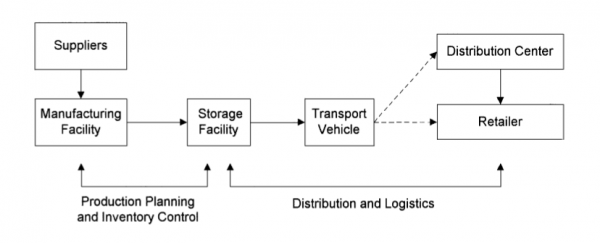

A supply chain can be defined as an "integrated manufacturing process wherein raw materials are converted into final products, then delivered to customers" [1, p. 282]. Supply chains combine production planning and inventory control processes as well as product distribution and logistical processes.

The analysis of an existing supply chain typically serves as the basis for an improvement process in an industrial or economic sector. The operations and processes along and within the supply chain are studied in detail, keeping both a strategic and operational view. The findings are put into an initial analytical model. These can be:

- deterministic (variables are known and specified),

- stochastic (at least one variable unknown; assumptions on its distribution are made),

- economic (relationship matrix of product and process specificity; capturing risks for respective buyer and supplier), or

- simulating (evaluating effects and effectiveness of strategies on supply chain and demand patterns; simulating improvement strategies),

depending on the input and objective of the analysis (1). Adaptations to the modeled supply chain can be made when the real-world supply chain changes and a development in its performance is observed over a long timespan [Sürie & Wagner, p. 37].

A supply chain analysis consists of two main tasks: the process modeling, meaning the abstraction of real-world processes into a model, and the performance measurement. The latter revolves around identifying metrics to measure a supply chain's success and economic performance (14)]. These tasks can be divided into more detailed steps as follows:

Process modelling

1. Identifying the most important processes in the supply chain, which typically include: customer relationship and service management, demand management, order fulfillment, manufacturing flow management, supplier relationship management, product development (commercialization) and lastly, returns management. These processes "can be traced best by the flow of materials and information flows" (14, p.39. Notably, not all processes are equally important in a given company or for a given product or service. Further, there might be interferences between different processes, so it is helpful to focus on these eight core processes and always keeping a strategic view on the supply chain (14, p.39).

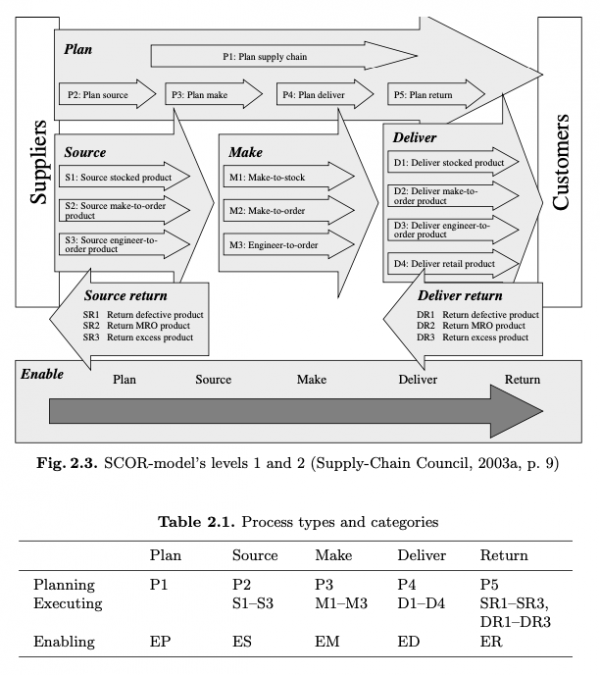

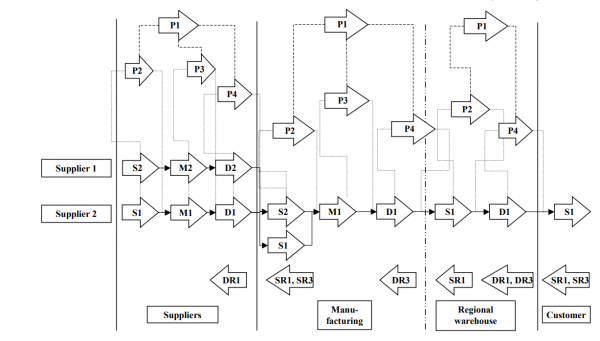

SCOR-models comprise three relevant hierarchical levels of standard processes in supply chains. With each level, the amount of detail in the analysis of the process (or interaction between supplier and customer) increases. Lower level processes can be arranged in higher levels. From the highest to lowest level, these levels are:

- Process types: on this level, the supply chain is arranged into plan, source, make, deliver, return (16, see visualisation below).

- Process categories: on this level, there are 26 categories in total as part of the process types. They can be split into the meta-categories planning, executing or enabling. (see visualisation below).

- The planning category describes the initial planning step to each process which entails the "allocation of resources to the expected demand" (14, p.43).

- The executing category can be understood as the moment of realizing and executing the planned processes, "triggered by planned or current demand" (14, p.43). Therefore, this category covers the supply chain from the source processes to the return processes.

- Processes in the enabling category support the other processes by providing the flow of information and process interrelations.

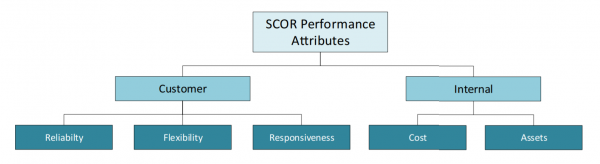

- Process elements: on the third level, the processes are decomposed by looking at specific input and output streams for each process and individual element. There exist detailed metrics that evaluate the "reliability, flexibility, responsiveness, cost and assets" (14, p.46) to help the analysis.

2. Tracing the flow of material (e.g. goods), information (e.g. purchase orders) and finances (e.g. payments) along the chronological sequence from the supplier to the customer, or reverse in case of returns (14). 3. Translating the observations into a standardized language, for example the process chain notation, which was developed by Kuhn in 1995 and allows for a hierarchical structuring of sub-processes. This prevents misconceptions, helps to structure the processes hierarchically and to focus on the most important processes (14). 4. Visualizing and modeling the supply chain processes by using standardized tools, e.g. ARIS. To this end, the aforementioned SCOR-model is still the most popular and widespread approach also for this step (14).

In short, the application of the SCOR model for the visualisation and modelling of supply chain processes entails:

4.1) defining the business unit that is to be analyzed. Such areas of business or a given company can be organization, sales, controlling or even a combination of key aspects in a successful supply.

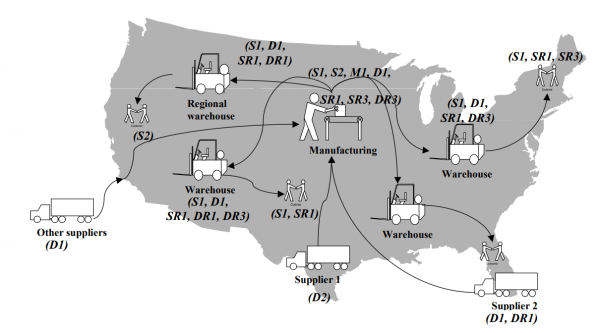

4.2) geographic placement and denomination of entities in supply chains. In global supply chains, suppliers and production steps can be highly dispersed, which is why it is important to map and indicate all relevant locations in the supply chain (14).

4.3) + 4.4) defining major material flows and visually connecting locations on the map with lines with regards to the specific process type ('source', 'make', 'deliver', 'return').

4.5) defining partial process chains. Here, a subchain/a chain is defined that follows only one specific product group. This serves the purpose of further breaking down the complex, interwoven material flows defined above.

4.6) Finally, drawing dashed lines for the process type 'plan', therefore illustrating execution and planning processes. Here, P2-P5 are the different planning process categories mentioned above (Figure 2.1) [Sürie & Wagner, p. 48].

4.7) Lastly, defining a 'top-level' planning process, i.e. a process that coordinates and connects two or more partial process chains. This may not be possible for every supply chain due to a lack of overarching processes.

Performance measurement

After the supply chain is modeled (based on the described processes), an SCA includes the measurement of the supply chain's unique performance. "A performance measure, or a set of performance measures, is used to determine the efficiency and/or effectiveness of an existing system, or to compare competing alternative systems" (1, p. 287). To do so, the most important metrics have to be defined and connected with the individual supply chain strategy and goal. Measures can be qualitative or quantitative and can be divided into more specific indicators (1, p. 287). These indicators are either informing (i.e. helpful for management and decision-making, comparing indicators with specific values), steering (i.e. guiding towards a set target/outcome) or controlling (i.e. helpful for supervising) (14).

There are different approaches to grouping and assessing key indicators for SCAs. One possible way to sort them is according to the following aspects:

- delivery performance: Indicators that are oriented on customers (expectations, reactions etc.) and surround the quality of customer service and ordering, as well as the timing of delivery (14).

- supply chain responsiveness: Indicators surrounding the quantified ability of adjustment to changes in the market. This is important because "[s]upply chains have to react to significant changes within an appropriate time frame to ensure their competitiveness" (14, p.55). For example, the number of days a supply chain needs to respond to an increase of x% in demand could be such an indicator.

- assets: Indicators dealing with asset (capital), revenue (sales/turnover), and/or transactions. In general, these indicators measure a company's asset efficiency but may vary across industries.

- inventories: Indicators analyzing the inventory. These can either focus on the age of the inventory (= the amount of time the product was stored/in stock), or on "the ratio of total material consumption per time period over the average inventory level of the same time period" (14, p.55). Increases and decreases in inventories are observed and connected to components such as costs or possible changes in value and demand. For the result to be as complete and objective as possible, a holistic view on the supply chain is of utmost importance (14). In supply chains with inflow and outflow processes, inventories (storage) are necessary - a fact often overlooked. Inventories have to be dealt with as an aspect that at the same time causes costs but also benefits (1, 14).

- costs: Financial indicators related to cost accounting. Other aspects of interest in this indicator category are productivity (employment value), product quality and problems regarding warranty (guarantee) costs (14).

- another possible indicator that is often considered important is productivity which can be measured by the ratio of revenue (i.e. in $) per labour time (i.e. in hours).

For further reading and a detailed list of performance measurement indicators, see Beamon (1998, see References).

With the process modelling and performance measurement done, the SCA is completed. Based on the resulting insights, the supply chain can then be managed (SCM = supply chain management), optimized and its performance can be improved. The SCM often pursues a specific aim, i.e. to generate more profit, to become more efficient, to adapt to new regulations or react to societal demands and become more sustainable or fair.

Role of SCA for Science

SCAs build the basis for any further management, modification and innovation of supply chains. They result in a visualized analysis of the current state of a supply chain. This has value for academic research in multiple disciplines: the results of an SCA can be used as a basis for surveys that aim at improving stakeholder relationships and economic success. They can be used for transformative scenario planning and the modeling of alternative supply chains. The results can further be compared to other existing SCAs, e.g. in a Meta-Analysis. This can be done to either optimize research frameworks and methodological approaches, to enable a more transparent insight into a company's supply chain and management decisions, or to test other hypotheses surrounding supply chains (14). Regarding the SCOR model, there are multiple new versions and applications, such as the GreenSCOR model, which tackles sustainable issues along supply chains and the shift towards corporate sustainability (7). This, too, opens new possibilities for research on supply chains.

Strengths & Challenges

- SCAs enable an overview on the supply chain as a whole. In a second step, they allow for adjustments that can make supply chains more profitable and efficient.

- In a more transformative thinking, supply chains can become fairer and more sustainable through SCAs. Considering the increasing legal demands for more transparent supply chains and corporate responsibility, this can be seen as a very important aspect for action-oriented science focussing on aspects of transparency, fair labor, resource efficiency and ethical business management etc.

- Most indicators for a supply chain and its performance are, since they need to be measurable and comparable (14). Non-quantitative () aspects are harder to quantify and are thus often neglected in the process. There are however some emerging approaches to a more qualitative analysis, i.e. the so-called model of sustainable supply chain management integration (SSCMI). With this, researchers try to embed qualitative and quantitative factors leading to an integration of sustainable standards (see 17, p. 221-223).

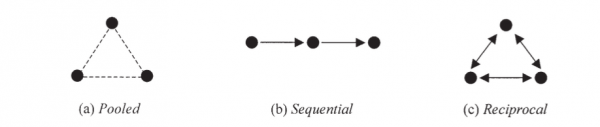

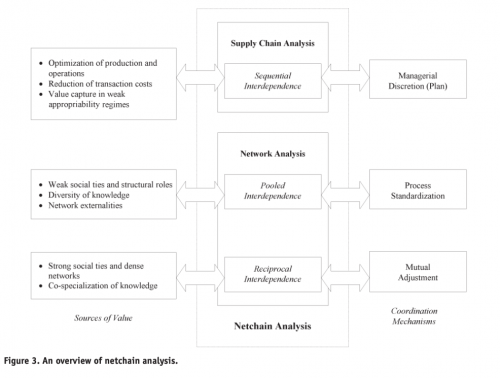

- Following Thompson (1967), there are three types of interdependencies, i.e. relational dependencies between entities in e.g. inter-organizational relations. SCAs cover only the sequential interdependencies, i.e. dependencies with serial structures where the decisions and activities of one supplier (or firm) influences those of the next firm. Thinking of a supply chain as a linear, chronological sequence, starting with a supplier and ending with a customer, the sequential interdependence seems fitting. This however leads to the other two types not being integrated. These are pooled interdependencies ("each individual in a group makes a discrete, well-defined contribution to a given task" (6, p. 11) and reciprocal interdependencies, which "involves simultaneous, ongoing relationships between parties in which each agent’s input is dependent on the others’ output and vice-versa" (6, p. 11). The implementation of the other interdependencies could however create new knowledge and offer new insights into the supply (value) chain.

- SCAs are additionally confronted with the challenge of combining measures of productivity, eco-friendly and ethical production, and economic efficiency into one analysis model and standardized indicators. This may lead to prioritizing and a narrow focus that contradicts the "cross-functional process-oriented nature of the supply chain" (14, p.50).

- Industries differ. Some differ in the asset-revenue relationship, whereas some might differ in the global-local scale of their supply chain (14, p.55). The difference in industries goes hand in hand with issues in a comparison of supply chains and a normative viewpoint on them. For example, for a long time, a main focus of SCAs was on supply chains of industrial production, while SCAs have only recently started to be conducted in agricultural production.

- An important distinction can be found between innovative and functional product supply chains. The former can be characterized by short product life-cycles and unstable demands but at the same time high profit margins and flexibility to react to changes in supply and demand. When analyzing innovative supply chains, one has to keep the market-orientation and -responsiveness in mind. The latter functional product supply chains comprise the exact opposite, and an SCA would have to consider their tendency to prioritize efficient "cost reductions of physical material flows and [...] value creating processes" (14, p.38). Consequently, there is a difference in suitable performance measures (4).

Normativity

- The interpretation of performance indicators, such as productivity, has to be linked to causal models of underlying processes, i.e. "when calculating productivity[,] a causal link between revenue and labour is assumed implicitly" (14, p.50). Causality itself however is always prone to normativity.

- Keeping a holistic view on the supply chain and its management is crucial because "overall supply chain costs are not necessarily minimized, if each partner operates at his optimum given the constraints imposed by supply chain partners" (14, p.39). When a SCA shows some potential areas for improvement for a product's supply chain, a firm might want to act on the findings. One has to keep in mind however, that each firm, each subchain and each process is interwoven and interdependent. Actions and decisions at one point of the supply chain therefore have huge impacts on following processes. There exist "attempts to match the performance metric of individual supply chain managers with those of the entire supply chain, in an attempt to minimize the total loss associated with conflicting goals" (1, p.291). This view is deeply normative, since it is not possible to consider every partner's interests. In case of global supply chains, where the majority of power and profit is often centered in Europe, and the majority of production is centered in other parts of the world, a euro-centristic view may be clouding the analysis. Issues of a colonialist history and even trends of neo-colonialism can be very problematic and the source of several biases.

- SCAs can be combined with other methodological approaches. These include a Meta-Analysis of multiple supply chains of a specific product, potentially over time, to gain insights into aspects such as the carbon footprint [2, 5, 8]. Life cycle assessment can be named as another important method in this field that attempts to analyze the (socio-)environmental impact of a product through its lifespan.

- A SCA can be a useful tool to investigate supply chains for ethical and environmental concerns.

- In terms of the environment, there is an increasing trend to improve supply chains, e.g. in terms of the length of product life cycles and recycling issues (1). SCAs can be used to "address problems in the food system" (5, p. 336) or to asses issues concerning aspects of sustainability, for example the carbon footprint or chemical pollution of the environment along the production and consumption of goods and services.

- Regarding human ethical issues, issues of transparency of unethical behavior can emerge along the supply chain. At each step, from the farmers to the workers in production, the retailers, suppliers and the customers, people interact with each other and ethical decisions are taking place. Customers can especially influence fair trade, transparency, and ethical development or a lack thereof among the supply chain with their consumption behavior (12). However, some aspects are focussed on more frequently, e.g. child labor, wages and ecological sustainability of production processes. Agreeing on what is "fair" often is a first challenge when tackling ethical issues along supply chains because the definition of fairness may differ among stakeholders (12). As an example for new developments on this aspect, the German government recently agreed on a new law that requires companies to assure the compliance of basic human rights along the supply chain. This can be seen as a first attempt to govern and influence global supply chains regarding the working conditions.

Outlook

There are several new approaches regarding SCAs. A uniting criterion is that all approaches combine SCAs with another method or disciplinary focus.

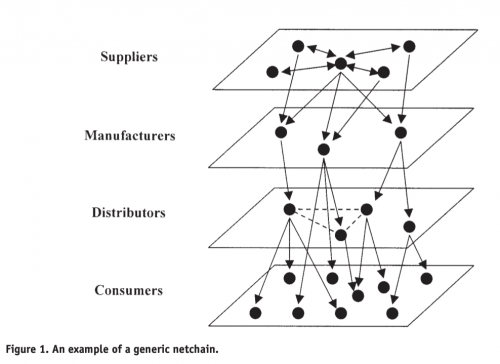

- SCAs can, for example, be interpreted into "netchain analysis" (6, p.7). Here, researchers go a step further than classical SCAs, taking into account all types of interdependencies (pooled, sequential & reciprocal). This is possible by combining a SCA with a network analysis.

- The Internet enables new forms of exchange, transaction, standardization, collaboration and also inter-organizational relationships.

- A field of sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) is also emerging and staring to not only optimize a supply chain in economic terms but in social and ecological terms, too (13). It has to be kept in mind, that global supply chains hereby differ greatly from local supply chains that function on a smaller scale.

Key Publications

Beamon, B. M. 1998. Supply chain design and analysis: Models and methods. International journal of production economics 55(3), 281-294.

Sürie, C. & Wagner, M. 2005. Supply chain analysis. In Supply chain management and advanced planning, 37-63. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

References

(1) Beamon, B. M. 1998. Supply chain design and analysis: Models and methods. International journal of production economics 55(3), 281-294.

(2) Darmawan, M. A., Putra, M. P. I. F., Wiguna, B. 2014. Value chain analysis for green productivity improvement in the natural rubber supply chain: a case study. Journal of Cleaner Production 85, 201-21

(3) Dass, M. & Fox, G. L. 2011. A holistic network model for supply chain analysis. International Journal of Production Economics 131(2), 587-594.

(4) Fisher, M. L. 1997. What is the right supply chain for your product? Harvard business review 75, 105-117.

(5) Hawkes, C. 2009. Identifying innovative interventions to promote healthy eating using consumption-oriented food supply chain analysis. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition 4(3-4), 336-356.

(6) Lazzarini, S. Chaddad, F. & Cook, M. 2001. Integrating supply chain and network analyses: the study of netchains. Journal on chain and network science 1(1), 7-22.

(7) Ntabe, E. N. LeBel, L. Munson, A. D. & Santa-Eulalia, L. A. 2015. A systematic literature review of the supply chain operations reference (SCOR) model application with special attention to environmental issues. International Journal of Production Economics 169, 310-332.

(8) Onat, N. C., & Kucukvar, M. 2020. Carbon footprint of construction industry: A global review and supply chain analysis. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 124, 109783.

(9) Poluha, R. G. 2007. Application of the SCOR model in supply chain management. Cambria Press.

(10) Radwan, A. & Aarabi, M. 2011. Modeling Supply Chain Management Information System Using ARIS Framework. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, January, 22-24.

(11) Sahamie, R. Stindt, D. & Nuss, C. 2013. Transdisciplinary research in sustainable operations–an application to closed‐loop supply chains. Business Strategy and the Environment 22(4), 245-268.

(12) Schlegelmilch, B. B. & Öberseder, M. 2007. Ethical issues in global supply chains. Symphonya. Emerging Issues in Management (2), 12-23.

(13) Song, W. Ming, X. & Liu, H. C. 2017. Identifying critical risk factors of sustainable supply chain management: A rough strength-relation analysis method. Journal of Cleaner Production 143, 100-115.

(14) Sürie, C. & Wagner, M. 2005. Supply chain analysis. In Supply chain management and advanced planning, 37-63. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

(15) Taylor, D. H. 2005. Value chain analysis: an approach to supply chain improvement in agri‐food chains. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management.

(16) Webb, G. S. Thomas, S. P. & Liao‐Troth, S. 2014. Teaching supply chain management complexities: A SCOR model based classroom simulation. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education 12(3), 181-198.

(17) Wolf, J. 2011. Sustainable supply chain management integration: a qualitative analysis of the German manufacturing industry. Journal of Business Ethics 102(2), 221-235.

(18) Ayyildiz, E. & Gumus, A. T. 2021. Interval-valued Pythagorean fuzzy AHP method-based supply chain performance evaluation by a new extension of SCOR model: SCOR 4.0. Complex & Intelligent Systems 7(1), 559-576.

The author of this entry is Linda von Heydebreck.