Difference between revisions of "Living Labs & Real World Laboratories"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

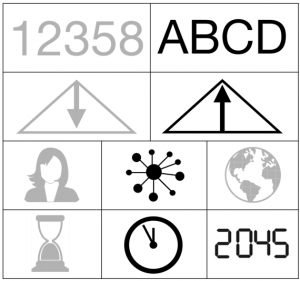

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:Qual indu syst pres futu.png|thumb|right|[[Design Criteria of Methods|Method Categorisation:]]<br> |

| − | + | Quantitative - '''Qualitative'''<br> | |

| − | + | Deductive - '''Inductive'''<br> | |

| − | + | Individual - '''System''' - Global<br> | |

| − | + | Past - '''Present''' - '''Future''']] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

'''Annotation:''' This entry deals with two concepts: Living Labs as well as Real-World Laboratories. While these are not strictly scientific methods as much as they are settings and modes, they shall be presented here in order to highlight their unique approach to scientific inquiries. Further, while both concepts are closely related, they are distinct in various aspects. Because of this, their description will be done separately where necessary and jointly where appropriate. | '''Annotation:''' This entry deals with two concepts: Living Labs as well as Real-World Laboratories. While these are not strictly scientific methods as much as they are settings and modes, they shall be presented here in order to highlight their unique approach to scientific inquiries. Further, while both concepts are closely related, they are distinct in various aspects. Because of this, their description will be done separately where necessary and jointly where appropriate. | ||

Latest revision as of 11:23, 18 March 2024

Quantitative - Qualitative

Deductive - Inductive

Individual - System - Global

Past - Present - Future

Annotation: This entry deals with two concepts: Living Labs as well as Real-World Laboratories. While these are not strictly scientific methods as much as they are settings and modes, they shall be presented here in order to highlight their unique approach to scientific inquiries. Further, while both concepts are closely related, they are distinct in various aspects. Because of this, their description will be done separately where necessary and jointly where appropriate.

In short: Living Labs (and Real-World Laboratories) are research, innovation and learning environments that facilitate solution-oriented research.

Contents

Background

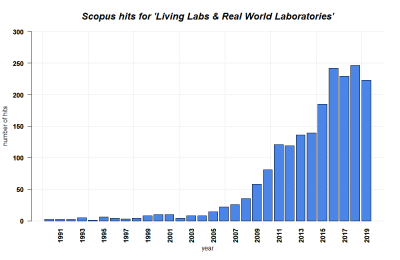

Both the Living Lab and the Real-World Laboratory approach are rather new research areas, emerging from the beginning of the 21st century.

The Living Lab (LL) started outside of academia, revolving around testing new technologies in home-like constructed environments in order to promote entrepreneurial innovation (1). In 2006, the European Network of Living Labs (EnoLL) was founded by the Finnish government, focusing on information and communication technologies and institutionalizing the concept (6, 9). The concept is therefore common predominantly in Europe but has also expanded to other geographical contexts during the last years (see Further Information). Living Labs have also emerged as a transdisciplinary scientific method, its applications going beyond product and service development for the sake of business: Living Labs have also been used in the fields of, among others, eco-design (4), IT (1), urban development (2), energy or mobility for the purpose of sustainable development.

The concept of Real-World Laboratories ('Reallabore') emerged around the same time, but was a scientific field from the beginning. It is most prevalent in German-speaking research communities that focus on sustainability and transdisciplinary transformative research (10). A broad set of RWLs have been set up in and supported by the German state of Baden-Württemberg since 2015 (14).

What the method does

Living Labs and Real-World Laboratories are research, innovation and learning environments. They share a variety of traits, but differ in crucial elements. Their characteristics will be described below.

The Living Lab "(...) has become an umbrella concept for a diverse set of innovation milieus (...)" (1, p.357) and has been described as a "rapidly diffusing phenomenon (...)" (6, p.139), indicating a lack of a distinct methodological conceptualization (9). The Living Lab has often been defined as both a methodology and the environment in which this methodology is being applied (1, 3, 6, 9). Generally, LLs revolve around the testing and implementation of new, marketable and standardized products and services that provide social or technological innovation (10). They experiment in settings with limited participation with these innovations and attempt to create generalizable insights. They do not necessarily contribute to transformative change.

Recurring fundamental elements of Living Labs include:

- ... the creation and testing of technological and/or social innovation (a service, a product, societal infrastructure) with the goal of solving real-world problems (1, 4, 6, 8)

- ... in a real-life test and experimentation environment (e.g. a house, a school, a city, a region or a virtual network) (1, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9)

- ... through the involvement and collaboration of diverse stakeholders with a common interest in the respective domain, including actors from business, government and academia as well as citizens (1, 7, 8, 9). The active, open and conscious co-involvement of 'users' of the respective service or product in the innovation process, equally among other stakeholders, constitutes a central idea of the Living Lab as opposed to more passive approaches where they are seen as subjects whose behavior is to be studied (1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9).

- ... with a technological component that allows for standardized, comparable feedback on the innovation process (1, 7, 9)

- A Living Lab can take between months and years (1, 9)

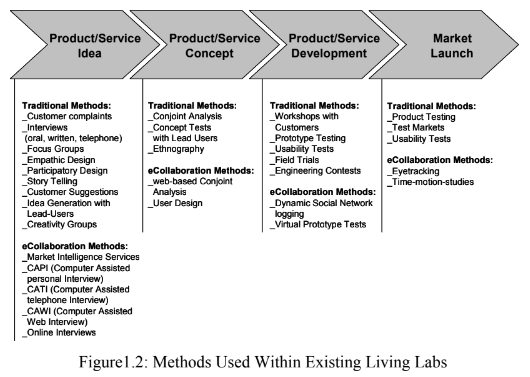

Within this co-creation approach, users can be involved on different stages of the innovation process: the ideation and conceptualization stage (co-creation), the implementation of the product or service or the evaluation (2, 7, 9). For each of these stages, a diverse set of potential methods exists that can be used to include the users' and stakeholders' perspectives (see Normativity). To provide the best results of the Living Lab, involvement on all of these stages should be combined in accordance with the specific goals and vision of the Living Lab (2, 9). However, an analysis of four Living Lab projects by Menny et al. (2018) indicates that the stage of co-creation is rarely achieved - most often, users are only included in the implementation or evaluation phase (2).

Real-World Laboratories, too, "(...) exhibit a broad and not clearly defined research format." (Schäpke et al. 2018, p.94). They are generally understood as research environments that complement transdisciplinary and transformation-oriented sustainability research by offering a real-world environment for experimentation and reflexive learning. RwLs attempt to close the gap between research and practice by combining scientific research with contributions to societal change in order to solve societally relevant problems (12, 13). This may help solve scientific problems, but also practical issues and fulfill educational purposes (13). RwLs are both interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary in that they strongly favor the involvement of various stakeholders from different scientific and non-scientific backgrounds that are relevant to the problem at hand. RwLs and Living Labs share the characteristics of stakeholder involvement and real-world experimentation, but focus more on the process of researching, learning and testing of new structures and transformative processes rather than on the implementation of a specific innovation.

Core characteristics of Real-World Laboratories are that (10, 13)

- ... they contribute to transformation by experimenting with potential solutions and support transitions by providing evidence for the robustness of solutions

- ... they deploy transdisciplinarity as the core research mode in order to "(...) integrate scientific and societal knowledge, related to a real-world problem" (Schäpke 2018 p.87). They "(...) can build on previous transdisciplinary process of, for instance, co-designing a shared problem understanding and related vision (...) or they can inclue these steps." (Schäpke 2018, p.87)

- ... they establish a culture of sustainability around the laboratory, stabilize the cooperation between the actors and empower the involved practitioners

- ... they therefore have a strong normative and ethical component and pursue to contribute to the common good

- ... they include experiments as a core research method which they provide concrete settings for, and which stakeholders are actively involved in (co-design and co-production)

- ... they attempt to create solution options that "(...) have a long-term horizion, potentially going beyond the existence of the lab" (Schäpke 2018, p.87)

- .... they have a strong educational aspect and support three levels of reflexive learning: individual competency, social learning and learning with regard to transdisciplinary collaboration

- ... learning outcomes are used to evaluate the research procedure, applied to improve the research process, and transferred to other transformation processes

- ... they create knowledge on and for transformative processes which consists of system knowledge, target knowledge and process knowledge

Apart from LL and RWL, there are further related approaches which should be mentioned:

- (Urban) Transition Labs are based on transition management and focus on developing new ideas, practices and structures to support transition processes (10). Guiding principles and future visions for the transition process are developed and translated into experiments through backcasting (10, p.88). They focus neither on transdisciplinary research processes nor on specific socio-technical innovations, but revolve around the conceptualization of broader socio-technical change, including social learning and empowerment processes.

- Transformative Labs focus on systemic human-environment connections that are neglected in other transition management approaches. They strongly acknowledge environmental feedbacks in the innovation process and attempt to change the system dynamics that created existent problems in the first place (10). They "(...) build on extensive pre-studies and collective system-analysis to develop prototypes of systemic innovations and awareness amongst participants that they are part of a system (reflexivity)" (Schäpke et al. 2018, p.94).

Strengths & Challenges

Living Labs

- The central element of the Living Lab - the co-involvement of 'users' at all stages of the development process - constitutes a distinctiveness of the method and provides specific advantages to the process (7). Instead of designing the product around the alleged needs of the users, the ideas and knowledge contributed by the users enable the developer (e.g. the company, the researchers) to more properly design their product / service according to the user's needs and desires (4, 6). The contextual knowledge gained in the real-world environment further facilitates the design process of the respective product or service (6, 7). This way, the risk of failure is decreased while the result better fits the user and supports sustainability, e.g. by reducing the rebound effect in eco-design (4).

- At the same time, this element poses challenges. First, it may be difficult to develop effective methods and business models to motivate individuals to participate in the Living Lab process during which they provide work and knowledge that should be compensated (1, 9). This collaboration between all the different stakeholders ought to be continuous to make the Living Lab successful (1, 7, 8). Also, the participants should depict a sufficiently diverse and realistic representation of the eventual group of 'users', which raises the question of how to gather participants for the Living Lab (1, 2, see Normativity). In this regard, a socially inclusive, high level of involvement may lead to higher engagement and better results of the overall process (2).

Real-World Laboratories

- RwLs highlight the need for profound participation and cooperation (11). Doing justice to the diverse roles, perspectives and intentions of the involved stakeholders requires a differentiated procedure, structure and choice of methodological approaches. Further, "[u]ndertaking collaborative, real-world experiments (...) often raises particular challenges regarding ownership, transparency, knowledge integration, and conflict management." (Schäpke 2018, p.87)

- The various kinds of intended knowledge raise a need for a highly reflexive application of methods. Another challenge in this regard is to balance the descriptive-analytical and the prescriptive research focus (10). "RwL approaches are subject to major challenges. These include high expectations (e.g., delivering evidence-based knowledge and governing societal change), blurring of boundaries and responsibilities due to the engagement of researchers in societal actions, and a lack of analytical distance in the research process between the researchers and their objects of investigation." (Schäpke et al. 2018, p.94)

- "A major challenge regarding research quality concerns the generation of generic and transferable insights from experiments in specific contexts, with many factors that are difficult to control" (Schäpke 2018, p.87) In order to provide transferable and scalable solutions, feasibility studies, comparisons of experiments between labs and the involvement of key actors from different scales are beneficial. However, this "(...) requires adequate project architectures and longer-term fuding, allowing for continuous experimentation and longitudinal evaluation. Transferability and scalability are particularly challenging and potentially limited due to the situatedness of RwLs" (Schäpke et al. 2018, p.87)

Normativity

Connectedness

As shown in the diagram below, the incorporation of user and stakeholder perspectives in Living Labs can take various methodological forms, including traditional scientific methods such as interviews or ethnographics as well as tools and methods originating from marketing and business.

RwLs can employ a variety of methods and combinations thereof, partly ones are developed specifically for the Real-World Laboratory context (13). Distinct methods of transdisciplinary research are listed in the TD entry.

Everything normative

- As with all transdisciplinary research methods, Living Labs and Real-World Laboratories have a highly normative component that relates to collaborating with real-world actors (see the TD entry). For the Living Lab, this is the case since it revolves around creating products and services that provide maximum suitability to the needs, desires and ideas of individuals. Living Labs are situated in the middle of the user involvement spectrum ranging from the user as the main creator to the user as a passive subject whose insights are introduced into the innovation process (3, 6)

- For RwLs, the transformative purpose raises questions of which kind of future scenario is desired by whom: "RwLs [Real-World Laboratories] become immersed in political and normative issues that science traditionally attempts to avoid. Correspondingly researchers take on new roles in addition to what is traditionally seen as research (i.e., producing knowledge), including acting as facilitators of the process, knowledge brokers, and change agents" (Schäpke et al. p.87)

- The selection of the participating individuals and stakeholders is a normative endeavour. An important notion in this regard is the question of an Open vs Closed format of user involvement - i.e. is everyone allowed to participate or only selected users and stakeholders? A closed format allows for more focused and in-depth feedback but requires the capacity to select individuals and limit access to the research environment. An open format, on the other hand, is simpler to implement and provides more diversity, but requires the capacity to filter results and manage the greater number of users (6).

- Both approaches serve as empowering environments for the individuals involved (1, 8, 10, 13). They can have educational impacts and enable citizens to participate in processes that influence their daily lives.

Outlook

- Being a rather young methodological approach, the Living Lab still lacks clear definitions and supporting concepts as well as robust and homogenous methodologies, methods and tools (1, 4, 9). The majority of theoretical publications include thoughts on how to locate the method within participatory design approaches, or descriptions of individual projects. Few peer-reviewed studies exist that provide an instructional, clear illustration of the method's elements (6, 9). This impedes its more wide-spread use of the approach but may also be seen as flexibility, displayed by the various applications and adaptations of the approach in an increasing amount of diverse contexts (5, see Further Information).

- Real-World Laboratories are yet to be established in the realm of the other comparable approaches. They are not "(...) unique or completely new in what they pursue and in the ways they proceed. They are part of a larger development: the emergence of a family of transdisciplinary and experimental approaches to transformative research. (...) Current trends in funding programs and research collaborations provide space to further explore the potential of experimental approaches in transformative research. Long-term evaluation and comparisons will show which approaches or combinations are most promising, in terms of real-world sustainability transformation and acceleration in given contexts. (...) [T]he diverse emerging approaches may complement each other, rather than compete for being the “best” approach." RwLs "(...) have a lot to learn from the other approaches. (...) Their open approach may provide a suitable framework for combining different components of experimental transformative research. Thus, RwLs might contribute to building bridges between different styles of transformative research, the design and implementation of experiments, as well as the evaluation fo processes of learning and reflexivity." (Schäpke et al. 2018, p.95)

- "Despite the dynamic development of lab approaches in the last decades, their diffusion is still limited. The contribution of such approaches to societal transformation largely depends on them being embedded into a broader policy commitment to systemic change, as well as on the development of mechanisms to accelerate learning." (Schäpke et al. 2018, p.95) If their long-term establishment is supported, RwLs may provide an institutionalized frame for systematic transdisciplinary and transformative research and experimentation. In this regard, RwLs have the potential to support the further development of science-society collaborations and provide new ideas for academia (11). "On their own, lab approaches risk to have limited real-world impact. Creating some isolated space for experimentation, the significance of labs for societal transformation might remain limited by their own borders. It is thus important to complement lab approaches with broader policy commitments, if we want to harness the transformative potential of these approaches in the real world." (Schäpke et al. 2018, p.95)

Key Publications

- Veeckman, C. Schuurman, D. Leminen, S. Westerlund, M. 2013. Linking Livinb Lab Characteristics and Their Outcomes: Towards a Conceptual Framework. Technology Innovation Management Review 3(12). 6-15.

A more recent explanation of the concept and an analysis of four Living Labs with a focus on how their characteristics influenced their results.

- Schäpke, N. et al. 2018. Jointly Experimenting for Transformation? Shaping Real-World Laboratories by Comparing Them. GAIA 27(1). 85 – 96.

Presents and compares diverse approaches to transformative research.

- Defila, R. Di Giulio, A. Reallabore als Quelle für die Methodik transdisziplinären und transformativen Forschens - eine Einführung. in: Defila, R. Di Giulio, A. (eds). 2018. Transdisziplinär und transformativ forschen. Eine Methodensammlung. Springer VS.

A German summary of learnings and experiences made with Real-World Laboratories.

- Schwartz et al. 2015. What People Do with Consumption Feedback: A Long-Term Living Lab Study of a Home Energy Management System. Interacting with Computers 27(6). 551-576.

A Living Lab study on the topic of energy efficiency in households, conducted for 18 months in Germany. Data was collected through energy logs, interviews, surveys, observation and Grounded Theory

- Bernert, P. et al. 2016. Towards a Real-world Laboratory. A Transdisciplinary Case Study from Lüneburg. GAIA 25(4). 253-259.

A case study that presents the establishment of a RwL in Lüneburg.

References

(1) Bergvall-Kareborn, B. Stahlbröst, A. 2009. Living Lab: an open and citizen-centric approach for innovation. International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development 1(4). 356-370.

(2) Menny, M. Palgan, Y.V. McCormick, K. 2018. Urban Living Labs and the Role of Users in Co-Creation. GAIA 27. 68-77.

(3) Almirall, E. Lee, M. Wareham, J. 2012. Mapping Living Labs in the Landscape of Innovation Methodologies. Technology Innovation Management Review 2(9). 12-18.

(4) Liedtke, C. Welfens, M.J. Rohn, H. Nordmann, J. 2012. LIVING LAB: user-driven innovation for sustainability. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 13(2). 106-118.

(5) Niitamo, V.P. Kulkki, S. Eriksson, M. Hribernik, K. 2006. State-of-the-art and good practice in the field of living labs. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Concurrent Enterprising: Innovative Products and Services Through Collaborative Networks.

(6) Dell'era, C. Landoni, P. 2014. Living Lab: A Methodology between User-Centered Design and Participatory Design. Creativity and Innovation Management 23(2). 137-154.

(7) Hribernik, K. et al. 2008. Living Labs - A New Development Strategy. in: Schumacher, J. Niitamo, V.P. (eds.) 2008. European Living Labs - A New Approach for Human Centric Regional Innovation. Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, Berlin, Germany. 1-14.

(8) van der Walt, J.S. Buitendag, A.A.K. 2009. Community Living Lab as a Collaborative Innovation Environment. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology. Volume 6. 421-436.

(9) Veeckman, C. Schuurman, D. Leminen, S. Westerlund, M. 2013. Linking Living Lab Characteristics and Their Outcomes: Towards a Conceptual Framework. Technology Innovation Management Review 3(12). 6-15.

(10) Schäpke, N. et al. 2018. Jointly Experimenting for Transformation? Shaping real-world laboratories by Comparing Them. GAIA 27(1). 85 – 96.

(11) Defila, R. Di Giulio, A. Reallabore als Quelle für die Methodik transdisziplinären und transformativen Forschens - eine Einführung. in: Defila, R. Di Giulio, A. (eds). 2018. Transdisziplinär und transformativ forschen. Eine Methodensammlung. Springer VS. 9-38.

(12) Arnold, A. Piontek, F. Zentrale Begriffe im Kontext der Reallaborforschung. in: Defila, R. Di Giulio, A. (eds). 2018. Transdisziplinär und transformativ forschen. Eine Methodensammlung. Springer VS. 143-155.

(13) Beecroft, R. et al. Reallabore als Rahmen transformativer und transdisziplinärer Forschung: Ziele und Designprinzipien. In: Defila, R. Di Giulio, A. (eds). 2018. Transdisziplinär und transformativ forschen. Eine Methodensammlung. Springer VS. 75-100.

(14) Ministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Kunst Baden-Württemberg. Baden-Württemberg fördert Reallabore. Available at https://mwk.baden-wuerttemberg.de/de/forschung/forschungspolitik/wissenschaft-fuer-nachhaltigkeit/reallabore/

Further Information

- The EnoLL (European Network of Living Labs) connects, lists and supports hundreds of Living Lab projects in mostly Europe, but also internationally.

- A good overview on projects, literature and actors for Real-World Laboratories for sustainability can be found on https://www.reallabor-netzwerk.de/.

The author of this entry is Christopher Franz.