Narrative Research

Quantitative - Qualitative

Deductive - Inductive

Individual - System - Global

Past - Present - Future

In short: Narrative Research describes qualitative field research based on narrative formats which are analyzed and/or created during the research process.

Contents

Background

Storytelling has been a way for humankind to express, convey, form and make sense of their reality for thousands of years (Jovchelovitch & Bauer 2000; Webster & Mertova 2007). 'Storytelling' is defined as the distinct tonality, format and presentation in which a story is told. The term 'narrative' includes both: the story itself, with its dramaturgy, characters and plot, as well as the act of storytelling (Barrett & Stauffer 2009). However, the term 'narrative' has been used used predominantly as a synonym for 'story' in academia for decades (Barrett & Stauffer 2009).

Psychologist Jerome Bruner introduced the notion of 'narrative' as being one of two forms of distinct modes of thinking in 1984 - the other being the 'logico-scientific' mode (Barrett & Stauffer 2009). While the latter is "(...) more concerned with establishing universal truth conditions" (Barrett & Stauffer 2009, p.9), the 'narrative' mode represents the broad human experience of reality. This distinction led to further investigation on the idea that 'narratives' are a central form of human learning about - and sense-making of - the world. Scholars began to recognize the role of analyzing narratives in order to understand individual and societal experiences and the meanings that are attached to these. This led e.g. to the establishment of the field of narrative psychology.

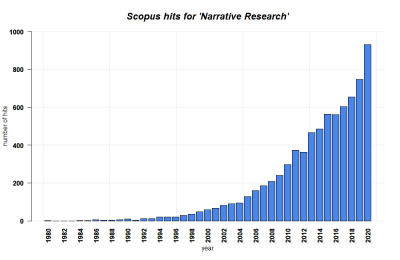

As a scientific method, Narrative Research - often just phrased 'narrative' - is a rather recent phenomenon (Barrett & Stauffer 2009; Clandinin 2006, see Squire et al. 2014). Narratives have developed towards modes of scientific inquiry in various disciplines in Social Sciences, including the arts, anthropology, cultural studies, psychology, sociology, and educational science (Barrett & Stauffer 2009). This development paralleled an increasing role of qualitative research during the second half of the 20th Century, and built on the understanding of 'narrative' as both a form of story and a form of meaning-making of the human experience. Today, Narrative Research may be used across a wide range of disciplines and is an increasingly applied form in educational research (Moen 2006, Stauffer & Barrett 2009, Webster & Mertova 2007).

What the method does

First, there is a distinction to be made: 'Narrative' can refer to a form of Science Communication, in which research findings are presented in a story format (as opposed to classical representation of data) but not extended through new insights. 'Narrative' can also be understood as a form of scientific inquiry, generating new knowledge during its application. This entry will focus on the latter understanding.

Next, it should be noted that Narrative Research entails different approaches, some of which are very similar to other forms of qualitative field research. In this Wiki entry, the distinctiveness of Narrative Research shall be accounted for, whereas the connectedness to other methods is mentioned where due.

Narrative Research - or 'Narrative Inquiry' - is shaped by and focussing on a conceptual understanding of 'narratives' (Barrett & Stauffer 2009, p.15). Here, 'narratives' are seen as a format of communication that people apply to make sense of their life experiences. "Communities, social groups, and subcultures tell stories with words and meanings that are specific to their experience and way of life. The lexicon of a social group constitutes its perspective on the world, and it is assumed that narrations preserve particular perspectives in a more genuine form" (Jovchelovitch & Bauer 2000, p.2). Narratives are therefore not merely forms of representing a chain of events, but a way of making sense of what is happening. Through the telling of a story, people link events in meaning. The elements that are conveyed in the story, and the way these are conveyed, indicates how the story-teller - and/or their social surrounding - sees the world. They are a form of putting reality into cultural and individual perspective. Also, narratives are never final but change over time as new events arise and perspectives develop (Jovchelovitch & Bauer 2000, Webster & Mertova 2007, Squire et al. 2014, Moen 2006).

Narrative Research is "(...) the study of stories" (Polkinghorne 2007, p.471) and thus "(...) the study of how human beings experience the world, and narrative researchers collect these stories and write narratives of experience." (Moen 2006, p.56). The distinctive feature of this approach - compared to other methods of qualitative research with individuals, such as Interviews or Ethnography - is the focus on narrative elements and their meaning. Researchers may focus on the 'narratology', i.e. the structure and grammar of a story; the 'narrative content', i.e. the themes and meanings conveyed through the story; and/or the 'narrative context', which revolves around the effects of the story (Squire et al. 2014).

One common approach in Narrative Research is the usage of narratives in form of spoken or written text or other types of media as the data material for analysis. This understanding is comparable to Content Analysis or Hermeneutics. A second understanding focuses on the creation of narratives as part of the methodological design, so that the narrative material is not pre-developed but emerges from the inquiry itself (Squire et al. 2014, Jovchelovitch & Bauer 2000). In both approaches, 'narrative' is the underlying "frame of reference" (Moen 2006, p.57) for the research. An example for the latter understanding is the 'Narrative Interview'.

Narrative Interviews

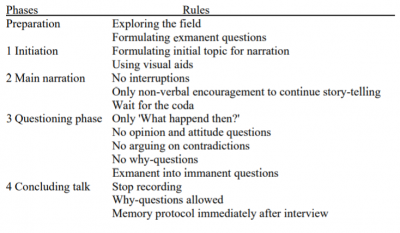

The Narrative Interview is an Interview format that "(...) encourages and stimulates an interviewee (...) to tell a story about some significant event in their life and social context." (Jovchelovitch & Bauer 2000, p.3). 'Narrative Interviewing' "is considered a form of unstructured, in-depth interview with specific features." (Jovchelovitch & Bauer 2000, p.4) To this end, it is a form of the Open Interview, which - compared to Semi-structured and Structured Interviews - is relatively free from deductively pre-developed question schemata: "To elicit a less imposed and therefore more 'valid' rendering of the informant's perspective, the influence of the interviewer should be minimal (...) The [Narrative Interview] goes further than any other interview method in avoiding pre-structuring the interview. (...) It uses a specific type of everyday communication, namely story-telling and listening, to reach this objective." (Jovchelovitch & Bauer 2000, p.4) Here, it is central that the interviewer appreciate the interviewee's perspective, by using the subject's language and by posing "as someone who knows nothing or very little about the story being told, and who has no particular interests related to it" (ibid, p.5). The interview is then transcribed and analyzed using different forms of coding (see Content Analysis), with a focus on the narrative elements. For more information on the methodological foundations of conducting and analyzing narrative Interviews, please refer to Jovchelovitch & Bauer 2000.

Narrative Inquiry as collaborative story-creation

In a third understanding of Narrative Research, which is most commonly referred to as 'Narrative Inquiry', 'narratives' are more than the underlying phenomenon - they are a central methodological element. 'This approach dissolves the barrier between researcher and subject further, and the collaboration between both is central to the methodological design (Clandinin 2006, Moen 2006). This type of narrative research does not apply an 'outsider's perspective', but instead is "(...) collaboration between researcher and participants, over time, in a place or series of places, and in social interaction with milieus. An inquirer enters this matrix in the midst and progresses in the same spirit, concluding the inquiry still in the midst of living and telling, reliving and retelling, the stories of the experiences that made up people's lives, both individual and social." (Clandinin 2006, p.20, citing Clandinin & Connelly 2000). To this end, Clandinin (2006) distinguishes between the re-telling of stories that Interview participants tell the researchers, and the telling of stories that the researchers experience themselves, e.g. in ethnographic studies. The difference is not so much of methodological nature as it is in the purpose and perspective of the research (Barrett & Stauffer 2009). In this understanding, 'Narrative Inquiry' is a reflexive and iterative process, with the researchers entering into a field of experiences, telling their own stories, telling the stories of other participants, and dialogically co-creating joined stories with them (Moen 2006). The created narratives serve as a way of presenting the research experiences, but also as forms of data for the analysis of the joint and conveyed experiences.

In terms of practical methodology, this form of narrative inquiry is very closely related to methods of Ethnography, which are based on the active participation in the field, i.e. the social situation of interest, and the creation of qualitative data in form of field notes. The distinctive component of Narrative Inquiry is the focus on narratives. Clandinin (2006, p.47f) explains the methodological approach as following: "As we enter into narrative inquiry relationships, we (...) negotiate relationships, research purposes, transitions, as well as how we are going to be useful in those relationships. These negotiations occur moment by moment, within each encounter, sometimes in ways that we are not awake to" or "in intentional, wide awake ways as we work with our participants throughout the inquiry. As we live in the field with our participants, whether the field is a classroom, a hospital room or a meeting place where stories are told, we begin to compose (...) a range of kinds of field texts from photographs, field notes, and conversation transcripts to Interview transcripts. As narrative inquirers work with participants we need to be open to the myriad of imaginative possibilities for composing field texts. (...) As we continue to negotiate our relationships with participants, at some points, we do leave the field to begin to compose research texts. This leaving of the field and a return to the field may occur and reoccur as there is a fluidity and recursiveness as inquirers compose research texts, negotiate them with participants, compose further field texts and recompose research texts." Data may be gathered in form of "field notes; journal records; interview transcripts; one's own and other's observations; storytelling; letter writing; autobiographical writing; documents (...); and pictures" (Moen 2006, p.61) and analyzed by forms of Content Analysis.

Strengths & Challenges

- Narratives have their own inherent structure, formed by the narrating individual. Therefore, while narrative inquiry itself provides the benefits and challenges of a very open, reflexive and iterative research format, it is not non-structured, but gains structure by itself (see Jovchelovitch & Bauer 2000)

- Webster & Mertova (2007, p.4) highlight that research methods that understand narratives as a mere format of data presented by the subject, which can then be analyzed just like other forms of content, neglect an important feature of narratives: Narrative Research "(...) requires going beyond the use of narrative as rhetorical structure, to an analytic examination of the underlying insights and assumptions that the story illustrates". Further, "Narrative inquiry attempts to capture the 'whole story', whereas other methods tend to communicate understandings of studied subjects or phenomena at certain points, but frequently omit the important 'intervening' stages" (ibid, p.3), with the latter being the context and cultural surrounding that is better understood when taking the whole narrative into account (see Moen 2006, p.59).

- The insights gained through narratives are subjective to the narrator, which implies advantages and challenges. Compared to an 'objective' description of, e.g. a chain of events, the narration provides insights about the individual's interpretation and experience of the events, which may be inaccessible elsewhere, and shine light on complex social phenomena: "Narrative is not an objective reconstruction of life - it is a rendition of how life is perceived." (Webster & Mertova 2007, p.3; see Moen 2006, p.62). However, this subjective representation of events or a situation may be distorted and differ from the 'real' world. Squire et al. (2014) refer to this distinction as different forms of 'truth' that researchers may be interested in: either representations of the physical world or of social realities which present the world through the lense of the narrator. Jovchelovitch & Bauer (2000, p.6) suggest that the researchers take both elements into consideration, first fully engaging with the subjective narrative, then comparing it to further information on the physical 'truth'. They should try "(...) to render the narrative with utmost fidelity (in the first moment) and to organize additional information from different sources, to collate secondary material and to review literature or documentation about the event being investigated. Before we enter the field we need to be equipped with adequate materials to allow us to understand and make sense of the stories we gather." Moen (2006, p.63), by comparison, explains that "(...) there is no static and everlasting truth", anyway.

- This conflict between different 'truths' also has consequences for the quality criteria for Narrative Inquiry, especially for those research endeavors that create narratives themselves. To this end, 'usefulness' and 'persuasiveness' of the created narratives have been suggested as quality criteria (Barrett & Stauffer 2009) or, as Webster & Mertova (2007, p.4) put it: "Narrative research (...) does not strive to produce any conclusions of certainty, but aims for its findings to be 'well grounded' and 'supportable' (...) Narrative research does not claim to represent the exact 'truth', but rather aims for 'verisimilitude'". (For more thoughts on validity in Narrative Inquiry, see Polkinghorne (2007)). For the analysis of narratives, a 'trustworthy' set of field notes and Interview data may serve as a measure of quality, which the researchers created through prolonged engagement in the field, triangulation of different data sources and the active search for disconfirmation of one's research results (see Moen 2006, p.64). Also, researchers "(...) need to cogently argue that theirs is a viable interpretation grounded in the assembled texts" (Polkinghorne 2007, p.484).

- Further challenges may arise during the active collaboration of the researcher in the field. For example, "(...) the researcher and the research subjects interpret specific events in different ways or (...) the research subjects question the interpretive authority of the researcher" (Moen 2006, p.62). Further comparable issues of qualitative field research are noted in the entry on Ethnography.

Normativity

- As mentioned before, Narrative Inquiry methodology is in many regards similar to methods in Ethnography, and shares elements with Hermeneutics, Qualitative Content Analysis, and Open Interviews. Generally, it can be seen as a purely qualitative and inductive approach that focuses on limited temporal and spatial scales.

- "(...) [A] distinguishing feature of Narrative Research is a "(...) move away from an objective conception of the researcher-researched relationship" (...) to one in which the researcher is deeply involved in the research relationship. (...) In this process, narrative inquiry, becomes to varying degrees a study of self, or self alongside others, as well as of the inquiry participants and their experience of the world." (Barrett & Stauffer 2009, p.11f, quote from Pinnegar & Daynes 2007, p.11). The autobiography of the researcher, as well as personal beliefs and practices and ethical positionality is brought into the research endeavor, which should be acknowledged in the process and results. "Narrative inquirers cannot bracket themselves out of the inquiry but rather need to find ways to inquire into participants’ experiences, their own experiences as well as the co-constructed experiences developed through the relational inquiry process." (Clandinin 2006, p.47)

- Within this interaction in the field, the researcher must be aware of the consequences of creating new narratives in the studied subjects and situations, which is why Clandinin (2006, p.53) mentions "(...) the importance of thinking in responsive and responsible ways about how narrative inquiry can shift the experiences of those with whom we engage". In addition, Moen (2006, p.62) mentions that the narratives written down as a result of the research inquiry are themselves subject to interpretation: "The story has been liberated from its origin and can enter into new interpretive frames, where it might assume meanings not intended by the persons involved in the original event. (...) [T]he narrative that is fixed in a text is thus considered an “open work” where the meaning is addressed to those who read and hear about it. Looking on narrative as an open text makes it possible to engage in a wide range of interpretations".

Outlook

Barrett & Stauffer (2009, p.16) claim that "[n]arrative inquiry is still in its early stages of development (...). It will be subject to contestation over the years as the methodology develops, and other pathways are marked out." This can be substantiated by the dispersed literature with its diverse understandings (see References), and the rather recent development of the discourse around narratives.

Key Publications

Veroff et al. 1993. NEWLYWEDS TELL THEIR STORIES: A NARRATIVE METHOD FOR ASSESSING MARITAL EXPERIENCES. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 10. 437-457.

- An example study that applied Narrative Interviews.

References

(1) Stauffer, S.L. Barrett, M.S. 2009. Narrative Inquiry: From Story to Method. In: Barrett, M.S. Stauffer, S.L. (eds). 2009. Narrative Inquiry in Music Education. Troubling Certainty. Springer VS. 7-17.

(2) Clandinin, D.J. 2006. Narrative Inquiry: A Methodology for Studying Lived Experience. Research Studies in Music Education 27. 44-54.

(3) Jovchelovitch, S. Bauer, M.W. 2000. Narrative interviewing [online]. LSE Research Online.

(4) Webster, L. Mertova, P. 2007. Using Narrative Inquiry as a Research Method. An introduction to using critical event narrative analysis in research on learning and teaching. Routledge London, New York.

(5) Squire, C., Davis, M., Esin, C., Andrews, M., Harrison, B., Hyden, L-C, and Hyden, M. 2014. What is narrative research? London: Bloomsbury

(6) Moen, T. 2006. Reflections on the Narrative Research Approach. International Journal of Quantitative Methods 5(4). 56-69.

(7) Polkinghorne, D.E. 2007. Validity Issues in Narrative Research. Qualitative Inquiry 13(4). 471-486.

The author of this entry is Christopher Franz.