Difference between revisions of "Semi-structured Interview"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[File:Qual dedu indu indi pres.png|thumb|right|[[Design Criteria of Methods|Method Categorisation:]]<br> | + | [[File:Qual dedu indu indi past pres futu.png|thumb|right|[[Design Criteria of Methods|Method Categorisation:]]<br> |

Quantitative - '''Qualitative'''<br> | Quantitative - '''Qualitative'''<br> | ||

'''Deductive''' - '''Inductive'''<br> | '''Deductive''' - '''Inductive'''<br> | ||

'''Individual''' - System - Global<br> | '''Individual''' - System - Global<br> | ||

| − | Past - '''Present''' - Future]] | + | '''Past''' - '''Present''' - '''Future''']] |

'''In short:''' Semi-structured Interviews are a form of qualitative data gathering through loosely pre-structured conversations with Interviewees. For more Interview forms, and more on Interview methodology in general, please refer to the [[Interviews|Interview overview page]]. | '''In short:''' Semi-structured Interviews are a form of qualitative data gathering through loosely pre-structured conversations with Interviewees. For more Interview forms, and more on Interview methodology in general, please refer to the [[Interviews|Interview overview page]]. | ||

Revision as of 15:02, 26 July 2024

Quantitative - Qualitative

Deductive - Inductive

Individual - System - Global

Past - Present - Future

In short: Semi-structured Interviews are a form of qualitative data gathering through loosely pre-structured conversations with Interviewees. For more Interview forms, and more on Interview methodology in general, please refer to the Interview overview page.

Contents

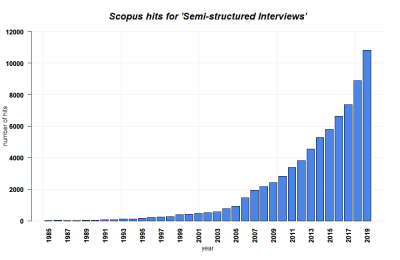

Background

"Interview methodology is perhaps the oldest of all the social science methodologies. Asking Interview participants a series of informal questions to obtain knowledge has been a common practice among anthropologists and sociologists since the inception of their disciplines. Within sociology, the early-20th-century urban ethnographers of the Chicago School did much to prompt interest in the method.” (1) Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss are crucial figures in this regard, developing the Grounded Theory approach to qualitative data analysis during the 1960s. With their 1967 landmark book (see Key Publications) they paved the road towards an integration of methodologically building on Interviews, thereby creating a whole new area of research in sociology and beyond. Building on their proposal, yet also before, several publications contributed to a proper understanding of Interview methodology and how to best conduct Interviews (see Key Publications). Today, qualitative Interviews are used mostly in gender studies, social and political studies as well as ethnographics (2, 8).

What the method does

- Interviews are a form of data gathering. They can be conducted in direct conversation with individuals or groups. This is also possible online or via the phone (1, 2). It is possible for more than one researcher to conduct the Interview together (2). The necessary equipment includes an Interview guide that helps ask relevant questions, a recording device and paper & pencil or a computer for note taking during the Interview.

- Semi-structured Interviews can be used for many research purposes, including specialized forms. Among the latter, more common versions include the expert Interview where the Interviewee is a person of special knowledge on the topic, the biographical Interview that serves to investigate a life-history, the clinical Interview that helps diagnose illnesses, and the dilemma-Interview that revolves around moral judgements (8).

- "Interview methodology is particularly useful for researchers who take a phenomenological approach. That is, they are concerned with the way in which individuals interpret and assign meaning to their social world. It is also commonly used in more open-ended inductive research whereby the researcher observes specific patterns within the Interview data, formulates hypotheses to be explored with additional data, and finally develops theory." (1) Interviews allow the researcher to gain insight into understandings, opinions, attitudes and beliefs of the Interviewee (2).

How to do a semi-structured Interview

Creating the Interview guideline

In a semi-structured Interview, the researcher asks one or more individuals open-ended questions. These questions are based on and guided by an Interview guide that is developed prior to the conduction of the Interview. The Interview guide is based on the research intent and questions, and can be informed by existing literature: the researchers think of the information they need to gather from the Interviews to answer the research questions, and develop the Interview guide accordingly. The Interview guide thus contains keywords or issues that need to be covered during the Interview in order to answer the research questions. However, in this form of Interviews, there is still room for new topics, or focal points to existing questions, emerging during the Interview itself. The guide, therefore, ought to be as "open as possible, as structuring as necessary" (Helfferich 2019, p.670). The contents are structured in broad overarching categories (dimensions) and subordinate, more precise elements (3, 1). To create an Interview guide, first, questions relevant to the research interest are collected in an unstructured manner. After this, they are sorted according to their cohesiveness (Helfferich C. 2019, p.675f). The Interview guide should be tested before conducting the first Interviews that ought to be analyzed. In these pre-tests with peers or test subjects, the length of the Interview guide, the cohesiveness and viability of the questions, and the overall structure of the guide can be checked and possibly refined.

Conducting the Interview

Before the start of the Interview, the Interviewer lets the Interviewee sign a Consent Form, guaranteering voluntary participation in the research. The Interviewer should provide Full Disclosure (information about the main goal of the research and further use of the information), confidentiality of the Data as well as the right of the Interviewees to review the results before publication and to withdraw from the Interview if they feel uncomfortable.

The Interviewer then starts posing general questions based on the overarching dimensions of the Interview guide. They are answered openly by the Interviewee and can be supported by asking for more details. Subsequently, more detailed questions based on the subordinate elements are posed to gather knowledge on previously un-addressed issues (5). Commonly, although not always, the Interviewer is also the researcher, which provides him/her with a role that can be potentially conflicting: He/she/they can decide ad hoc to change the order of questions, pre-empt elements that were designated for later questioning or add questions based on insights that arise during the Interview (1). The Interviewer may encourage the Interviewee to extend on his/her/their remarks but also guide the Interview back to the pre-determined structure in case the Interviewee digresses (3). At the end of the Interview, all subordinate aspects of the Interview guide should be covered (3). Additional questions may be asked if they emerge during the Interview, but should not replace previously planned questions from the guide.

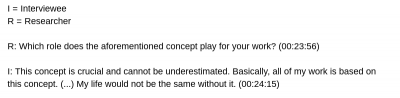

Transcribing the Interview

The Interview should be video- or audio-recorded for later transcription. This transcription is preferably done by writing down the recorded speech either word by word (denaturalism) or including stutters, pauses and other idiosyncratic elements of speech (naturalism). The chosen approach depends on the research design and purpose. In any case, the form of transcription should not impose too much interpretation upon the Interview data, and allow for intersubjective data readibility (7). The text may be structured and punctuations may be added to improve legibility. For ethical reasons, the identity of the Interviewee should be secured in the transcribed text (7). To allow for quotations, the lines of the transcript should be numbered or time codes should be added at the end of each paragraph (6). The subsequent analysis of the gathered data relies on this transcription. For more on this step, please refer to the entry on Transcribing Interviews.

Strengths & Challenges

- Due to the structure of the Interview procedure, the Semi-structured Interview allows for comparability of the results while ensuring openness. Thereby, it allows for the testing of existing hypotheses as well as the creation of new ones (3).

- Compared to the more restricted standardized format of surveys, the qualitative Interview allows for an open collection and investigation of self-interpretations and situational meanings on the part of the Interviewees. This way, theories from psychology and sociology can more easily be empirically tested (3).

- At the same time, due to this focus on the subjective position of the Interviewee with regards to his/her feelings, attitudes and interpretations, the results gathered in qualitative Interviews are not as easily generalizable and more open to criticism than data gathered in quantitative surveys (2).

- Language barriers may challenge the understanding of the Interviewees' statements during the Interview and in the transcription process.

- Pitfalls during the Interview: It is crucial that the Interviewer is well-acquainted with the theoretical approach and design of the research. Only then can he/she assess when to depart from the previously developed questions, ask follow-up or intentionally open questions (8). This process imposes high demands on the Interviewer. The Interviewer must remain attentive and flexible throughout the Interview in order to make sure all relevant aspects of the Interview guide are profoundly answered. The quality and richness of the data depend on the proficiency in this process (1). In addition, the Interviewer must make sure not to impose bias on the Interviewee. Therefore, he/she should not ask closed yes/no-questions or offer answers for the Interviewee to choose from. The Interviewer should not be impatient while listening to the Interviewee's narration. Answers should not be commented or confirmed. The questions should not be judgemental, unexpected or incomprehensible to the Interviewee (3, 5). It is thus recommendable that the Interview be rehearsed and the Interview guide be tested before the first real Interview so as to ensure the quality of the Interview conduction. Lastly, the issue of Interviewee fatigue - i.e. the Interviewee becoming tired of overly long Interviews, which may lead to a decline of the quality of the responses - should be counteracted by limiting the amount of questions in the Interview guide and thus the length of the overall Interview.

- The amount and depth of data that is gathered in long Interviews prohibits a big sample size. Also, the more extensive the Interview is, the longertakes the transcription process. Especially longer Interviews cannot be replicated endlessly, as opposed to the huge number results possible with standardized surveys. Semi-structured Interviews therefore tend to medium-sized samples (1, 2).

Normativity

Connected methods

- Qualitative Interviews can be used as a preparation for standardized quantitative Interviews (Survey), Focus Groups or the development of other types of data gathering (2, 8). To this end, they can provide an initial understanding of the situation or field of interest, upon which more concrete research elements may follow.

- A literature review may be conducted in advance to support the creation of the Interview guide.

- A Stakeholder Analysis may be of help to identify relevant interviewees.

- The transcripts ought to be analysed using a qualitative / quantitative form of content analysis (e.g. with MAXQDA) (1).

Everything normative related to this method

- Quality criteria: The knowledge gathered in qualitative Interviews, as in all qualitative research, is dependent on the context it was gathered in. Thus, as opposed to standardized data gathering, objectivity and reliability cannot be valid criteria of quality for the conduction of qualitative Interviews. Instead, a good qualitative Interview properly reflects upon the subjectivity involved in the data gathering process and how it influences the results. It is therefore crucial to transparently incorporate the circumstances and setting of the Interview situation into the data analysis. The quality criteria of validity, i.e. the extent to which the gathered data constitutes the intended knowledge, must be approached by the principles of openness and unfamiliarity. An open approach to the Interview ensures a valid understanding of the Interviewee's subjective reality (4).

- Ethics: As indicated throughout the text, a range of ethical principles should guide the Interviewing process. These include that Interviewees should be informed about the goal of the research and the (confidential) use of their data and statements. The creation of recordings requires consent. Interviewees should be allowed to review and withdraw statements, and if desired, they should be credited for their participation in the Interviews.

- The sampling strategy may heavily influence the gathered data, with snowballing- or opportunistic sampling leading to potential bias in the Interviewee sample. The sample size depends on the intended knowledge in the first place. While more structured, systematic approaches (see Survey) need bigger sample sizes from which a numerical generalization may be done, more qualitative approaches typically involve smaller samples and generalization of the gathered data is not the researcher's main goal (2).

Key publications

Fielding, Nigel G., ed. 2009. Interviewing II. London: SAGE.

- A four-volume collection of essays of which the wide-ranging contributions comprehensively cover all the theoretical and practical aspects of Interviewing methodology.

Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. 1967. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

- The principles of Grounded Theory were first articulated in this book. The authors contrast grounded theories derived directly from the data with theories derived from a deductive approach.

Patton, Michael Q. 2002. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3d ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, and London: SAGE.

- In chapter 7, Patton provides a comprehensive guide to qualitative interviewing. This chapter highlights the variations in qualitative interviews and the interview guides or schedules that can be used. It provides a very useful guide as to how to formulate and ask questions and offers practical tips about recording and transcribing interviews. The chapter also covers focus groups, group interviews, ethics, and the relationship between researcher and interview participants.

Helfferich C. Leitfaden- und Experteninterviews. In: Baur N., Blasius J. (Hrsg.) 2019. Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung. Springer VS Wiesbaden. 669-685.

- A brief, but precise description of the basics of interview conduction. The chapter includes definitions, thoughts on the interview situation, a guide to interview guide creation and remarks on expert interviews in German language.

Widodo, H.P. 2014. Methodological Considerations in Interview Data Transcription. International Journal of Innovation in English Language 3(1). 101-107.

- Includes considerations on data management and transcription of interview data.

Whyte, William Foote. 1993. Street corner society: The social structure of an Italian slum. 4th ed. Chicago and London: Univ. of Chicago Press.

- The appendix describes in great detail how Whyte carried out his ethnographic research. He writes about how he had to learn not only when it was appropriate to ask questions, but also how to ask those questions—and that, once he was established in the neighborhood, much of his data was gathered during casual conversations.

Bryman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods. 4th Edition. Oxford University Press.

- An all-encompassing guide to the basics of social science research, including insights into interview methodology.

References

(1) Hamill, H. 2014. Interview Methodology. in: Oxford Bibliographies. Sociology.

(2) Arksey, H. Knight, P. 1999. Interviewing for Social Scientists. An Introductory Resource with Examples. SAGE Publications, London.

(3) Rager, G., Oestmann, I., Werner, P. Leitfadeninterview und Inhaltsanalyse. 1. Das Leitfadeninterview. 35-43. In: Viehoff, R., Rusch, G., Segers, R.T. 1999. Siegener Periodicum zur Internationalen Empirischen Literaturwissenschaft (SPIEL). Heft 1. Europäischer Verlag der Wissenschaften.

(4) Helfferich C. Leitfaden- und Experteninterviews. In: Baur N., Blasius J. (Hrsg.) 2019. Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung. Springer VS Wiesbaden. 669-685.

(5) Helfferich, C. 2011. Die Qualität qualitativer Daten. Manual für die Durchführung qualitativer Interviews. 4th edition. Springer VS Wiesbaden.

(6) Dresing, T., Pehl, T. 2015. Praxisbuch Interview, Transkription & Analyse. Anleitungen und Regelsysteme für qualitativ Forschende. 6th edition.

(7) Widodo, H.P. 2014. Methodological Considerations in Interview Data Transcription. International Journal of Innovation in English Language 3(1). 101-107.

(8) Hopf, C. Qualitative Interviews: An Overview: In: Flick, U. von Kardorff, E. Steinke, I. (eds). 2004. A Companion to Qualitative Research. SAGE Publications, London. 203-208.

The author of this entry is Christopher Franz.