Why statistics matters

(The author of this entry is Henrik von Wehrden.)

Contents

Statistics as a part of science

Science creates knowledge. This knowledge production follows certain principles. Being a statistician with all the experience I had the privilege to perceive to date, I recognize this as one of the biggest challenge of statistics. Many people, especially those new to statistics, feel a strong urge towards freedom. I think this is wonderful. Radical thinking moves us all forward. However, because of this urge for freedom already existing knowledge is often not valued, as the radical thought for the new is stronger than the appreciation of the already established. This is, in my experience, the first grave challenge statistics face. People reject the principles of statistics out of the urge to be radical. I say, be radical, but also stand on the shoulders of giants.

The second grave challenge of statistics is numbers per se. Most people are not fond of numbers. Some are even afraid. Fear is the worst advisor. Numbers are nothing to be afraid of, and likewise, statistics are nothing to be afraid of either. Yet learning statistics is no short task, and this is the third obstacle I see.

Learning a scientific method, any scientific method, takes time. It is like learning an instrument or learning martial arts. Learning a method is not just about a mere internalisation of knowledge, but also about gaining experience. Be patient. Take the time to build this experience. Within this Wiki, I give you a basic introduction of how statistics can help you to create knowledge, and how you can build this experience best.

Occam's razor

"Entities should not be multiplied without necessity."

The Franciscan friar William of Occam almost single-handedly came up with one of the most fundamental principles to date in science. He basically concluded, that "everything should be as simple as possible, but as complex as necessary." Being a principle, it is suggested that this thought extends to all. While in his time it was rooted in philosophy or more specifically in logic, Occam's razor turned out to propel many scientific fields later on, such as physics, mathematics, biology, theology, mathematics and many more. It is remarkably how this principle purely rooted in theoretical consideration generated the foundation for the scientific method, which would surface centuries later out of it. It also poses one of the main building blocks of modern statistics as William of Occam came up with the principle of parsimony. While this is well known in science today, we are up until today busy discussing whether things are simple or complex. Much of the scientific debate up until is basically a pendulum swing between these two extremes, with some people oversimplifying things, while others basically say that everything is so complex we may never understand it. Occam's razor concludes that the truth is in between.

Examples:

How to make a Curry.

I love Curry. I, who had the privilege to work in Nepal for sixth months, had the opportunity to enjoy some good curry. How does one make a good curry? I think this is an ideal case of Occam's razor. You need quite some ingredients, Chillies, Ginger, Garlic, Onions, some vegetables of your choice, coconut milk, etc. Do you need hundreds of things? Probably not. An ideal curry contains as many ingredients as one needs, but not more.

You have been Sherlocked

Many people are familiar with the fantastic Sherlock Holmes. His creator, Sir Arthur Canon Doyle was obviously a great admirer of Occam's razor. Hence, it surfaces a lot in Sherlock but can be also found in lots of other characters from fiction (Contact, Dr. House, Star Trek).

Occam Programming language

Occam's razor is also used in computer programming. Programmers need to use a very simple combination of letters or words to create an executable command in a program. In 1983 David May created the programming language Occam to keep the process of programming as simple as possible.

The scientific method

The scientific method was a true revolution since it enabled science to test hypotheses through observation. Before, science was vastly dominated by theorizing -that is developing theories- yet testing theories proved to be more difficult. While people or scientists tended to observe since the dawn of humans, making such observations in a systematic way opened a new world in science. Especially Francis Bacon influenced this major shift, for which he layed the philosophical foundation in his "Novum Organon".

All observations are normative, as they are made by people. This means that observations are constructs, where people tend to see things through a specific "lens". A good example of such a specific normative perspective is the number zero, which was kind of around for a long time, but only recognised as such in India and Arabia in the 8th-9th century (0). Today, the 0 seems almost as if it was always there, but in the antique world, there was no certainty whether the 0 is an actual number or not. This illustrates how normative perspectives change and evolve, although not everybody may be aware of such radical developments as Arabic numbers.

A very short history of statistics

Building on Occam's razor and the scientific method, a new mode of science emerged. Rigorous observation and the testing of hypotheses became one important building block of our civilisation. One important foundation of statistics was probabilistic theory, which kind of hit it off during the period known as Enlightenment.

Probability was important as it allowed to differentiate between things happening by chance, or following underlying principles that can be calculated by probability. Of course, probability does not imply that it can be understood why something is not happening by chance, but it is a starting point to get out of a world that is not well understood. Statistics, or more importantly probability, was however not only an important scholar development during the enlightenment, but they also became a necessity. On of the first users of probability was Jan de Wit, leader in the Netherlands from 1652 to 1672. He applied the probabilistic theory to determine proper rates of selling annuities. Annuities are payments which are made yearly but back in the days states often collected them during times of war. He stated that annuities and also life ensurances should be conected to probability calculations and mortality records in order to determine the perfect charge of payment.

Following the Peace of Westphalia, nations were formed at a previously unknown extent, effectively ending the European religious wars. Why is that relevant, you wonder? States need governance, and governance builds at least partly on numbers. Statistics enabled states to get information on demographics and economic development. Double bookkeeping contributed as well. Numbers became a central instrument of control of sovereigns over their nations. People started showing graphs and bar charts to show off their development, something we have not quite recovered from ever since. For example in 1662 John Graunt estimated the population of London by using records on the number of funerals per year, the death rate and the average family size and came to the conclusion that London should have about 384 000 citizens. Statisticians were increasingly in demand to account for data, find relations between observations, and basically to find meaning in an increasing plethora of information. The setup and calculation of experiments created another milestone between the two world wars, effectively propelling modern agriculture, psychology, clinical trials and many other branches of science.

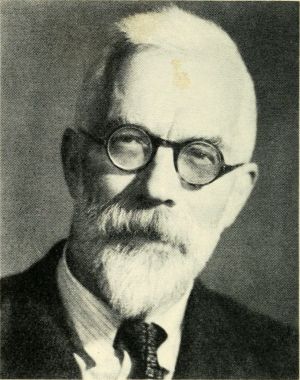

Hence, statistics became a launchpad for much of the exponential development we observe up until today. While correlation and the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) are a bit like the daily bread and butter of statistics, the research focus of the inventor of the ANOVA -Ronald Fisher- on Eugenics is a testimony that statistics can also be misused or used to basically create morally questionable or repugnant assumptions. Despite these drawbacks, statistics co-evolved with the rise of computers and became a standard approach in the quantitative branch of science.

With computers, long-standing theories such as Bayes Theorem could be tested, and many new statistical methods got developed. Development of statistics led also to new developments in science, as for instance, multivariate statistics paved the road to look at messy datasets, and machine learning revolutionised the way we approach information in the age of computers.

For another perspective on the history of statistics, we can highly recommend you the Radiolab Podcast about Stochsticity.

Key concepts of statistics

Models as simplifications

Statistics is about simplification of complex realities, or about finding patterns in more or fewer complex data. Such simplifications are often called models.

According to the statistician Box "..all models are wrong, but some models are useful. However, the approximate nature of the model must always be borne in mind." This famous quotation (Box and Draper 1987, page 424) is often misunderstood. Box talked about specific -in this case polynomial- models. These represent approximations or simplifications and are hence inertly all wrong. Still, some of these specific models can be useful. With this, Box highlights the previously known principle of parsimony.

The quote is, however, often used to reject the idea of models altogether, which is simply a mistake. There is another famous quote that is associated with Winston Churchill "I only believe in statistics that I doctored myself". Most likely this sentence was never said by Churchill but was associated with him by Goebbels to discredit him. This showcases that the discussion about the approximation of truth through statistics is a controversial one. Never forget that statistics can generate approximations of truths, but I would argue it cannot generate fundamental truths.

Is that a problem? NO! In most cases, approximations will do. In other words, it is quite easy to prove something as a fact, but it is much harder to prove that something is not a fact. This is what any good conspiracy theory is built upon. Try to prove that flying saucers do not exist. Yet if one would land in front of you, it is quite evident that there are flying saucers.

This debate about truths has preoccupied philosophy for quite some time now, and we will not bother ourselves with it here. If you look for generalisable truths, I advise going to philosophy. But if you look for more tangible knowledge, you are in the right place. Statistics is one powerful method to approximate truths.

Samples

If we would want to understand everything through statistics, we would need to sample everything. Clearly, this is not possible. Therefore, statisticians work with samples. Samples allow us to just look at a part of a whole, hence allowing to find patterns that may represent a whole.

Take an example of leave size in a forest that consists of Beech trees. You clearly do not need to measure the leaves of all trees. However, your sample should be representative. So, you would want to sample maybe small trees and large trees, trees at the edge of the forest, but also in the center. This is why in statistics people tend to take a random sample.

This is quite important, since otherwise, your analysis may be flawed. Much in statistics is dealing with sample designs that enable representative samples, and there are also many analytics approaches that try to identify whether samples are flawed, and what could be done if this is the case. Proper sampling is central in statistics. Therefore, it is advisable to think early within a study about your sample design.

Analysis

Analysing data takes experience. While computers and modern software triggered a revolution, much can go wrong. There is no need to worry, as this can be avoided through hard work. You have to practise to get good at statistical analysis. The most important statistical test can be learned in a few weeks, but it takes time to build experience, enabling you to know when to use which test, and also how to sample data to enable which analysis.

Also, statistical analysis is made in specific software tools such as R, SPSS or Stata, or even programming languages such as Python or C++. Learning to apply these software tools and languages takes time. If you are versatile in statistical analysis, you are rewarded, since many people will need your expertise. There is more data than experienced statistical analysts in the world. But more importantly, there are more open questions than answers in the world, and some of these answers can be generated by statistical analysis.

Presenting statistical results

Generalisations on statistics

The map is not the territory Basically means that maps are generalisation which therefore details from the rich details of the territory. It took me very long to get this sentence. While it simply suggests that reality is different from the representation in map, I think the sentence puzzled me because in my head it is kind of the other way around. The territory is not the map. This is how a statistician would probably approach this matter. Statistics are about generalisation, and so are maps. If you would have a map that would contain every detail of the reality how you perceive it, it would not only be a gigantic map, but it would be completely useless for orientation in the territory. Maps are so fantastic at least to me because they allow us through clever and sometimes not so clever representation of the necessary details to orientate ourselves in unknown terrain. Important landmarks such as mountains and forests rivers or buildings allow us to locate ourselves within the territory. Many maps often coined thematic maps include specific information that is represented in the map and that follows again a generalisation. An example are land-use maps which may contain information about agriculture pastures forests and urbanisation, but for sake of being understandable do not differentiate into finer categories. Of course for the individual farmer this would not be enough in order to allow for nuanced and contextual land use strategy. However, through the overview we gain an information that we would not get if the map would be too detailed. Statistics work kind of in the same way. If we would look at any given data point within a huge dataset we would probably incapable of understanding general patterns. Likewise do statistics draw conclusion from the complicated if not complex data and are able to find meaning or explanations in the plateau of data. Hence I agree that if I want to get a feeling about a specific city that I visit then a map would probably not bring me very far in terms of absorbing the atmosphere of the city. Yet without a map it would be tricky to know where I would be going and how I find my way home again. Our individual data points are often very important to -you guessed it- individuals but the overall patterns are important to many of us. Or at least they should be, I think. But this is another matter. The map is not the territory, but the territory is also not the map.

Bibliography

History of statistics by Wikipedia

External links

Videos

Bayes Theorem Here you can watch one of the most popular examples of probabilistic theory

Ronald Fisher The video is about the life and work of one of the most famous statisticians

Different sampling methods This video explains the most common sampling methods

Articles

More about the Quote "Standing on the shoulders of giants": Wikipedia, BBC

William of Occam: Life and Work by Wikipedia

How Occam's Razor Works: A comprehensive but well understandable treatise

What is the scientific method?: Step by Step

The "Baconian Method": A very brief overview

Francis Bacon and the Scientific Revolution: A historic perspective (brief)

0: Alarming news

History of our numerical system by Wikipedia

The Enlightenment by Wikipedia

Who was John Graunt?: A short biography

Han Solo and Bayes Theorem: An enjoyable explanation

One of the first clinical trials: The work by the statistician Austin Bradford Hill

Smoking cigarettes causes cancer and heart disease: A short paper

I only believe in statistics that I doctored myself: Being deceptive with statistics

All models are wrong. Some models are useful: A warning.

What is truth?: An insight into philosophy

Sampling: An explanation of different methods, types & errors