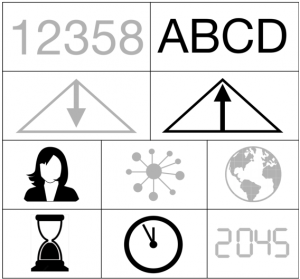

Gioia-Methodology

Quantitative - Qualitative

Deductive - Inductive

Individual - System - Global

Past - Present - Future

In short: In this article, we introduce the so-called Gioia-Methodology for the inductive and interpretivist analysis of qualitative data. This method is inspired by the methodology of Grounded Theory developed by Glaser and Strauss.

Contents

Background

The Gioia-Methodology is named after Dennis Gioia. In the 1990s, Gioia began collaborating with various management scholars to explain diverse management problems using Grounded Theory. At that time, the application of Grounded Theory was largely confined to researchers who, aligned with interpretivism, sought to challenge the dominant positivist or quantitative paradigm. Grounded Theory studies were distinctly different from what quantitative researchers considered scientific. Consequently, Gioia and his co-authors often received similar feedback from review panels of management journals: “The article is well-written and the theoretical contribution is promising, but how do we know that your findings are truly based on your interview data and not just made up?”

In response, Gioia developed his own approach to Grounded Theory, now known as the Gioia-Methodology. This method represents a systematic approach to inductive concept development and balances the often conflicting goals of developing new concepts inductively while meeting the high standards of rigor demanded by top journals. The Gioia-Methodolgy first appeared in print in Gioia and Chittipeddi (1991), followed by two other studies elaborating on the methodology used in the original work: Gioia, Thomas, Clark, and Chittipeddi (1994) and Gioia and Thomas (1996). In 2013, Gioia and colleagues published an article that comprehensively explained the approach from start to finish.

Gioia et al. emphasize in their article that their approach is closer to a methodology rather than a concrete method, even though it is often referred to as such. This means that deviations from the process are both possible and encouraged. However, according to Gioia and colleagues, it is crucial to provide a detailed description of the exact process of your analysis in the methodology chapter of your work. While deviations are acceptable, the defining characteristic of the Gioia Method remains its structured and systematic approach.

What the method does

The Gioia-Methodology is well-suited for inductive, qualitative-interpretive research and is based on two core assumptions. First, it assumes that reality within organizations is socially constructed. Second, it adopts an interpretive approach, meaning that the subject of research should be studied in a way that reflects the participants’ processes and understandings, while avoiding the imposition of external meanings by the researchers. According to Gioia and colleagues, participants are seen as “knowledgeable agents”—individuals who not only understand what they are doing, how they are doing it, and why, but who can also articulate these things in ways meaningful to them. All too often, researchers adopt theory-driven approaches, presuming to already know what is happening in a given setting. As a result, they may prematurely leap to an abstract level of analysis. In contrast, the Gioia-Methodology prioritizes giving voice to the informants during the early stages of data collection and analysis, creating rich opportunities to discover new concepts rather than merely affirming existing ones. Instead of having theory drive the data collection process, the Gioia-Methodology ensures that theoretical perspectives emerge grounded in the first-hand data. In alignment with Grounded Theory, the goal is to base the emergent theory on the participants’ understanding of their (constructed) world.

We will now describe the steps involved in the Gioia-Methodology. These steps are summarized in Figure 1 for clarity.

Since the Gioia-Methodology is primarily a method for data analysis, it is first necessary to establish a guiding research question and to generate or identify suitable data material. In most cases, the data consists of interviews or ethnographic studies to obtain both retrospective and real-time accounts from people experiencing the phenomenon of theoretical interest.

1st Order Analysis

The analysis begins with the creation of so-called “1st-Order Concepts”. This step is comparable to open coding in Grounded Theory. You summarize the data into concepts, using the language found in the data itself. In this way, the interpretations and experiences of the informants (and, for example, those of the ethnographer) are incorporated into the analysis. According to Gioia, 10 interviews can yield 50 to 100 1st-Order Concepts. These concepts don’t need to consist of a single word; they can also take the form of short sentences.

To capture the most significant concepts, it is essential not only to analyze the data individually but to also compare them across different sources. Gioia and colleagues therefore recommend a form of constant comparison, and triangulating data from different informants and time points to identify shared concepts. Developing comprehensive cross-reference lists can help track commonalities, relationships among major concepts, and emerging themes.

2nd Order Analysis

In the 2nd-Order Analysis, we transition firmly into the theoretical domain, where the researcher aims to develop an explanatory framework and place the story in a broader theoretical context. At this stage, the goal is to assess whether the concepts from the 1st-Order Analysis suggest themes that can describe and explain the observed phenomena.

By consulting the literature and identifying underlying explanatory dimensions, the research process moves from being purely inductive to incorporating elements of abductive reasoning. In this phase, data and existing theories are considered together. The 2nd-Order Analysis also aims to produce insights that are relevant beyond the immediate study.

Practically, this involves reviewing the 1st-Order Concepts and attempting to group them meaningfully. Patterns can be identified at this stage, allowing for the development of theoretical labels that group multiple 1st-Order Concepts. These abstract themes enable a shift away from the literal language of the data, facilitating the creation of unique themes. These themes can emerge either by developing a more general label that subsumes the 1st-Order Categories or by referencing the literature that accurately describes the emergent themes.

Once again, it is crucial to analyze the data across informants for significant patterns of convergence or divergence. A final iteration of constant comparison is conducted to determine whether there is enough evidence to support a theme as a reportable finding. Data collection ends when no new 2nd-Order themes are discovered (Theoretical Saturation).

2nd Order Aggregate Dimensions

After completing data collection and passing all data through the 1st and 2nd Order Analysis, the next step is to group the themes further. At this stage, approximately 25-30 2nd-Order Themes are summarized into about 3-5 aggregate analytical dimensions. These dimensions provide a superordinate framework for organizing the emerging findings. They should be as original as possible, describing the observed phenomenon in a way that no one else has done before.

Data Structure

Now comes the step that makes the Gioia-Methodology unique: creating a data structure from the 1st-Order Concepts, 2nd-Order Themes, and Aggregate Dimensions (see Figure 2). This is essentially a horizontal tree diagram that visually demonstrates how the aggregate dimensions emerged from the 2nd-Order Themes, and how those, in turn, were built from the 1st-Order Concepts. This diagram can be included as a figure in the Results Chapter. The data structure not only serves as a meaningful visual aid but also provides a graphic representation of the progression from raw data to terms and themes in the analysis—a crucial component for demonstrating rigor in qualitative research.

Grounded Theory Model

The final step is the development of a Grounded Theory Model, which includes not only all the major emergent concepts, themes, and dimensions but also their dynamic interrelationships. The Grounded Theory Model should illustrate the relationships among the emergent concepts that describe or explain the phenomenon of interest. The process of constructing the model involves assembling the boxes while placing particular emphasis on the arrows (see Figure 3).

Strengths & Challenges

The Gioia-Methodology incorporates the perspective of the informants through the 1st-order analysis and the theoretical, scientific perspective through the 2nd-order analysis in its systematic approach to inductive concept development. This not only allows for a qualitatively rigorous demonstration of the links between the data and the induction of new concepts but also provides inclusive, participant-based insights.

Normativity

The Gioia-Methodology addresses some of the challenges and critiques associated with Grounded Theory, particularly by providing a systematic structure that establishes a clear connection between empirical data and theoretical concept development. The key differences compared to classical Grounded Theory by Glaser & Strauss are:

- Transparent and Traceable Data Structure: The Gioia-Methodology develops a visual data structure model that illustrates how 1st-Order Concepts (terms used by informants) evolve into 2nd-Order Themes (theoretical concepts) and eventually into aggregate dimensions (overarching theoretical categories). This enhances the traceability of the analysis and strengthens methodological rigor.

- Integration of Induction and Abduction: While classical Grounded Theory primarily follows an inductive approach (where theories emerge solely from data), the Gioia-Methodology integrates both inductive and abductive elements. This means that existing theories are considered during the 2nd-Order Analysis to better contextualize emergent concepts within ongoing academic discussions.

- Simultaneous Consideration of Practice and Theory: The methodology incorporates both the perspectives of study participants (1st-Order Concepts) and the scientific interpretation by researchers (2nd-Order Themes). This balance ensures that findings remain both practically relevant and theoretically sound.

- Greater Acceptance within Academic Community: Gioia specifically developed this approach for management and social sciences to make qualitative research more transparent and rigorous for top-tier journals. The visual representation of the data structure and the iterative analysis process enhance methodological transparency, increasing its recognition within the academic community.

Outlook

Since 2016, there has been a significant increase in citations of the Gioia Methodology in academic publications. This trend suggests that the approach is increasingly establishing itself as a recognized method in qualitative research. The growing reception in leading academic journals can be seen as an indication of rising acceptance and validation by the scientific community. It remains intriguing to observe how the method continues to evolve in new disciplines and its combination with other qualitative approaches to meet the increasing demands for methodological transparency and reproducibility in qualitative research.

Key publications

References

Gioia, D. A., & Chittipeddi, K. (1991). Sensemaking and sensegiving in strategic change initiation. Strategic management journal, 12(6), 433-448.

Gioia, D. A., Thomas, J. B., Clark, S. M., & Chittipeddi, K. (1994). Symbolism and strategic change in academia: The dynamics of sensemaking and influence. Organization science, 5(3), 363-383.

Gioia, D. A., & Thomas, J. B. (1996). Identity, image, and issue interpretation: Sensemaking during strategic change in academia. Administrative science quarterly, 370-403.

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational research methods, 16(1), 15-31.

Gioia, D. (2021). A systematic methodology for doing qualitative research. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 57(1), 20-29.