Difference between revisions of "Hermeneutics"

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

== Background == | == Background == | ||

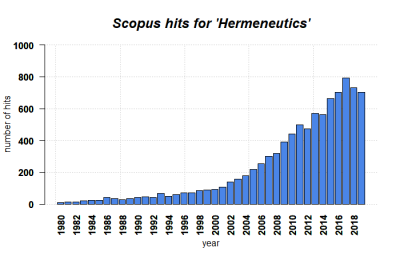

| − | [[File:Hermeneutics.png|400px|thumb|right|'''SCOPUS hits for Hermeneutics until 2019.''' Search term: 'hermeneutics' in Title, Abstract, Keywords. Source: own.]] | + | [[File:Hermeneutics.png|400px|thumb|right|'''SCOPUS hits per year for Hermeneutics until 2019.''' Search term: 'hermeneutics' in Title, Abstract, Keywords. Source: own.]] |

The roots of Hermeneutics reach back to antiquity. The word 'Hermeneutics' derives from the Greek word ''hermeneuein'', which basically means “to explain”. The messenger-god Hermes brought messages from the gods to the humans and explained their meaning to them (4). There has been a highly developed practice of interpretation in Greek antiquity, aiming at diverse interpretanda like oracles, dreams, myths, philosophical and poetical works, but also laws and contracts. The beginning of ancient Hermeneutics as a more systematic activity, however, goes back to the exegesis of the Homeric epics. | The roots of Hermeneutics reach back to antiquity. The word 'Hermeneutics' derives from the Greek word ''hermeneuein'', which basically means “to explain”. The messenger-god Hermes brought messages from the gods to the humans and explained their meaning to them (4). There has been a highly developed practice of interpretation in Greek antiquity, aiming at diverse interpretanda like oracles, dreams, myths, philosophical and poetical works, but also laws and contracts. The beginning of ancient Hermeneutics as a more systematic activity, however, goes back to the exegesis of the Homeric epics. | ||

Revision as of 10:40, 9 November 2020

| Method categorization | ||

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Qualitative | |

| Inductive | Deductive | |

| Individual | System | Global |

| Past | Present | Future |

Annotation: Hermeneutics describes two things: first, a scientific method that will be described in this entry. Second, a branch of philosophy that revolves around the ontological question of how to understand not only texts and symbols, but life in general. It is a field that deals with the characteristics of knowledge. For more information see sources (1) and (2) in the References.

Background

The roots of Hermeneutics reach back to antiquity. The word 'Hermeneutics' derives from the Greek word hermeneuein, which basically means “to explain”. The messenger-god Hermes brought messages from the gods to the humans and explained their meaning to them (4). There has been a highly developed practice of interpretation in Greek antiquity, aiming at diverse interpretanda like oracles, dreams, myths, philosophical and poetical works, but also laws and contracts. The beginning of ancient Hermeneutics as a more systematic activity, however, goes back to the exegesis of the Homeric epics.

Hermeneutics was further developed in the Middle Ages: "In its earliest modern forms, hermeneutics developed primarily as a discipline for the analysis of biblical texts. It represented a body of accepted principles and practices for interpreting an author's intended (and inspired) meaning, as well as providing the proper means of investigating a text's socio-historical context." (5). Then, "Hermeneutics took on a new and widening importance in the early modern period with the application of philological techniques for the validation and authentication of classical texts. With the Reformation, hermeneutic approaches were further deployed in intense exegetial exercises devoted to the resolution of contested meanings in scriptural texts." (4) The ambition of early modern hermeneuts was to assign correct meanings to a text and generate 'truth'. These aspects remained the focus of Hermeneutics until the period of Enlightenment.

During the last decades and centuries, Hermeneutics has emerged into a field of philosophy, whereas its origins lie rather in a methodological approach. "It has recently emerged as a central topic in the philosophy of the social sciences, the philosophy of art and language and in literary criticism - even though its modern origin points back to the early ninteenth century." (2) As a method, Hermeneutics is nowadays mostly used in the Social Sciences and Humanities, including theology, law, psychology, philosophy and history, with diverging methodological characteristics.

Key Figures

Schleiermacher, Friedrich Daniel Ernst (1768-1834): After finishing his studies in theology, philosophy and philology, Schleiermacher worked as a private teacher, preacher, and later professor for theology. In Berlin he became friends with Friedrich Schlegel, he joined the academy of sciences and became its secretary of philosophy. Schleiermacher can be seen as the founder of methodological – also called systematic – Hermeneutics, the new branch that dropped the traditional view of texts as keepers and producers of truth. He instead highlighted the importance of differentiating between grammatical and psychological interpretation.

Dilthey, Wilhelm (1833-1911): Dilthey lived from 1833 to 1911 and was a German philosopher. He took up the theory of the hermeneutic circle which was first mentioned by Schleiermacher and Friedrich Ast: Each individual part is revealed through the whole, and the whole through the individual. This points out that every fact, observation, or statement is always already connected to certain preconceptions. In Dilthey’s opinion this was true not only for humanities but also for the theories of natural sciences. Dilthey influenced many other famous philosophers such as Husserl, Heidegger, or Cassirer.

Heidegger, Martin (1889-1976): For Martin Heidegger, a German philosopher, hermeneutics is the existential basis of our human experience - according to him, being is itself shaped by understanding and interpretation. His philosophical concept of hermeneutics was and is important for the following theories and analyses.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg: Gadamer (1900-2002) was one of the most influential German philosophers of the 20th century. Highly influenced by Martin Heidegger, he turned away from Schleiermacher's and Dilthey's methodological hermeneutics. Instead, he had a universal approach to the topic of understanding meaning. Hermeneutics for him is not only a method but the basis of human existence. In his main work – Wahrheit und Methode (truth and method) – Gadamer points out that to interpret, one needs to be open, willing to reflect, and conscious of one's own prejudices and presumptions.

Habermas, Jürgen and Oevermann, Ulrich: The German philosopher and sociologist Habermas criticizes Gadamer’s universial view on hermeneutics. Oevermann, who is a German sociologist, used to be an assistant of Habermas at the Frankfurt School. He coined the term Objective Hermeneutics, a method that is predominantly used in social sciences and sociology.

What the method does

Hermeneutics as a method "(...) offers a toolbox for efficiently treating problems of the interpretation of human actions, texts and other meaningful material." (1). It helps with making sense of the relationship between an author, his text, and the reader. Depending on the various theorists, the major goal of interpretation is either decoding and understanding the author's intention at the time of writing, understanding a text only through itself, or through the social and cultural context (1). Generally speaking, Hermeneutics aims at having a clear distinction between interpretation as an activity directed at the meaning of a text and textual criticism as an activity that is concerned with the significance of a text with respect to different values (1) (Meaning is what is represented by a text or what the author meant by his use of a particular sign sequence. Significance names a relationship between that meaning and a person, a conception, or situation.)

As the information on key figures show, there are many different approaches to using Hermeneutics as a method. However, here are some steps and principles you can follow if you choose a hermeneutic strategy to deal with texts. None of them are wrong, they just serve different purposes and are suitable for different questions, disciplines, or media:

The Hermeneutic Process

These three steps are a basic guideline of the hermeneutic process:

- elocutio (or understanding): the studying of the object of interpretation itself, e.g. the pre-given text

- interpretatio (or interpretation): the act of interpreting, analysing and understanding the given object

- explicatio (or explanation/judgment): the result of the interpretation or the text written by the interpretor as a result of the interpretation

According to Schleiermacher, a given text should be seen in perspective with the author's internal world. This method has been criticized and altered by later philosophers like Gadamer, who does not regard the author's intention to be a critical point in the interpretation process. However, the principle of psychological interpretation is still a very important step in historical disciplines for example, where understanding the author's/creator's intention is crucial to evaluate the significance of a source or object. Consequently, one may distinguish between two steps in the hermeneutic interpretative process:

- Grammatical interpretation (objective): This is the first step of interpretation according to Schleiermacher. Grammatical interpretation is all about understanding the relations between words and the sentences they appear in, sentences and paragraphs, paragraphs and chapters and finally their relation to the whole text. This is important, because "(...) the meaning of a complex expression is supposed to be fully determined by its structure and the meanings of its constituents". (1)

- Psychological interpretation (subjective): The second step asks you to interpret the text as a part of the author's internal world or soul. it reveals the author's subjective intention as well as his thoughts and feelings towards the subject. The historical, societal, cultural, political and religious background of an author influences the meaning of his work.

Objective Hermeneutics

The qualitative empirical research method of Objective Hermeneutics was introduced by Ulrich Oevermann. It is currently one the most prominent approaches in qualitative research in German-speaking countries (6). Objective hermeneutics, in contrast to conventional hermeneutics, tries to work out not only the psychologically unconscious, but above all the socially unconscious in language. In this context Oevermann speaks of "latent social structures of meaning". In the objective-hermeneutic interpretation the interpreter compares the extent to which his own expectations of a linguistic interaction, based on everyday communication structures, apply or differ from those presented in the text or interview.

|}

Here are five of the core principles or rules of Objective Hermeneutics (7):

- Context-freedom: The initial interpretation of a text should not be influenced by its context. The interpretor should create his own contextual image based on the text only and can compare this image with the context afterwards and then reevaluate it.

- Literality: The text speaks for itself and should not be judged at first (e.g. do not judge spelling or grammar mistakes as 'wrong' - they might have been made consciously to convey a specific message).

- Sequentiality: A text should be analysed chronologically without skipping passages or jumping back and forth between chapters.

- Extensivity: The extensivity principle makes clear that every little detail of a text must be included in the interpretation, no matter how irrelevant it seems.

- Frugality: This requires the interpreter to only create readings that are enforced by the text and, accordingly, to only allow case structure hypotheses that can be proven using the text.

The Hermeneutic Circle

The term "Hermeneutic Circle" was coined by Friedrich Ast, Wilhelm Dilthey and Georg Gadamer and is one of the key terms of Hermeneutics. The principle means that a whole text can only be understood if you understand its individual parts, while the individual parts can only be understood if you understand the whole. This shapes the process of interpretation into a circular structure. The theory of the Hermeneutic Circle identifies three stages and one preliminary stage (8):

- Preliminary stage: development of a pre-understanding, mastery of the language, idea of the external conditions of a text

- The hermeneutical draft (first stage): The horizon of understanding and the horizon of meaning merge

- The hermeneutic experience (second stage): pre-understanding is expanded and corrected

- The improved draft (third stage): deeper understanding, maturation of the prior understanding

With this revised pre-understanding, the process of understanding can be restarted so that the previous stages are run through again. In principle, this circle can be repeated endlessly. Other theories choose the term "hermeneutic spiral" instead or reject the concept altogether.

Strengths & Challenges

- The different hermeneutic approaches and principles can be applied to studies in almost all disciplines - especially all Humanities, Social and Natural sciences - which makes it a universial method of understanding.

- By trying to understand the meaning of an object, as well as the intention behind its creation, one is able to get a deeper understanding of the relations between the author as a person, the text and its historical/cultural/social background, and the reader with his or her own background.

- There are so many different approaches and opinions on hermeneutic methodology that it can be difficult to stay on top of things.

- One aspect of Hermeneutics that is still widely debated is the question which element should be emphasized: The author' intention, the cultural-historical context of the text or the reader's culturally conditioned way of understanding the text. This can create an imbalance or incomplete interpretation (5).

- A central challenge to most forms of Hermeneutics is the subjectivity of the interpreter. As Gadamer proposes, it is crucial that the interpreter is conscious of his own prejudices and expectations before studying a text.

- It has been a challenge to determine - assuming that authorial intention is the goal of interpretation - factors that can track or measure this intention.

Key Publications

- Aristotle (1938). On Interpretation. Harold P. Cooke (trans.). In Aristotle, Vol. 1 (Loeb Classical Library). William Heinemann, p. 111–179.

- Gadamer, H.-G. (2013). Truth and Method. Bloomsbury.

- Gadamer, H.-G. (1975). "Hermeneutics and Social Science". Cultural Hermeneutics. 2 (4). p.307–316.

- Heidegger, M. (1962) [1927]. Being and Time. Harper and Row.

- Oevermann, U. et al. (1987). Structures of meaning and objective Hermeneutics. In: Meha, V. et al. (eds.). Modern German Sociology. European Perspectives: a Series in Social Thought and Cultural Criticism. Columbia University Press, p. 436–447.

- Seebohm, T. (2007). Hermeneutics: Method and Methodology. Springer.

- Zimmermann, J. (2015). Hermeneutics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

References

(1) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2016. *Hermeneutics.* Last accessed on 15.07.2020. Available at [1]

(2) Bleicher, Josef (2017): Contemporary Hermeneutics: Hermeneutics as Method, Philosophy and Critique. Routledge.

(3) Seebohm, Thomas (2004): Hermeneutics. Method and Methodology. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

(4) Gardner, Philip (2010): Hermeneutics, History and Memory. Routledge.

(5) Porter, Stanley; Robinson, Jason (2011): Hermeneutics. An Introduction to Interpretive Theory. Eerdmans Publishing.

(6) Reichertz, Jo (2000): Objective Hermeneutics and Hermeneutic Sociology of Knowledge. In: Flick, Uwe et

al. (Eds.). Companion to Qualitative Research. Sage. Summary available at [2]

(7) Wernet, Andreas (2000): Einführung in die Interpretationstechnik der Objektiven Hermeneutik. Leske + Budrich.

(8) Gadamer, Hans-Georg (2013). Truth and Method, Bloomsbury.

The author of this entry is Katharina Kirn.