Qualitative Content Analysis

Quantitative - Qualitative

Deductive - Inductive

Individual - System - Global

Past - Present - Future

In short: In this article, we aim to present and compare the two well-known approaches to conducting qualitative content analysis developed by Philipp Mayring and Udo Kuckartz. This article builds on the prior knowledge provided in the article on content analysis.

Contents

Background

Qualitative content analysis represents a variant of content analysis alongside quantitative content analysis. However, there is no single "Qualitative Content Analysis", but rather many different approaches of it. When engaging with the method of qualitative content analysis in German-speaking contexts, one is very likely to encounter two names: Philipp Mayring and Udo Kuckartz. Both authors have published well-established and widely cited works on qualitative content analysis, outlining different variations of the method. Among these, the thematic analysis (dt. inhaltlich-strukturierende Inhaltsanalyse) can be considered the central variant of qualitative content analysis. In this article, we will present both approaches in turn, compare them, and highlight some differences. Our aim is to provide guidance for anyone currently wondering which of the approaches might be the best to pursue.

What the method does

Mayring

Philipp Mayring established and popularized qualitative content analysis in German-speaking contexts with his book published in 1983, now available in its 13th edition. According to Mayring, qualitative content analysis is a structured, qualitative social science research method for analyzing text-based data. He assumes that recorded communication represents a complex system of meaning that can be broken down into smaller units. The goal of the method is, therefore, to extract relevant information and organize it into categories to facilitate interpretation. The analysis must be systematic, following a set of rules and guided by theory, with the aim of drawing conclusions about specific aspects of communication.

The core principles of Mayring's content analysis can be described as follows:

The foundation of the analysis is textual material, which is examined and interpreted within its communicative context. This is done according to a predefined procedural model, which can be individually adapted to the developed research question but still ensures a systematic approach. Inpractice, this means, e.g. determining in advance how the material will be approached, which parts will be analyzed in sequence, and whatconditions must be met to proceed with coding. This systematic, rule-based approach is intended to ensure traceability and verifiability, which form the basis of the social science research quality criteria of reliability and validity. A central characteristic of qualitative content analysis is the division of a text into categories. For this purpose, a code system must be developed, which can be done either inductively or deductively. Another important feature of qualitative content analysis is its theoretical grounding. The state of research on the subject and comparable areas of study should systematically inform all procedural decisions. Thus, the entire analysis is guided by a theoretically grounded research question. A theoretical perspective can and should also be incorporated into the development of the code system and the evaluation of results. For example, when developing the code system, established categories from studies in the specific subject area can be utilized. A final central feature of qualitative content analysis is the emphasis on quality criteria such as objectivity, reliability, and validity. In Mayring’s framework, intercoder reliability which refers to the degree of agreement or consistency between two or more independent coders when they analyze the same data using a predefined coding scheme holds particular importance.

Mayring describes qualitative content analysis using a total of eight different techniques. The three main forms are summary, explication, and structuring. In this article, we will focus particularly on structuring analysis, as it represents the most central form of analysis.

For the summary technique, the aim is to reduce the material to its essential content. The goal of this analysis is to condense the material in such a way that the key contents are preserved while creating a manageable corpus through abstraction that still reflects the original material. This approach to content analysis is primarily inductive. In explicative content analysis, the focus is on expanding the textual material with additional material to improve understanding. The goal of the analysis is to provide supplementary material for individual, unclear parts of the text (e.g., terms, sentences) to explain, interpret, and elaborate on these text passages.

Finally, structuring content analysis revolves around filtering specific aspects from the analysis material. This approach is more deductive in nature. The goal of the analysis is to extract specific content areas from the corpus material based on predefined organizational criteria, provide a cross-section of the material, or assess the material according to certain criteria. This is achieved through the application of a code system. All text components addressed by the categories are then systematically extracted from the material. For this purpose, each category must be precisely defined, subcategories may need to be developed, and examples should be used to concretely characterize them. After the analysis is complete, the extracted text material can be summarized for each subcategory and category.

The following section describes the approximate procedure for a structuring content analysis, which can also be followed in the accompanying figure.

The first step is defining the text material. In many cases, this involves selecting a sample from a larger pool of material. According to Mayring, it is important to ensure that the sample size is sufficiently representative and that the sample is selected using a specific model, such as random sampling. The next step is the analysis of the circumstances of origin. This involves providing a detailed description of who produced the material and under what conditions it was created. Important details include the author and the context of creation. This is followed by a description of the formal characteristics of the material, such as the format in which the material is presented. After summarizing the corpus material, a research question is defined, along with its theoretical foundation and its connection to the analysis material. In the next step, an analysis technique—summary, explication, or structuring—is selected, which then determines the subsequent course of the content analysis. This is followed by the creation of a code system, which is used to examine the analysis material. These categories are developed through an interplay between theory (the research question) and the actual material. This does not have to be a linear process and can be revised and re-evaluated during the analysis. In the structuring content analysis, criteria often need to be developed in advance—typically based on a specific theoretical approach related to the research topic—according to which the analyzed material is evaluated. The category system is documented in a code book, which includes the definition of the categories, coding rules, and examples. These elements help to distinguish individual categories from one another and ensure clear and consistent categorization.

Before coding begins, it is important to define the units of analysis. This includes distinguishing between the coding unit, context unit, and recording unit. The recording units are the materials analyzed sequentially, such as individual interviews or newspaper articles. The coding unit is the smallest text component to be coded, such as a word or a sentence. The context unit is the largest text component to be coded, such as a paragraph. The corpus material is then systematically examined and sorted according to the predefined categories. During this process, changes to the code system may occur, which must be transparently documented. If the code system is updated, the entire material must be recoded using the revised system.

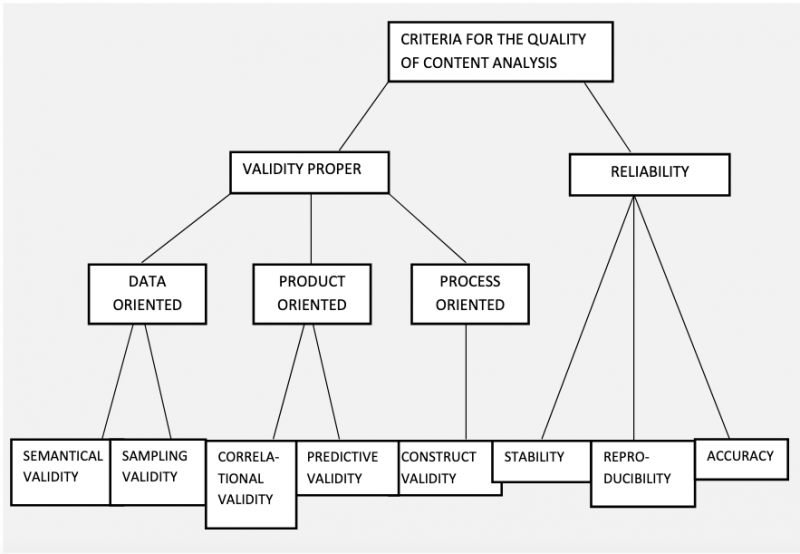

After the coding process is complete, the results are evaluated and interpreted in relation to the research question. The final step of the content analysis involves ensuring the quality criteria are met. Mayring derived eight specific quality criteria for qualitative content analysis from the classical criteria of validity (Does the method measure what it is intended to measure?) and reliability (Is the method reliable when applied repeatedly?). These criteria are outlined in Figure 2. Overall, the aim is to ensure intersubjective traceability by transparently documenting the research process, the derivation of findings, and the interpretation of results, with evidence clearly anchored in the material.

Kuckartz

The qualitative content analysis developed by Udo Kuckartz was published approximately 30 years after Mayring’s work and thus builds upon it. Kuckartz is also the creator of the software MAXQDA, which is why his procedural steps are more closely aligned with the use of such software. Kuckartz’ approach can therefore be seen as a modernization of qualitative content analysis. According to Kuckartz, qualitative content analysis is defined as the systematic and methodologically controlled scientific analysis of the content of communication, such as texts, images, films, etc. Similar to Mayring, the core of qualitative analysis lies in the deductively or inductively developed categories used to code all material relevant to the research question(s). The analysis is primarily qualitative in nature but can also incorporate quantitative statistical evaluations.

Kuckartz distinguishes between three fundamental procedural models for content analysis: thematic, evaluative, and type-building content analysis. As with Mayring earlier in this article, we will focus on Kuckartz’s thematic analysis in our description, as it is the most widely used form and thus serves as the core method for many content-analytic procedures. In the thematic analysis, the analysis of material is conducted based on a thematic organization. This means that the data is analyzed in a content- and topic-oriented way with the aim of identifying overarching themes and subthemes. Unlike Mayring's approach, the development of categories can be conducted both inductively and deductively. Evaluative analysis, on the other hand, focuses on the assessment, classification, and evaluation of the material. This method is particularly suitable for research interests that aim to assess attitudes or opinions on specific topics. The material is categorized and evaluated accordingly. Type-building analysis often builds on the two previously described methods and aims to group cases into similar patterns, thereby forming distinct types that highlight meaningful differences.

Before we describe the process of thematic structuring in content analysis, we will briefly address three important aspects of Kuckartz’ approach: his distinction between different units of analysis, the different types of categories, and the significance of a code system. Kuckartz, like Mayring, differentiates between several units that play a role during the analysis: The selection unit (dt. Auswahleinheit) refers to the fundamental units of content analysis—essentially, the cases selected for qualitative content analysis. These could include, for example, interviewed individuals, specific issues of a magazine, or parliamentary speeches from a particular time period. The analysis unit (dt. Analyseeinheit) is closely related to the selection unit and refers to the specific elements targeted for analysis. A single selection unit can contain multiple analysis units. For instance, within one magazine issue, several articles may be chosen for analysis. The coding unit, similar to Mayring’s approach, represents the smallest unit that is coded or assigned to a category. This could be a single word, sentence, or even an entire paragraph. Finally, the context unit refers to additional text passages that may need to be marked during the analysis to help contextualize or understand the respective analysis or coding unit.

Unlike Mayring, Kuckartz distinguishes between different types of categories, regardless of whether they are developed inductively or deductively. These categories are a theoretical differentiation. You do not have to analyze your material according to them nor are there necessarily all categories in your data. The six different types can be found in Table 1.

| Type | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| formal category | Data and information about the analysis unit | duration of the interview, date |

| factual category | easily identifiable facts in the data | place of living, profession, event |

| natural category | similar to In-Vivo-Codes in Grounded Theory; derived from terms in the corpus material | words used by research participants |

| thematic category | occurring most often; describe a specific theme/argument/aspect in the data | political engagement, consumption behavior, environmental knowledge |

| analytical/theoretical category | more abstract than thematic categories - results of an intensive examination of the data; can be developed on the basis of existing theories | self-efficacy, populism, environmental justice |

| evaluative category | has sub-categories, which follow an ordinal scale; used to evaluate the corpus material; are used in evaluative content analysis | agrees - rather agrees - neutral - rather disagrees - disagrees; low - medium - high |

The foundation of qualitative content analysis according to Kuckartz, similar to Mayring, is the code system. This system encompasses all categories and can be organized in three different forms: as a linear list, a hierarchy, or a network. A linear list is a simple arrangement of categories, all on the same level, such as "environmental knowledge," "environmental attitudes," and "environmental behavior". A hierarchical code system, on the other hand, consists of multiple levels of overarching and subordinate categories. For example, the category "environmental behavior" might include subcategories such as "energy behavior," "mobility behavior," "consumption behavior," and "recycling behavior". In this case, the terms main (or overarching) categories and subcategories are used. Beyond considering how categories relate to one another, it is also important to develop category definitions. These definitions not only increase the transparency of the analysis process for the scientific community but also serve as concrete instructions for other potential coders involved in the project.

Having now described the key conceptual aspects of Kuckartz’ content analysis, we move on to the process of the thematic content analysis, which is visualized in Figure 3. The first step in the analysis process is the selection of the material to be analyzed. This could include pre-existing text material or, for instance, interviews that still need to be transcribed into written form. Once the corpus material is finalized, the next step is initiating text work. This initial exploration can provide valuable insights for designing the code system, identifying relevant topics and aspects, and generating ideas for further analysis. For example, significant text passages can be highlighted, initial observations and analysis ideas can be noted in memos, or brief case summaries can be written. Memos can be compared to sticky notes; they represent the thoughts, ideas, and hypotheses recorded by researchers during the analysis process. These can be handwritten in the margins of the text being analyzed or inserted directly into the appropriate places within the MAXQDA software. Case summaries are particularly useful when dealing with a manageable number of analysis units. The aim here is to capture the central characteristics of each individual case as concisely and textually close to the source as possible.

After the initial text work, the next step is open coding. Here, approximately 20 percent of the total material corpus is reviewed, and text excerpts related to specific topics are marked and assigned a code. In the simplest case, only the term or core idea of the statement that leads to the coding is recorded. Alternatively, a formal criterion—such as a sentence or paragraph—can be defined as the unit to be coded. In most cases, especially when working with QDA software, it is recommended to code units of meaning, i.e., complete statements that remain understandable even when analyzed outside their original context. The categories are derived directly from the data (inductive) rather than predetermined. However, the research question can often provide guidance, as it may suggest initial categories that are expected to emerge during the analysis. The new categories are briefly described and documented in memos. Kuckartz illustrates this step with an example study in which open-ended interviews asked participants about what they perceive as the world’s biggest problems. From this, he deduces that the category "Biggest World Problems" represents a main category for analysis.

After open coding, the next step is coding with the main categories. In this phase, the entire text is segmented according to the main categories, line by line. Text passages that are not meaningful or not relevant to the research question remain uncoded. Once the text has been fully coded, subcategories are inductively developed within each main category. To achieve this, the materials within a given category are analyzed to identify additional subcategories that help further organize the material. It can be useful to create a list or table of all text passages coded under a specific main category and attempt to organize or systematize them according to relevant dimensions or aspects of the main category. Similar text passages can be grouped into more general subcategories. For these new subcategories, definitions must also be formulated, and example quotes from the material should be identified. Afterward, the entire material is recoded using the now complete code system. During this process, it is possible for a single text passage to address multiple main and subcategories. As a result, a text passage can be assigned to multiple categories. In the final step, the analysis of the categories is completed. This involves determining relationships between the categories and visualizing and describing the results of each category.

Strengths & Challenges

According to Schreier (2014), who compared different types of content analysis on a conceptual level, the structuring, respective thematic, analyses described by Philipp Mayring and Udo Kuckartz represent the central variants of qualitative content analysis. The approaches of both authors overlap significantly, and the core goal of the analysis—namely, identifying and conceptualizing selected content aspects in the material and systematically describing the material with the help of a code system—aligns between the two. However, there are subtle differences between their approaches (see Table 2), particularly regarding the basis for the categories (deductive or inductive). For instance, Mayring emphasizes the necessity of a theoretical foundation for the categories, while Kuckartz does not make definitive statements about the extent to which categories should be theory-driven or inductively developed from the material. For Kuckartz, different combinations of a mixed deductive-inductive approach are possible. Unlike Mayring, he is significantly more open to inductive category formation and, for example, also recommends the use of other methods such as Grounded Theory.

Another distinction concerns the nature of the categories. While Kuckartz differentiates between various types of categories (thematic, evaluative, formal, etc.), Mayring does not make this distinction. A further difference lies in the importance of quality criteria for the results of the analysis. Mayring discusses these criteria extensively and particularly emphasizes the use of quantitative intercoder reliability as a quality criterion. Kuckartz, on the other hand, is more critical of calculating this value for qualitative data. Instead, he distinguishes between internal study quality (e.g., reliability, dependability, auditability, rule-based procedures, intersubjective traceability, credibility) and external study quality (e.g., issues of transferability and generalizability). These differences, however, pertain only to implementation strategies and not to fundamental divergences in the approach.

| Mayring | Kuckartz | |

|---|---|---|

| building of categories | rather deductive | both inductive & deductive |

| types of categories | no differentiation | differentiation in six types |

| quality criteria | very important, especially intercoder reliability (quantitative measurement) | important, rather qualitative measurements such as a transparent process |

Normativity

The choice between qualitative content analysis according to Mayring and Kuckartz depends on several factors, particularly the research question, theoretical foundation, and the desired level of systematization in the analysis.

Qualitative content analysis according to Mayring is particularly suitable when:

- A theoretical foundation for the categories is desired. Mayring emphasizes deductive category development, meaning that categories can be derived from theory in advance.

- A rule-based, structured procedure is required. The approach follows a precise process with clearly defined steps.

- Intercoder reliability plays a significant role. Mayring places strong emphasis on quality criteria such as intercoder agreement, more so than Kuckartz.

- A combination of qualitative and quantitative elements is beneficial. His method allows for quantitative evaluations (e.g., frequency analyses).

Qualitative content analysis according to Kuckartz is the better choice when:

- Greater openness to inductive category development is desired. Kuckartz allows for a stronger combination of deductive and inductive categories.

- Software-supported analysis is a priority. The method is well-suited for digital tools such as MAXQDA.

- Different types of categories are to be used. Kuckartz differentiates between thematic, evaluative, and formal categories, for example.

- An exploratory approach is pursued. This method is particularly suitable for research questions that are less theoretically pre-structured.

The decision depends on whether you prefer a deductive, structured, and theory-based analysis (Mayring) or a more flexible, exploratory approach (Kuckartz).

Outlook

Another example of a systematic approach to analyzing qualitative data is the Gioia Methodology. The method is inspired by the methodology of Grounded Theory, developed by Glaser and Strauss. This approach represents a systematic method for inductive concept development, balancing the often conflicting goals of developing new concepts inductively while meeting the high standards of rigor required by top journals.

In the Gioia Method, data is progressively distilled and theoretically abstracted using 1st-order concepts, 2nd-order themes, and aggregate dimensions, ultimately resulting in the identification of the 3-5 most important overarching themes that summarize the data material in relation to a specific research question. The Gioia Method is particularly suitable for research projects aiming to investigate a topic inductively, as opposed to approaches like Mayring's, where theoretical assumptions are often established beforehand.

Key publications

Kuckartz, U. & Rädiker, S. (2019). Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA: Text, Audio, and Video. Springer.

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt, Austria.

Mayring, P. (2019). Qualitative content analysis: Demarcation, varieties, developments. Forum: Qualitative social research 20(3). Freie Universität Berlin.

References

Kuckartz, U. (2014). Qualitative text analysis: A guide to methods, practice and using software. Sage.

Kuckartz, U. (2016). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung (3., überarbeitete Auflage). Grundlagentexte Methoden. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Juventa.

Mayring, P. (2022). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken (13. überarbeitete Auflage). Weinheim: Beltz Verlagsgruppe.

Schreier, M. 2014. Varianten qualitativer Inhaltsanalyse: Ein Wegweiser im Dickicht der Begrifflichkeiten. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung 15(1). Artikel 18.