Ethnography

| Method categorization | ||

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Qualitative | |

| Inductive | Deductive | |

| Individual | System | Global |

| Past | Present | Future |

Annotation: Ethnography is both a process and an outcome - the final written product - of qualitative research (3). This article will focus on the process, giving an overview of different kinds of ethnographic research and its correlating methods.

Background

Ethnography can be regarded one of the most important qualitative research methods that looks back on a long tradition but also many transitions. The foundations of modern Ethnography reach back about a hundred years. Until 1900, ethnographic information mostly originated from the collection of anthropological artifacts and descriptions of indigenous communities that were collected and reported by amateurs, e.g. missionaries or travellers, and subsequently evaluated by 'armchair' anthropologists. By the beginning of the 20th Century, then, anthropologists began to go into the field and get in contact with people themselves instead of relying on second-hand information (1).

An influential figure for the subsequent development of Ethnography was Bronislaw Malinowski, a Polish anthropologist who is considered to be the founder of fieldwork and participant observation methods relevant to Ethnography to this day (1, 8). He invested himself in 'classical' ethnographic work, spending months with a Melanesian community and gathering insights that he published in his 1922 work "Argonauts of the Western Pacific". He systematically recorded and later taught his approach to fieldwork, which heavily furthered the methodological foundations of anthropology (1).

The methodological approach to Ethnography was further influenced by the early 20th century work of the Chicago School of sociology, which is also responsible for major developments of interview methodology (see Open Interviews and Semi-structured Interviews). Sociologists in Chicago attempted to study individuals within the city by observing and interviewing them in their everyday lives, and furthered the methodological groundwork for the field this way (1).

Overall, Ethnography is historically and practically most closely related to the discipline of Anthropology and constitutes a defining method of this discipline (8). Still, the theoretical reflections and methodological approaches also apply to research endeavours in other Social Sciences. Today, Ethnographic research no longer focuses on investigating 'exotic' communities, but deals with a diverse range of topics, including media studies, health care, work, education, communication, gender, relations to nature, and others (7, 9).

What the method does

Ethnography is not strictly a method, but rather a "culture-studying culture" (Spradley (2), p.9). It is a scientific approach to how research should be conducted that includes a set of methods, but also a set of theoretical considerations on how to apply these methods (1). Ethnography attempts to understand the social world and actions of human beings in a specific cultural and societal surrounding of interest to the researcher (8). The researcher intends to systematically describe this culture and understand another way of life from the 'native point of view' (Spradley (2), p.3). "Rather than studying people, ethnography means learning from people." (Spradley, p.3). According to Malinowski, three aspects are of interest to the researcher: what people say they do (customs, traditions, institutions, structures); what they actually do; and typical ways of thinking and feeling associated with these elements (1). The latter may be expressed directly by the studied individuals, but may also be *tacit knowledge,* i.e. **knowledge that is inherent to the culture but taken for granted and communicated only indirectly through word and action (Spradley (2), p.5). Ethnographic research attempts to infer this knowledge by listening carefully, observing and studying the culture in detail (2, see below).

The term *culture* "(...) refers to *the acquired knowledge that people use to interpret experience and generate social behavior."* (Spradley (2), p.5). In this regard, not only 'exotic' enclosed societies such as the indigenous community studied by Malinowski are of interest in ethnographic research, but also small-scale cultures such as a classroom, a family or a restaurant (3).

Observations are often supplemented by qualitative ethnographic interviews to gain a deeper understanding into previously observed situations. These are a form of open interview that focus on how the interviewees classify and describe their experiences and positions concerning their social context. Interviews may take place in-between observations, or in dedicated, set-up interview situations, and also with groups of interviewees (1). The Interviewees may be asked about broad or specific situations. Elements that may be learned about are: people involved, places used, individual acts, groups of acts that combine into activities or routines, events, objects, goals, time and feelings (4). The ethnographic interview differs from standard open interviews in that it tries not to impose any pre-conceived notions and structures on how the interviewee might view, define or classify these elements according to his/her worldview. Instead, the questions are formulated so that the interview is almost entirely guided by the interviewee's responses (1, 5). This way, the researcher may be able to extract insight into "(...) contextual understandings, shared assumptions and common knowledge upon which a respondent's answers are based (...). Ethnographic questions are used to elicit the perceptions and knowledge that guide behavior, while discouraging individuals from translating this information into a form corresponding to the researcher's revealed understanding and language." (Johnston et al. 1995, p.57f). In such an interview, the power relation between researcher and interviewee is shifted, because the researcher does not have much that he/she wants to learn about, but the interviewee has all the information to offer that is of interest to the researcher. Therefore, a trustful relationship between the researcher and the interviewee is of special importance (4, see Normativity).

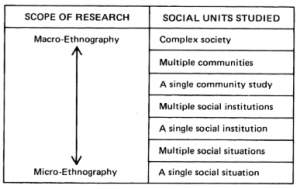

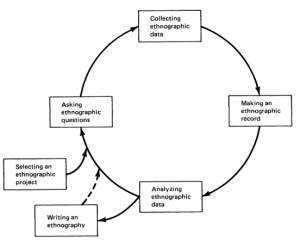

Ethnography is thus a very open and inductive process, with the researcher acting like an explorer who does not rely on strictly pre-defined questions leading his/her research, but rather goes into the field openly and develops new questions as the first results emerge from the data collected after some time (1, 3, 8). In this reflexive practice, the research design continuously evolves during the study. The research is done in a circular process, which sets ethnographic research apart from classical theory-led, linear social science approaches (3, see Figure below). The scope of the research is decreased with every circulation: In terms of the research questions, the researcher first asks rather general *descriptive* questions about the situation at hand. The data is analyzed and based on the results, the focus is narrowed down: next, *structural* questions are asked, before *contrast* questions are used in the next step to further reduce the scope of the research design. The same applies to the data collection: Initially, the observations are rather descriptive, but become more and more focused and selective as the ethnographic research continues (3)

The data gathered in Ethnography may be quantitative (e.g. statistical summaries of specific actions), but are primarily qualitative, e.g. photographies, audio files, maps, descriptions of phenomena, structures and ideas, or even objects (1, 9). Overall, therefore, ethnographic methodology may be defined as qualitative and inductive, focusing on the present individual while allowing for inferences on the past and the whole societal system that is observed.

Strenghts & Challenges

The focus of Ethnography on gathering data in the 'natural' context is crucial for the quality of the results. Being in the very situation and watching what people do and learning about their thoughts on the situation as it happens allows for more insightful conclusions. The alternative - having individuals report in a dedicated, external setting, before or after the situation happening - might be biased since people do not always do what they say they do (1). For further challenges, see Normativity.

Normativity

- Early ethnographic work focused on the understanding and exploration of 'exotic' communities, 'hidden' somewhere in a different part of the world, as part of colonial interventions. Today, Ethnography has shifted, and any cultural or societal setting may be analyzed using ethnographic methods. Even seemingly mundane situations in cultural contexts more familiar to the researcher may reveal 'strange' and 'exotic' elements when analyzed thoroughly (1, 8). This realisation emphasizes that 'reality' is not the same to all people. While this idea of *naive realism* is a tempting assumption, it should be set aside for ethnographic research which attempts to learn about what different elements of life - words, but also concepts - mean to people in different social and cultural settings (2). As Spradley puts it: "Ethnography starts with a conscious attitude of almost complete ignorance." (Spradley, p.4) This new perspective on life is generally interesting as it scrutinizes *what is normal and what is not.* - Ethnography can be seen as a powerful tool to inform people about other people's lifeworlds, connect societies and broaden perspectives (see (2)). It may therefore be helpful for sustainable development which relies on the acceptance and incorporation of diverse perspectives and (sometimes conflicting) demands. - O'Reilly (1) discusses implications of ethical field work. For ethical reasons, the researcher should not disguise his/her presence but be open about his/her role and research intent. Consent should be gained by all individuals that are studied and disclosure on the subsequent usage of the data as well as confidentiality should be provided. At the same time, being too open and transparent might complicate the immersion of the researcher in the studied situation, thus negatively affect the data gathered, or even be impossible due to the iterative nature of the research process. The researcher should attempt to balance openness so that no harm is done, but not constantly remind everyone of his/her role as a researcher in order to ensure useful research results. For further elaborations on ethical considerations, refer to O'Reilly (1).

Quality criteria - Malinowski emphasized that the observations done in the field should not be conducted randomly, but systematically. They should not only focus on the extraordinary elements of each situation, but rather provide a comprehensive collection of all individual elements. This also involves the detailed, written description of the context and setting as well as the methods of the observation (1). - Time is a crucial factor for observation since it takes some time for the researcher, being an outsider to the analyzed context, to get acquainted with the situation and gain a feeling of the people's perspective (8). This also reduces the risk of the people behaving differently than they usually would due to the researcher's presence, since they get used to his/her presence after some time. Additionally, spending a sufficient amount of time with the situation of interest allows for the researcher to change the directions of the research and narrow down the research focus after first conclusions emerge (see *What the method does*) (1). - Participation is an important element of ethnographic fieldwork. Instead of relying only on external observations, the researcher should join the observed people and get in contact with the respective situations to get a better feel for an insider's perspectives. However, this participation might influence the 'objectivity' of the observation (1).

Outlook

The book "Digital Environments' (6) reflects upon the future development of digital anthropology in the face of the increasing role of 'digital environments' as a sphere for social interaction, which raises new methodological challenges for researchers investigating communities in this field.

Key Publications

Malinowski, B. 1922. Argonauts of the Western Pacific. An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. Routledge London, New York. Available at [1](http://www.bohol.ph/books/Argonauts/Argonauts.html) (last accessed on 15.07.2020)

O'Reilly, K. 2005. Ethnographic Methods. Routledge Oxon.

An extensive description of how Ethnography is applied.

Brewer, John D. 2001. Ethnography. Understanding Social Research. Open University Press.

A compact overview on Ethnography.

References

(1) O'Reilly, K. 2005. Ethnographic Methods. Routledge Oxon.

(2) Spradley, J.P. 2016. The Ethnographic Interview. Waveland Press.

(3) Spradley, J.P. 2016. Participant Observation. Waveland Press.

(4) Westby, C. Burda, A. Mehta, Z. 2003. Asking the Right Questions in the Right Ways. Strategies for Ethnographic Interviewing. The ASHA Leader 8(8). 4-17.

(5) Johnston, R.J. Weaver, T.F. Smith, L.A. Swallow, S.K. 1995. Contingent Valuation Focus Groups: Insights From Ethnographic Interview Techniques. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review 24. 56-69.

(6) Frömming, U.U. Köhn, S. Fox, S. Terry, M. (eds). 2017. Digital Environments. Ethnographic Perspectives Across Global Online and Offline Spaces. transcript Verlag, Bielefeld.

(7) Brewer, J.D. 2003. The future of ethnography. Qualitative Social Work 1. 245-249.

(8) Mader, E. et al. Einführung und Präpodeutikum Kultur- und Sozialanthropologie. Available at [2](https://www.univie.ac.at/sowi-online/esowi/cp/einfpropaedksa/einfpropaedksa-1.html) (last accessed on 21.07.2020)

(9) Atkinson, Paul/Delamont, Sara/Coffey, Amanda (2007): Handbook of Ethnography. London et al.: Sage.

(10) Creswell, John (2013): Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. London et al.: Sage.