Citizen Science

| Method categorization | ||

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Qualitative | |

| Inductive | Deductive | |

| Individual | System | Global |

| Past | Present | Future |

In short: Citizen Science is the conduct of research by members of the general public, usually in collaboration with, or under the direction of, professional researchers.

Background

The concept Citizen Science publicly gained prominence by two different approaches. The most prominent approach in environmental science to this day goes back to the US ornithologist Rick Bonney from Cornell University who, starting in the late 1990s, framed Citizen Science as a form of public participation in scientific activity, especially in the form of data gathering done by amateurs (1, 2). This understanding is rooted in the 1960s when Cornell researchers already included volunteers in ornithological research (1, 5). Even before, one could argue that the difference between scientists and amateurs was blurry, as naturalists - for instance in the Victorian age - were often not trained scientists yet a vital source of data (8).

A second famous approach is based on the work of UK sociologist Alan Irwin who, in 1995 (see Key Publications), framed Citizen Science as "developing concepts of scientific citizenship which foregrounds the necessity of opening up science and science policy processes to the public" (Riesch & Potter 2014, p.1), focusing on the role of citizens as stakeholders in informed decision-making processes.

Partly due to these different backgrounds of the concept, “[t]he meaning of "citizen science” is in fact not very clear, particularly when formulated on a science policy level, where it is often defined too broadly without making the distinctions that scientists work with” (Kullenberg & Kasperowski 2016, p.2). Terms such as 'participatory science', 'civic science' or 'community-based monitoring' may also be understood as a form of Citizen Science (1).

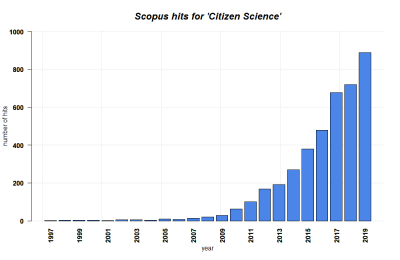

Today, Citizen Science is frequently used in biology, conservation and ecology (topics include e.g. birds, insects or water quality), followed by geographic information research and epidemiology (1, 2, 6, 8). It has also found other fields, including Astronomy, Agriculture, Arts and Education (see for example this agricultural study and this participatory approach in Astronomy.) Its presence in scientific publications has increased significantly since the early 2000s, which may be attributed to an increased usage of digital platforms for citizen engagement (1).

What the method does

Annotation: While the following explanation of Citizen Science focuses on Rick Bonney's approach of amateurs gathering data, the differences between the two predominant understandings will be addressed below.

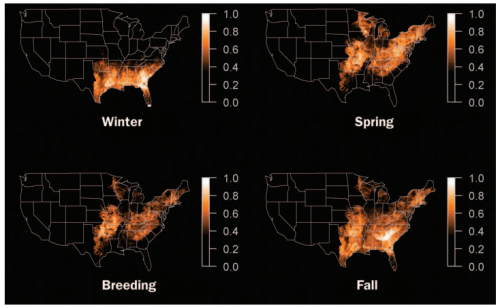

In the sense of Bonney, Citizen Science describes a form of data gathering that is done by amateur enthusiasts in the field, in cities or gardens. Observations are noted in data forms based on instructions in pre-determined protocols stating the how, when and where of data gathering (4). The data are transmitted online to the researchers and can often be accessed in form of visualisations (e.g. maps) by the contributors afterwards. The intended outcome of a Citizen Science project can range from increasing general data availability and scientific outreach to solving specific local problems or promoting public interest and knowledge on a certain topic. (7)

Citizen Science's unique characteristic is that it enables researchers to sample data across different scales - from regional up to global spatial scales - as well as repeated measurements spanning several years. This allows a scaling of data based on contribution of many participants, allowing a broader and more holistic perspective that would be not possible solemnly on the workload of the researchers. Bird-watching may take place in gardens of a smaller area for one season while the method can likewise integrate geographic information upscaled to a global scale over several years. Often, the collected data is numeric, e.g. number of birds counted, and at which date. This allows to accumulate larger observations about bird migration.

Differences between Irwin and Bonney

- In his 1995 book, Alan Irwin states that "Citizen Science tries to find a way through the usual monolithic representations of ‘science’ and the ‘public" (Irwin 1995, p.ix). To him, "such matters as policy are not merely 'applications' of academic analysis nor are they simply 'implementations' - instead the whole question of how interventions are made is a major issue in itself." (Irwin 1995, p.xi). His conceptualization addresses how public needs and knowledge can be implemented into scientific processes in order to open up the barriers between the two sub-systems. To him, Citizen Science means "a form of science developed and enacted by citizens themselves" (Irwin 1995, p.xi).

- Rick Bonney, on the other hand, describes Citizen Science as a method that "enlists the public in collecting large quantities of data across an array of habitats and locations over long spans of time" (Bonney et al. 2009, p.977). This understanding has a stronger methodological perspective on the approach as opposed to Irwin whose definition also refers to science policy.

- Overall, Citizen Science may be seen both as a form of data gathering conducted by amateurs but also concerns the analysis of data and, even more so, its interpretation and application in direct contact with public actors. Wiggins & Crowston (2011) summarize this diversity within the concept by defining Citizen Science as "a form of research collaboration involving members of the public in scientific research projects to address real-world problems." (Wiggins & Crowston 2011, p.1). This combines the diverging perspectives and allows for a broader understanding of the concept's essentials. In a way, the emergence of transdisciplinary research may be seen as a concession to Irwin: while Citizen Science is today predominantly applied in Bonney's way, Irwin's idea of involving public actors into scientific processes is highly relevant - simply in a different methodological area.

Strengths & Challenges

- Citizen Science allows for access to data that would otherwise be inaccessible (covering long periods of time and wide spatial arrays) (6, 8).

- There is an educational quality to Citizen Science: participants not only learn about the respective subjects but also about scientific work (see Normativity).

- The research questions addressed through Citizen Science (in form of amateur data gathering) must take into consideration that most contributors will not be able to assess complex data. Instead, simple counting or observations can be expected (4). "Projects demanding high skill levels from participants can be successfully developed, but they require significant participant training and support materials such as training videos" (Bonney et al. 2009, p.979).

- In the case of bird watching (but also similar data types), errors may result from participants confusing bird species. This must be addressed through additional information material for the amateur scientists. (4)

- Citizen science always demands some sort of supra-infrastructure or project, since the data cannot be analysed by the participating citizens

Normativity

Complexity of the method and the analysed data

- The research questions addressed through Citizen Science (in form of amateur data gathering) must take into consideration that most contributors will not be able to assess complex data. Instead, simple counting or observations can be expected. "Projects demanding high skill levels from participants can be successfully developed, but they require significant participant training and support materials such as training videos" (Bonney et al. 2009, p.979).

Everything normative related to this method

- A strong bias may be imposed on the data due to divergent understandings of the data gathering procedure in the respective amateur individuals, diminishing the objectivity, reliability & validity of the process. This (alleged) lack of quality in the data gathered by amateurs has led to dispute over the validity of the method for scientific investigation and publication, which is to date an ongoing debate (6). A sample error can be minimized, for instance through additional information material, training and understandable, precise protocols for data collection (4, 6, 8).

- While researchers gain data through Citizen Science, the involved citizens get involved in scientific processes, strengthening their scientific literacy and learning about the subjects their are participating in (4, 7). This can also lead to positive social impacts, enabling communities to address local issues in a scientific manner and providing agency or even empowerment‚ to the respective actors (6).

- Citizen Science is a method of transdisciplinary research since it includes public actors into research processes. This element induces some normative notions that are addressed in the wiki entry on transdisciplinarity.

Outlook

Open questions for the method

- The diversity of terms and lack of precise definition should be overcome in the future to improve the application of Citizen Science (6, 7).

- The same is stated with regards to the redundancy in Citizen Science projects. Instead of designing new projects from the ground, functioning projects should be applied to new areas of interest (6).

Possible future developments - thoughts about the future of the method

- "Citizen Science (...) has over the past decade become a very influential and widely discussed concept with many scientists and commentators seeing it as the future of genuine interactive and inclusive science engagement (...)" (Riesch & Potter 2014, p.107). As new areas of academia develop participatory research designs, the potential of these approaches are becoming more and more visible (8). Therefore, after years of development and despite a lack of definite conceptualization, Citizen Science should be taken seriously and supported from more areas within academia (8).

- The spreading of Citizen Science approaches to local communities may support the incorporation of traditional knowledge into science policy and improve the science-society relationship in the future (6).

- The growing global availability of internet access improves amateurs' access to Citizen Science projects and increases the potential availability of data for researchers (7).

Key Publications

Theoretical

Irwin, A. 1995. Citizen Science: A Study of People, Expertise and Sustainable Development. London: Routledge.

- Debates the role of the public in science and vice versa, focusing on matters of risk and sustainable development.

Kullenberg, C. Kasperowski, D. 2016. What is Citizen Science? - A Scientometric Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 11(1)

- Examines the different conceptualizations and uses of Citizen Science in close to 2000 articles.

Bonney, R. et al. 2009. Citizen Science: A Developing Tool for Expanding Science knowledge and Scientific Literacy. BioScience 59(11).

- Describes an explanatory model for developing a citizen science project.

Empirical

Evans, C., E. Abrams, R. Reitsma, K. Roux, L. Salmonsen, and P. P. Marra. 2005. The neighborhood nestwatch program: participant outcomes of a citizen-science ecological research project. Conservation Biology 19:589–594

- Focuses on the scientific literacy outcomes of the citizens involved in a Citizen Science project.

References

(1) Kullenberg, C. Kasperowski, D. 2016. What is Citizen Science? - A Scientometric Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 11(1)

(2) Riesch, H. Potter, C. 2014. Citizen science as seen by scientists: Methodological, epistemological and ethical dimensions. Public Understanding of Science 23 (1) : 107- 120

(3) Irwin, A. 1995. Citizen Science: A Study of People, Expertise and Sustainable Development. London: Routledge.

(4) Bonney, R. et al. 2009. Citizen Science: A Developing Tool for Expanding Science knowledge and Scientific Literacy. BioScience 59(11). 977-984.

(5) Cohn JP. 2008. Citizen science: Can volunteers do real research? BioScience 58 (3): 192–197.

(6) Bonney, R. et al. 2014. Next Steps for Citizen Science. SCIENCE 343, 1436-1437.

(7) Wiggins, A. Crowston, K. 2011. From Conservation to Crowdsourcing: A Typology of Citizen Science. 2011 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

(8) Dickinson, J.L. Zuckerberg, B. Bonter, D.N. 2010. Citizen Science as an Ecological Research Tool: Challenges and Benefits. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 41. 149-172.

Further Information

- For a list of interesting Citizen Science-Projects from around the world please read the Wikipedia entry on the method.

The author of this entry is Christopher Franz.