Difference between revisions of "Sampling for Interviews"

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

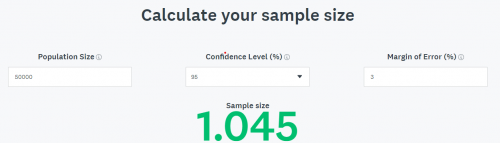

[[File:Sample Size Calculator - Surveymonkey.png|500px|thumb|right|'''Sample Size Calculator'''. Source: [https://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/sample-size-calculator/ SurveyMonkey]]] | [[File:Sample Size Calculator - Surveymonkey.png|500px|thumb|right|'''Sample Size Calculator'''. Source: [https://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/sample-size-calculator/ SurveyMonkey]]] | ||

| − | Taking this multitude of factors into account, sample size calculators on the Internet, such | + | Taking this multitude of factors into account, sample size calculators on the Internet, such as this one(https://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/sample-size-calculator/), can help to get an idea of which sample size might be suitable for your study. Keep in mind that when determining the sample size, the estimated response rate needs to be accounted for as well, so you most likely need to invite more people for the survey than the calculated sample size indicates. For more on sampling sizes in Surveys, please refer to Gideon (2012) who dedicates a chapter on finding the right sample size. |

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 11:31, 1 August 2024

In short: This entry provides tips on how to sample participants for different forms of Interviewing Methodology. It includes tips and deliberations on defining the target population, choosing the right sample size and applying different forms of sampling strategies. For more on Interviews, please refer to the Interviews overview page.

Contents

The general rationale of sampling

A sample is a selection of individuals from a larger population that researchers investigate instead of investigating the whole population, which is not possible for a range of reasons. Sampling is a crucial step in research: "[o]ther than selecting a research topic and appropriate research design, no other research task is more fundamental to creating credible research than obtaining an adequate sample." (Marshall et al. 2013, p.11). This is also true for Interview methdology: the creation of a good sample directly affects the validity of the research results (7). How many people you ask your questions, hand out your questionnaire to, or invite to your Focus Groups directly influences the broadth and depth of the created insights. Inviting too few people might not deliver sufficient material to answer your research questions. An overly large sample, then again, might be superfluous, i.e. increase the costs and organisational effort of your project without providing further insights. A sample of the study population that is not representative of the full breadth of possible viewpoints and experiences within the whole population will definitely influence your results, and non-representative samples can happen no matter the sample size, but are less of a problem for bigger samples than for small ones. Thus, approaching the question of sampling can generally be guided by Ockham's Razor - you need a sample that is as big as necessary, but as small as possible. However, this is often easier to say than to apply.

As a rule of thumb, the more open an interviewing approach is, the smaller the sample is going to - and needs to - be. The more structured the methodology, the bigger the required sample. This is because of the depth of the created data in qualitative approaches, which needs time to be qualitatively assessed. Quantitative surveys, by comparison, rely on responses that can be analyzed by means of statistical approaches. These do not only deal better with large samples than, say, qualitative content analysis approaches, but even require larger numbers for valid insights. Still, this general dichotomy does not directly guide an individual interview approach. So first, let us have a look at the seletion of a study population, before examining what the literature suggests for the topic of sample sizes. Last, we will have a look at different forms of sampling (7).

Defining the study population

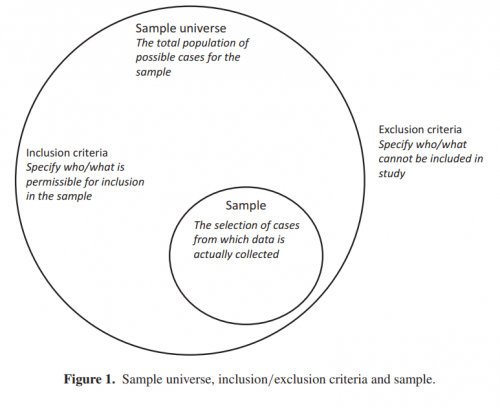

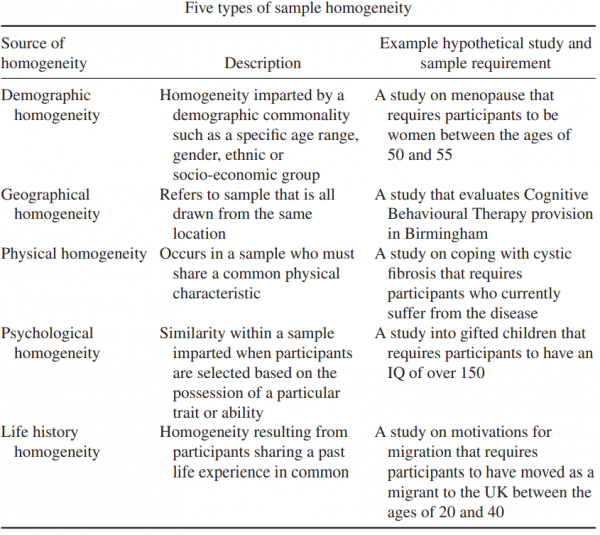

In a first step, the 'sample universe' - also known as 'study population' or 'target population' - needs to be defined. To do so, the researcher develops inclusion and / or exclusion criteria to guide the selection of all individuals that are theoretically of interest to answer the research question (see Figure). The inclusion and exclusion criteria that are applied will determine the characteristics of the sample universe. This universe can thus become very homogeneous as well as very heterogeneous (see Table). These criteria are mostly guided by theory, in accordance to the research purpose, questions, and methodological design, and potentially with regards to other work that has been done before. Further, organisational elements already play a role here, like geographical access, or the level of access that the researcher has to the population. Within this population, the sample will be drawn, which will help answer the research questions.

The sampling universe can be designed to be rather homogenous, or heterogenous. As you can see in the table below, a homogenous sample may be of interest to enable research on more specific phenomena. As an example, a researcher might be interested in how individuals with a specific position in an organisational context perceive a distinct topic. Therefore, they will conduct expert interviews with such individuals, and accordingly define the sampling universe more homogenously and strict (Meuser & Nagel 1991, p.442f). By comparison, "[t]he rationale for gaining a heterogeneous sample is that any commonality found across a diverse group of cases is more likely to be a widely generalisable phenomenon than a commonality found in a homogenous group of cases. Therefore, heterogeneity of sample helps provide evidence that findings are not solely the preserve a particular group, time or place, which can help establish whether a theory developed within one particular context applies to other contexts" (Robinson 2014, p.27).

The definition of the sampling universe further differs for qualitative and quantitative approaches. For qualitative interviews, the general idea is to select interviewees in a way that promises "information-rich" interviews (1). The inclusion and exclusion criteria should be selected accordingly, and focus on individuals that will likely provide deeper and highly relevant insights into the topic of interest. For quantitative approaches, the inclusion and exclusion criteria may be less strict. While medical surveys may be interested in anyone with a specific disease, more general sociological research might simply include everyone working at a specific company, or every individual of a certain age in a selected city, or every potential voter in a country. So overall, the exclusion and inclusion criteria that define the sampling universe depend mostly on the intended methodological approach, as well as the research questions.

Choosing the right sample size

Before drawing the sample from the whole population within the sampling universe, the next step is to clarify the amount of individuals that are planned to be interviewed. This differs between Interview formats.

Qualitative Interviews

Qualitative Interviews rely on questions and answers that help the researcher thoroughly understand the interviewee's perspective on the respective topic in order to conclusively investigate the research questions. It is not the researcher's primary interest to be able to count the number of times a specific thing was said, and to make a tally for the according code in the analysis. Indeed, quantitative analysis approaches do exist also for qualitative data (see Content Analysis). Generally however, qualitative interviews will be assessed qualitatively, and focus on investigating and understanding what interviewees have said in order to get a broad and deep overview of all relevant aspects - opinions, experiences - that the interviewees have on the topic of interest. Instead of a large number of cases, the complexity and diligence of the interview conduction are relevant to the quality of the results (Baker & Edwards 2012, p.39). To this end, semi-structured interviews allow for larger sample sizes than open interviews, since their analysis is more structured based on the pre-determined interview guide.

In general, the most important concept for the determination of the right sample size in research is 'saturation'. However, while saturation is an often-used concept, it is ill-defined (1; 2; 3). Commonly, researchers justify their sample size by stating they have reached saturation, but rarely explain what this means. Historically, and methodologically, ('theoretical') saturation emerged from [Grounded Theory] research and refers to iterative, qualitative research which after some times reaches the point when further increasing the size of the sample will not provide any more insights that could further amend the theory that has been developed so far (Malterud et al. 2016, p. 1758). This means that the people you have asked so far have told you everything of relevance which the whole population that you could possible ask will be able to tell you. When you have reached saturation in your results, your sample - your N has been big enough (2). It is time to wrap up the Interview results; they likely cover all relevant facets. The expected point of saturation guides the planned sample size before starting the study, while conducting it, and when discussing the validity of the results (2).

Saturation as a guiding principle also relates to the quality of the selected interviewees (1). You can find more information on sampling strategies in the paragraph below. For now, however, we will focus on the conflict that emerges from the fundamental idea of saturation: you can only know if you have reached a saturation in your data by analyzing the data as you get it, so that you could stop conducting interviews as soon as the results altogether lack new insights (Baker & Edwards 2012, p. 18). However, analyzing the data in-between interviewing more individuals is a logistical challenge, since analysis takes time and should not be done in passing. Also, researchers typically need to state their sample size before starting the research and not update it mid-gathering (1; 3;7). Interviewing costs money and requires resources, which need to be granted and organized beforehand and can rarely be flexibly adjusted as necessary. Further, this iterative approach can also influence your interviews. When you know how you will code the gathered qualitative interview data, and maybe even have some results already, this might consciously or unconsciously guide the way you conduct further interviews: you'd bias yourself. By comparison, a strict separation of data gathering and data analysis might reveal a lack of saturation only long after the interviewing phase, or show that you have conducted way more interviews than needed.

So, while saturation is often used and generally required, there is no easy guide to determining it. There is no general accepted N that would suffice for every qualitative interview study (3). Marshall et al. (2013) propose three approaches to determining adequate sample sizes: first, using recommendations from other researchers, which, as they show, range from 6-10 interviews for phenomenological studies, to 20-50 for Grounded Theory studies. However, as the authors highlight, these recommended numbers are rarely explained by those other researchers. Second, adopting the sample size from comparable studies, which, again, may be quite arbitrary. Third, by statistically assessing one's own study in terms of its thematic saturation. However, very few to none of the studies they reviewed actually employed these three strategies, but instead "(...) made superficial references to data saturation or altogether omitted justification for sample size." (Marshall et al. 2013, p. 20). Eventually, the authors conclude that as a rough guideline, Grounded Theory qualitative studies should use 20-30 interviews, single case studies 15-30 interviews. They also call for researchers to consider the expectations of the respective journal.

Hennink et al. (2017) follow the idea of statistically investigating saturation, doing so in their own line of interviews. Here, they differentiate between *code* saturation - which are new topics emerging in the interview responses - and *meaning* saturation - which are new insights into the respective codes that provide a better understanding. They find code saturation to happen at around 9 qualitative interviews, which is similar to the findings in comparable studies, but also highlight that meaning saturation for all codes may take more interviews, or may even never be reached for all codes at all. Their findings thus '(...) underscore the need to collect more data beyond the point of identifying codes and to ask not whether you have "heard it all" but whether you "understand it all" - only then could saturation be claimed.' (Hennink et al. 2017, p.605).

What is important to keep in mind is that the number of interviewees is just one part of the equation. You can interview as many individuals as you like, but if they are not at all representative of the diversity of the whole sampling universe, you will still not reach saturation with this approach. Therefore, the selection of individuals (see sampling strategies below) to be representative of the whole sampling universe will strongly influence how large your sample needs to be in order to reach saturation.

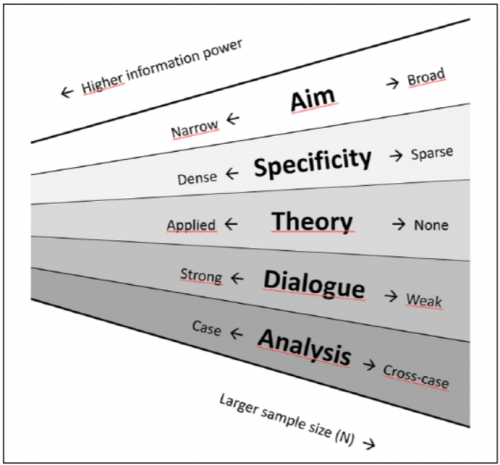

Malterud et al. (2016, p.1754) underscore that "(...) sample size cannot be predicted by formulare or by perceived redundancy." Instead, they claim five quality criteria of the gathered data - which make up its "information power" - to be relevant to determine the adequate sample size. These are the aim of the study, the specificity of the sample, the extent to which theory guides the interviewing process, the quality of the dialogue data, as well as the focus of the analysis (see Figure). These criteria are presented as a frame in which researchers can iteratively assess their own research approach, and also assess other empirical studies in terms of their sample size. However, the authors underscore that their model "(...) is not intended as a checklist to calculate N but is meant as a recommendation of what to consider systematically about recruitment at different steps of the research process."

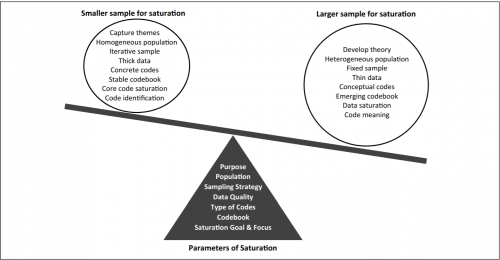

Hennink et al .(2017), too, provide a set of criteria. In combination, these shall help reflect upon, although not necessarily entirely determine, the required sample size before data gathering. These criteria include the purpose of the study, the study population, the sampling strategy, the quality of the data, the type of codes and the quality of the codebook, as well as the intended level and type of saturation (see Figure). Overall, they advise researchers to more actively reflect upon, and more transparently communicate, their own process of reaching saturation when conducting qualitative interviews, and to spend time beforehand to consider the sample size needed for their specific study: "Using these parameters of saturation to guide sample size estimates *a priori* for a specific study and to demonstrate within publications the grounds on which saturation was assessed or achieved will likely result in more appropriate sample sizes that reflect the purpose of a study and the goals of qualitative research." (Hennink et al. 2017, p.607) For more insights, please refer to Hennink et al. (2017 p. 606f).

Overall, it becomes obvious that there is no simple answer to "How many people do you need to ask?" for qualitative Interviews. The aforementioned insights and criteria may guide the process, and orientating oneself on previous research certainly helps. However, the question of the 'right' sample size remains unsolved and is matter of ongoing discussions, which every researcher could contribute to by critically reflecting upon one's own sampling strategy.

Focus Groups

Focus Groups are not comparable to Interviews in every aspect, but also require a sample that is both informative and thematically exhaustive, without burdening the research team with too much organisational effort. Generally, many of the elements that can guide qualitative interview sampling may therefore also apply to Focus Groups. More specifically, however, Focus Groups strongly focus on group-internal interactions and dynamics. Tang & Davis (1995, p.474) highlight that the ideal group size for Focus Groups "(...) maximizes output of information and minimizes group dissatisfaction. It is believed that valid and rich information can be generated as a result of participants' willingess to express without inhibition." Because of this, the size of the group influences the data that the researcher can gather in the first place. Tang & Davis (1995) generally recommend between four and twelve members in a Focus Group, but express that bigger groups may inhibit maximized information output by every participant, and may lead to competitive or inconsiderate group dynamics. However, smaller groups might be too passive and constrained, and were found to generate fewer ideas than bigger groups. They also highlight that the nature of the study, the complexity of the topic, as well as the diversity, ability, expectations and needs of the group members play critical roles in determining the best group size. Also, organisational factors such as the format and length of the session, and the number or duration of questions play a role. Overall, they claim the biggest influencing factor to be the aim of the study: more explorational studies may need smaller groups, while bigger groups are more suited to structured approaches.

In addition to the size of each focus group, the overall number of focus groups is of relevance. Based on an literature review, Carlsen & Glenton (2011) highlight that the majority of studies held less than 10 focus groups in total. However, the authors indicate a severe lack of reflection on this number. Of their reviewed 220 studies, 183 did not justify the number of focus groups they held. Those who did referred to practical reasons or to recommendations by the available literature. Most (28 of 37) claimed to have reached saturation, half of which did not 'convincingly' describe the process which led to this assessment (Carlsen & Glenton 2011, p.5). Their results suggest that more methodological work on Focus Groups is needed to increase rigor in the determination of the adequate number of Focus Groups, which may well also be the case for the size of each group.

Survey Research and quantitative interviews

Quantitative Interview approaches, i.e. surveys based on questionnaires or structured interviews, intend to represent the target population adequately, and provide a sufficiently large sample for quantitative analyses. The sample chosen for the survey should make generalizations and statistical inferences about that population possible. Here, broader samples are more relevant than choosing individuals that promise deep insights, since surveys do not focus as much on understanding reasoning and perspectives in depth as much as qualitative interviews.

When determining the sample for surveys, **a bigger sample size is almost always better**. A bigger size will reduce skewness of the sample, and even out statistical errors that would influence the quantitative analysis. However, surveys also cannot cover the complete target population. You cannot sample endlessly, as organisational and financial restrictions limit the possible amount of survey respondents: you cannot hand out surveys to bypassers on the street for years, and you will never reach everyone in your target population via the Internet. Importantly, a sample that is very big may always lead to some kinds of analysis results if you search long enough. This is called statistical fishing, which is a common challenge in quantitative analyses. Therefore, the sample should not be drawn all over the place but should relate to the study objective.

Also, the adequate sample size for a survey depends on the study objective, the sampling universe and the sampling method. Importantly and contrary to popular belief, the mere size of the target population is of little or no relevance unless the target population is relatively small, i.e. only consists of a few thousand people. The composition of the sampling universe (target population) is of bigger importance. In case of simple random sampling, for example, the heterogeneity of the target population plays a role. Here, also the confidence interval you aim for, and how you want to analyze your data (e.g. analysis by subgroups, type of statistical analysis) are highly relevant to determine the adequate sample size.

Taking this multitude of factors into account, sample size calculators on the Internet, such as this one(https://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/sample-size-calculator/), can help to get an idea of which sample size might be suitable for your study. Keep in mind that when determining the sample size, the estimated response rate needs to be accounted for as well, so you most likely need to invite more people for the survey than the calculated sample size indicates. For more on sampling sizes in Surveys, please refer to Gideon (2012) who dedicates a chapter on finding the right sample size.

Sampling strategies

After the sample universe is defined, you can approach the third element in accordance with the sample size: the sampling strategy. This refers to the way that the researcher draws the (previously) defined number of individuals from the whole sampling universe. As shown before, the sampling approach strongly influences the sample size, and is itself strongly influenced by the research intent, sampling universe, and research methdology. There are various sampling strategies, the most important of which will be presented below (based on Robinson 2014).

Random & convenience sampling

Random sampling is a typical approach in surveys. In this approach, individuals are drawn randomly: for example, they are randomly approached with the survey or questionnaire on the street, by randomly calling telephone numbers from a list, or via e-mail newsletters online. This approach can still be systematic, e.g. by choosing individuals in a specific interval from a list. It can also take the form of cluster sampling, where specific groups within the overall population - e.g. a few schools out of all schools in a district - are randomly chosen to represent to the whole population of students (8). For surveys, this random approach is common: since the sample size can be much bigger here, the step of boiling down the study population to the actual sample is less sensitive to specific criteria. Validity in this approach emerges from numbers, so differences between sampled individuals do not matter as much (8). However, overly small samples, especially for broadly defined study populations, may make non-significant results hard to interpret. Were they not significant because there is no significant effect, or was the sample too small? Random sampling is also imaginable for qualitative research, but since the sample sizes are mostly small here, there is a big risk of omitting important perspectives.

By comparison, convenience sampling refers to asking people which are easy to access, for example people that you come across in a shopping mall. Be aware of the difference to random sampling: convenience sampling can potentially be as representative of the whole study population as any form of random sampling - or, stochastically speaking, even more so. Yet, most commonly, convenience sampling imposes a selection bias since it favors a specific group of people. In the shopping mall in the afternoon, you'll mostly meet people who are not currently working, who like to go to the Shopping Mall. Another example is the fact that psychology studies have famously often been conducted with psychology students, who are easy to access for researchers, but hardly representative of the whole country, and do not really represent a random sample, for that matter (7). Convenience sampling is also imaginable for qualitative research, but the sampling bias imposed by this strategy weighs even heavier here. For both qualitative and quantitative approaches, generalisations are hard to draw from convenience sampling-based research. If you still plan to go for convenience sampling, the gap between the sampling universe and the actual sample should not be too wide. For example, if the sample universe is defined as "young university adults with interest in psychology", then conveniently sampling psychology students will be less of an issue than if your sampling universe was "every citizen below the age of 30" (7).

Snowball sampling

Basically, snowball sampling is a form of random or convenience sampling. In snowball sampling, the researcher initially selects few individuals to interview. After the interview, the interviewee is asked to recommend further people that might be relevant to the research. This way, the researcher widens the sample with every step. Unfortunately, this approach may strengthen biases that existed with the initial interviewee selection, and another bias can be imposed by the recommendation rationale of each interviewee. Snowball sampling is possible for quantitative research, but mostly done for qualitative approaches where a specific group of individuals is of interest.

Purposive sampling

Purposive sampling is directed strongly by theoretical pre-assumptions. The researchers assume that a specific kind of individual will represent an interesting perspective on the research topic, and is therefore included in the sample. This is most common in qualitative research, and includes a range of variations:

Stratified sampling

In stratified sampling, several groups are created, which are defined by shared characteristics of the individuals which are then assigned to these groups. For example, you create groups with people from different educational backgrounds, with different diseases, or different age groups. The categories may also overlap, like in a Venn Diagram ("cell sampling"). Then, a fixed number of individuals are randomly drawn from each of these groups. This approach intends to provide a representative composition of different perspectives, preconditions and experiences.

Quota sampling

Quota sampling works like stratified sampling, but instead of fixed numbers of individuals per category, there are minimum numbers of individuals, which can be exceeded. This way, the relevant groups are covered, but the researcher is more flexible in gathering individuals.

Case Study sampling

For single case studies, various approaches are imaginable: the researcher might be interested in extreme or deviant cases, or individuals which promise to be very information-rich, or plainly very typical representations of a specific phenomenon. These are identified and sampled.

Concluding remarks

To summarize, there are four major parts to sampling:

1) defining the sampling universe with exclusion and inclusion criteria in accordance with the intended methodology and the research question,

2) defining the sample size in accordance with a demand for saturation (qualitative approaches), statistical significance (quantitative approaches), and representativeness regarding the research question,

3) choosing the sampling strategy in accordance with the same criteria, and all the while

4) documenting your sampling approach, so that your research is reproducible, and other researchers understand how you worked.

Sampling is a complex issue of Interview methodology which is not easily solved. As with many elements of scientific methodology, sampling requires experience, and there is room for learning from failed attempts. Further, we encourage the exchange on sampling approaches and critical reflections upon one's own - and others' - sampling strategies. This way, the validity of scientific claims will be improved, and the different demands of qualitative and quantitative research, as well as different forms of Interviews, will be more adequately fulfilled. If you want to read more about the normativity of Sampling, please refer to the entry on Bias in Interviews.

References

(1) Hennink, M.M. Kaiser, B.N. Marconi, V.C. 2017. Code Saturation Versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Qualitative Health Research 27(4). 591-608.

(2) Malterud, K. Siersma, V.D. Guassora, A.D. 2016. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qualitative Health Research 26(13). 1753-1760.

(3) Marshall, B. Cardon, P. Poddar, A. Fontenot, R. 2013. DOES SAMPLE SIZE MATTER IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH?: A REVIEW OF QUALITATIVE INTERVIEWS IN IS RESEARCH. Journal of Computer Information Systems

(4) Tang, K.C. Davis, A. 1995. Critical factors in the determination of focus group size. Family Practice 12(4). 474-475.

(5) Carlsen, B. Glenton, C. 2011. What about N? A methodological study of sample-size reporting in focus group studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology 11(26).

(6) Baker, S.E., Edwards, R. 2012. How many qualitative interviews is enough? Expert voices and early career reflections on sampling and cases in qualitative research. National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper.

(7) Robinson, O.C. 2014. Sampling in Interview-Based Qualitative Research: A Theoretical and Practical Guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology 11(1). 25-41.

(8) Fife-Schaw, C. 2000. Surveys and Sampling Issues. Research methods in psychology 2. 88-104.

(9) Gideon, L. 2012. Handbook of survey methodology for the social sciences. Springer.

The author of this entry is Christopher Franz.